By Caroline Murray

Los Angeles is a city famous for its Hollywood celebrities and traffic, but a new project reveals an often overlooked part of the city’s past and present: its indigenous population, cited as one of the largest among American cities. Mapping Indigenous LA (MILA) brings to life the histories and current dilemmas of LA’s indigenous people in the twenty-first century, instead of leaving them behind in the past.

MILA combats the perception that these communities have disappeared over decades of assimilation and urban growth and exist only in a colonial context. The project disrupts the traditional, chronological narrative of history with its growing number of story maps, each featuring a place or issue of significance for LA’s indigenous groups. The maps contain videos, documents, book recommendations, and other archives that record native histories to give new meaning to locations in LA.

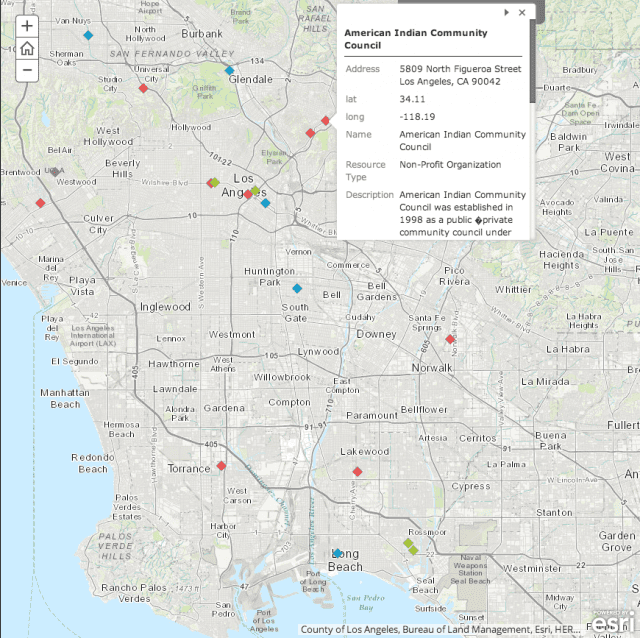

Map of Indian Resources (via MILA).

As MILA digs deeper, beyond the traditional idea of a map, it also works to expand the meaning of indigeneity by including stories not only from the native Tongva, but also other American Indians, Pacific Islanders, and citizens of Latin American indigenous diasporas who migrated to LA. You can explore the native village and springs of Kuruvungna, read about Latin American indigenous festivals, and listen to Tongva Elders reflect on their people’s displacement. You can view modern locations of Indian healthcare and education resources in LA, which many indigenous people struggle to find. MILA doesn’t allow its maps to provide only one definition or narrative; instead, they offer intricate, multifaceted histories that reflect the diversity of LA’s indigenous communities.

Historic landmark sign marking the location of Serra Springs, called Kuruvungna by the native Gabrieleno Tongva people. The springs were a natural fresh water source for the Tongva people (via Wikimedia Commons).

The American Indian Education story map perhaps best demonstrates all of MILA’s goals. Multiple perspectives color the stories and share different sides of indigenous communities’ complex relationship with American education systems. The pain inflicted by Indian schools, the worry over the loss of native languages, and the hope new cultural programs are bringing to LA can all be felt while exploring the map.

The maps not only create awareness among non-indigenous people; they almost more importantly provide a digital network for indigenous groups to learn from and relate to each other in ways they might not have before. MILA wishes to add more maps and encourages people to create their own to foster connection between different communities. While the subjects and perspectives in the maps vary, they all communicate a common message from indigenous groups in LA: We are here, and we will be heard.

![]()

You may also like:

Cameron McCoy recommends L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present by Josh Sides (2003).

Erika Bsumek explores several titles related to Navajo Arts and the History of the U.S. West.

Nakia Paker reviews Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South, by Barbara Krauthamer (2013).

![]()