Originally posted on Christopher Rose’s blog on April 12, 2018.

I know, not the best title for my first blog entry, right?

A couple of months back, I presented some of initial findings on epidemic and epizootic disease in Egypt during the first World War at a symposium. (Ok, I’ll tell you the symposium was at Oxford. Yes, you may touch me.) I was flattered to be asked, especially since, as an ABD candidate, I got to be part of a two-panel session with speakers like Khaled Fahmy and Marilyn Booth (I’m still not entirely convinced I didn’t embarrass myself and everyone else, but that’s impostor syndrome for you).

The paper–which you can read here–is a short synopsis of human suffering during the war, especially among the poor, rural classes in Egypt, which are largely undocumented. It’s a works-in-progress presentation, very much based in preliminary findings, as one does at this stage in writing.

My dissertation focuses on breakdowns in public health during the war–the topic sentence could be summed up as “1918 was a deadly year for the Egyptian populace.” Even if one heeds Roger Cooter’s warning about reifying a positivist relationship between war and disease[1] –and I’ve compiled statistics for nearly a decade before and after the war–the demographic anomalies in Egypt between 1914 and 1918 are unmistakable. Four times as many Egyptians died of disease during the war than from military actions.

1918 also saw the birth rate decline to its lowest rate in a quarter century.

I described a number of issues: food shortages that were documented as early as 1916. As residents complained about shortages of soap, eggs, cheese, and meat the Anglo-Egyptian administration, concerned with keeping the protectorate profitable, maintained a positive trade balance, exporting goods that were dearly needed at home. The cost of some basic household items rose over 200% between 1914 and 1918.

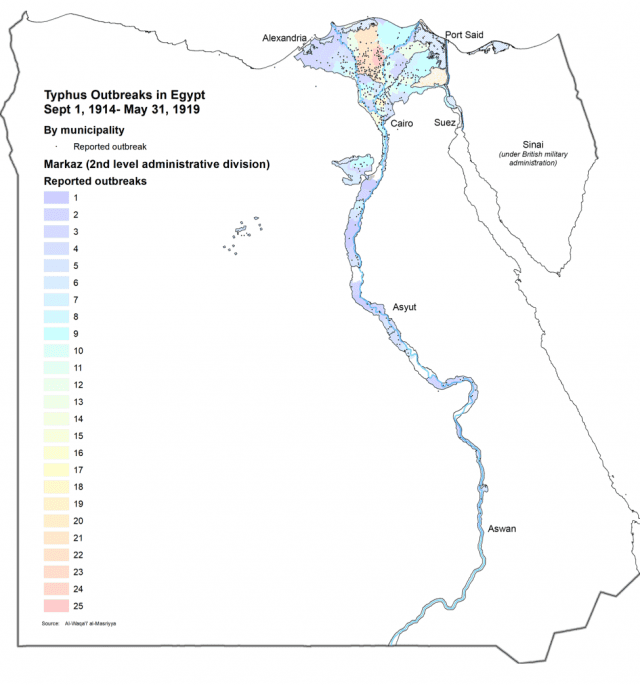

Likewise, relapsing fever and typhus cases increased substantially — both are louse-borne diseases, which can likely be tied to the increased movement of troops and support staff (including the men of the Egyptian Labour Corps). The war ended with the “Spanish flu” outbreak, which killed almost 140,000 Egyptians in just under three months.

There were also epizootics of both cattle plague (rinderpest) and foot-and-mouth disease that lasted over 18 months in large swaths of the country. Is there a relation between this and the soaring price of meat? It’s almost certainly the source of much of the protein that was sold on the black market in major cities.

As I said. Cheerful stuff.

During the break that followed my panel, a member of the audience approached me, identifying himself as a member of the landholding class from the Sharqiyya province in the Nile Delta (for the record, he is not an academic).

He insisted that I was completely wrong about nearly everything that I had said.

“We had hygiene!” he declared. “People didn’t die from these diseases in the 20th century!”

He suggested that I extend the dates of my study by decades in each direction; for example, he inquired if I had I looked at the number of deaths incurred through the construction work on the Suez Canal (1863-69), or knew how many more people died of disease in Egypt in the 18th century.

I won’t lie. This was my first outing with this material, and this was … not the sort of feedback I had hoped to get. The more I tried to explain the nuance of my argument, the more pushback I got. Having spent 3 months mapping the country from cataract to Delta, I tried to change the subject and ask where he was from–meaning where, specifically, in Sharqiyya. He looked at me as if I might just be the stupidest man on earth and responded, “Egypt?!”

Map showing typhus outbreaks in Egypt, September 1, 1914 – May 31, 1919 (created by Chris Rose, featured in the blog Mapping & Microbes)

As you can tell, I’ve let this episode roll right off my back.

