To accompany Charters Wynn’s story about US aid to the USSR during World War II, we offer this video of Lend-Lease in action.The narration is translated below.

“On the evening of June 24, 1941, Prime Minister of Great Britain Winston Churchill came on the radio. He declared: “Any person belonging to a country fighting against fascism will receive British aid.” He went on to say that he will give Russia and its people all the help that the British government can offer. On October 2, 1941, the agreement was signed. Under the terms of the agreement, Great Britain and the United States pledged to dispense aid to the Soviet Union beginning on October 1, 1941 until the end of June 1942 by providing approximately 400 airplanes, 500 tanks, rockets, tin, aluminum, lead, and other wartime materials. It was declared that Great Britain and the United States will help mobilize and deliver these materials to the Soviet Union.

Hitler spared Murmansk. He expected to capture it quickly in order to use it for its port system, repair and maintenance factories, and docks. Murmansk was the only port in Northern Russia that did not freeze in the winter. Its direct access to Moscow by rail lent it even more geostrategic value. However, Hitler’s army hit an impasse approximately 80 kilometers from Murmansk. Successful naval operations implemented by the Russian military further ruined the Fuhrer’s plans to capture the city by land, leading him to issue an order to destroy the city from above. Consequently, Murmansk endured the longest bombing campaign in the history of the Second World War.”

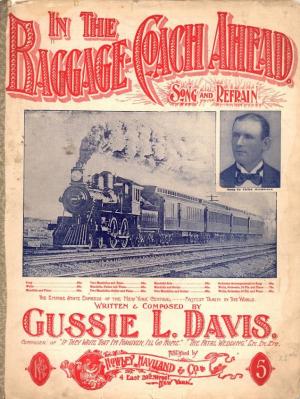

The song was the most popular composition of

The song was the most popular composition of  In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with

In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with