Martin Nesvig’s newest book, The Women Who Threw Corn, offers a novel approach to the cultural view and development of sorcery and magical practices in sixteenth-century Mexico, as seen through the lens of acculturation, or cultural assimilation between groups. This is the first book in an upcoming two-part series called Xolotl Rite, and whereas this book highlights women, the second will focus on the acculturation of non-Indigenous men. Organized into three parts, “Witches and their Enemies in the Early Modern World,” “Magic in the 1520s and 1530s,” and “The Cultural Hybrid Healer-Witch,” the book’s structure enables readers to engage directly with whichever section most interests them. Through a detailed analysis of previously unexamined magic-related investigations (p. 153), Nesvig demonstrates that the acculturation of the non-Indigenous population to Nahua culture occurred more quickly and at an earlier stage than earlier scholarship has suggested.

Using a methodology of “reverse ethnohistory,” he inverts the traditional historiography of studying Indigenous responses to Spanish customs and their imposition through colonialism, instead looking into how non-Indigenous women adapted healing and spiritual concepts taken from Nahua culture. In this way, he flips the focus of “histories of discovery, women, witchcraft, the Inquisition, and the social history of settler-colonialists” (p. 20).

The first three chapters comprise Part I, which examines the “legal, theological, and cosmological ideas about magic and sorcery in both Spain and Mexico” (p. 25). The primary methodology here is a linguistic analysis, analyzing how certain terms relating to magic were translated both into Spanish and into Nahuatl and how false equivalencies were established between the Spanish “witch” and the Nahua “nahuallis,” how the Spanish “sorcery” became the Nahua “tlaphohualiztli.” The following section analyzes early sorcery trials and investigations in Mexico City, unpacking how the women on trial rapidly acculturated themselves to Nahua ideas of magic across class and ethnic boundaries. Part III rounds out the narrative by exiting the geographical scope of Mexico City and extending the time frame to the latter half of the sixteenth century. In this part especially, Nesvig investigates the more physical and visual aspects of magic, such as tattooing, the evil eye, and the use of peyote and patle. By the end of the book, Nesvig recounts a story of a non-Indigenous woman using Mesoamerican forms of magic without the use of a Nahua intermediary, demonstrating a far greater extent of acculturation for the time period than has previously been understood.

The deep and complex analysis of previously unexplored sorcery investigations makes Part II the highlight of the book. Here, Nesvig pays particular attention to the variety of ways that different populations in colonial Mexico City incorporated Nahua ideas of magic based on their own cultural background. For example, Nesvig demonstrates that Spanish women adopted Mesoamerican iconography, powders, roots, and yerbas to conduct love magic and the Nahua language to conduct spells, and Indigenous healing rites. On the other hand, women of African descent utilized freedom magic that drew upon Nahua materiality, while the Spanish witches did not. Nesvig also sheds light on the unequal ways that the courts treated Spanish and African women on trial for witchcraft. Finally, Canarian, Morisca, and North African women, who were seen as oversexed, understood the stereotypes associated with their ethnicities and used sex and love magics as survival strategies. Nesvig argues that their own liminal position in Spanish society allowed them to quickly adapt and acculturate to Mesoamerican forms of magic. Each of the case studies analyzed across the chapters helps Nesvig demonstrate that the process of acculturation in the capital city was both immediate and rapid among women from many different ethnicities and social classes.

Flowers, incense burners and perfumes. Florentine Codex. Source: Wikimedia Commons

One area of potential confusion lies in the text’s near-synonymous use of the terms “witch” and “sorcerer.” In Inquisition historiography, scholars typically emphasize that Spanish authorities distinguished between the two: witches were those who entered into an explicit pact with the devil, while sorcerers practiced magic without such a pact. Nesvig acknowledges this distinction, yet often employs the two terms interchangeably, which at first can appear imprecise. On closer reading, however, this choice proves consistent with his broader aims. Because Nesvig approaches magic-related practices primarily through an Indigenous lens, retaining the Spanish-imposed differentiation would have distorted that perspective. The Nahua themselves likely would not have marked such a rigid boundary between witchcraft and sorcery, and the fluidity of Nesvig’s terminology reflects this. Whether entirely intentional or not, the effect is to demonstrate how non-Indigenous women engaged with and absorbed Nahua understandings of magic, for which the Spanish categories would have been ill-suited.

Another point of confusion is Nesvig’s use of the term “cultural syncretism,” or the merging and blending of multiple cultures, as a factor in the process of acculturation. While Nesvig does not fall into the most serious critique of “syncretism,” it is still important to be aware of how its use might impact the work. The framework of syncretism has been heavily contested, especially among scholars of religious studies, mostly due to its connotations indicating that each of the cultures in the melding process could be distilled to a “pure” version that existed before their contact. However, especially when looking at religion and spiritual beliefs, cultures are continually changing due to both internal and external factors, and the idea of a “pure” version of a culture is reductive. Therefore, while Nesvig’s framework of acculturation is convincing and helps develop his argument, his use of cultural syncretism to demonstrate it is something that must be carefully unpacked so as to not fall into the term’s contested history.

The tamal and tortilla seller. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Despite this minor point of contention, The Women Who Threw Corn is a fascinating and accessible read for anyone interested in the history of magic, European-American contact, or histories of gender. Seen primarily through the evolution of magic practices in New Spain in the sixteenth century, Nesvig demonstrates how non-Indigenous women utilized Nahua words, materials, and spiritual iconography in the creation of their spells. Beyond this, the methodology of a reverse ethnohistory is intriguing, and can be useful for future histories of Indigenous and non-Indigenous contacts. If The Women Who Threw Corn is any indication, the second book in the Xolotl Rite series promises to be equally impressive.

Chloe Foor is a Phd student in History at the University of Texas at Austin. Her current project focuses on how physical spaces impacted gendered, racial, and religious identities in the New Kingdom of Granada in the seventeenth century, as well as how historical actors manipulated those identities to claim space for themselves. Currently, she is working with the JapanLab/History Games Initiative to develop a video game highlighting Cartagena Inquisition’s witchcraft trials during the early seventeenth century.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

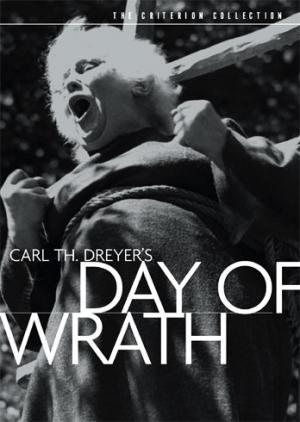

Dreyer, who is best known for

Dreyer, who is best known for