However, I think there is something significant in the greater picture about his defensiveness, one that pushed me to think about the puzzling collective silence in nearly every history book about what I’m looking at. Even the Spanish flu is described in only two medical reports from the time; I’ve seen it mentioned nowhere else.

The notion of Egyptians dying in elevated numbers from disease was clearly distasteful to him–largely, I suspect, for the reason that it was undignified. People—at least not those of his class—did not die from disease in high numbers in the early 20th century.

In short, Egypt was modern. If it had not ascended, as the Khedive Ismāᶜīl had optimistically pronounced in 1869, to being among the ranks of countries which should be considered European, it had developed more rapidly than much of the Arab east, which languished in such a state that one scholar discussing the “Spanish flu” influenza pandemic in the Arabian peninsula (1919) could legitimately wonder whether medical officials in central Arabia were capable of distinguishing the influenza apart from other diseases with similar symptoms, such as typhoid.[2]

Indeed, my interlocutor is correct about that hygiene and medical care had been introduced under Muhammad Ali Pasha in the mid-19th century as part of a national campaign to improve public health. This has been described by LaVerne Kuhnke and Hibba Abuguideri (although the project had peaked in the 1850s and all but vanished under British administration).[3]

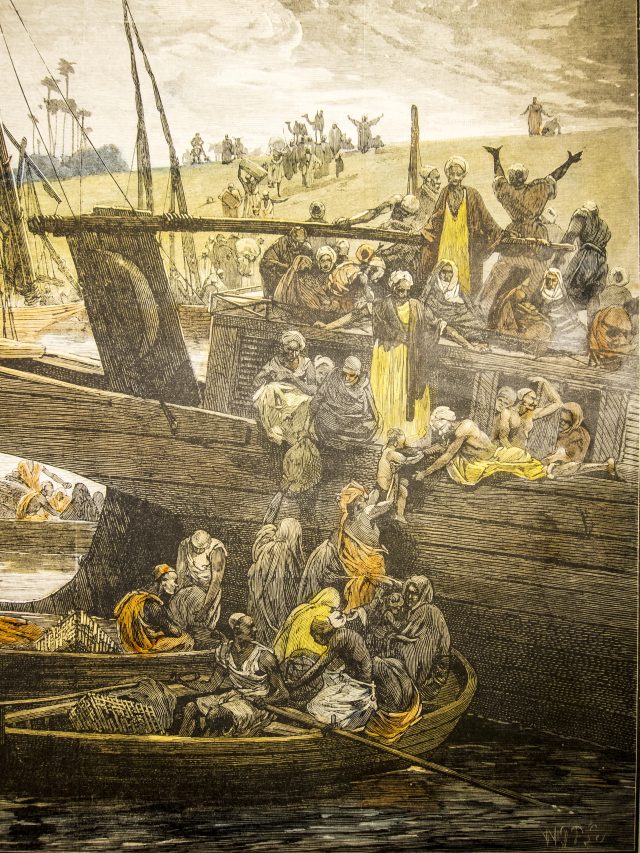

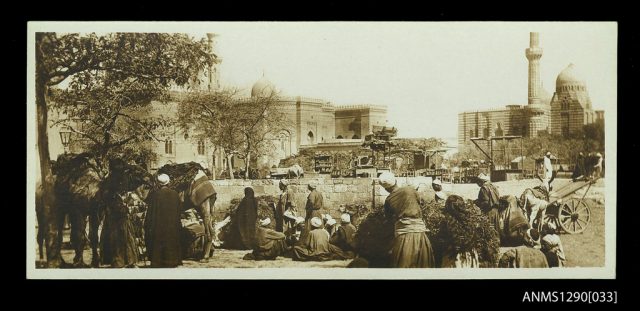

A market scene in Cairo during World War One (via Australian National Maritime Museum)

I struggled to explain in my response that afternoon that my interest was the significance of the war’s anomalous blip in the statistical record. The public health scheme in Egypt had, to a certain degree, brought epidemic disease under control, which is why the fact that infection and death rates soared during the war comprise a factor of interest. So, too, do the numbers of registered prostitutes in Egyptian cities, as well as the number of reported cases of venereal diseases, both of which increased substantially during the war and comprised their own crises in both medical and social health.

During the First World War, Egypt was a nation at war. Its citizens were recruited into the war effort, and many of those citizens faced bodily harm and death fighting for the Union Jack in far-off lands. Those who remained at home suffered from shortages of basic supplies–although production rates decreased slightly, they dropped nowhere near as much as consumption rates. They were forced to eat tainted meat that they purchased at high prices. They died of disease whose effects were exacerbated by malnutrition. Some turned to prostitution or other illicit activity to make ends meet.

There is nothing heroic about the fight against a virus, perhaps. As the First World War and the 1919 uprising became enmeshed together in the national historiographic project celebrating the nationalist movement and Egypt’s strive for self-determination, there was no space for sympathetic portrayal of poor women desperate to feed starving children and elderly relatives, and those who, in sheer desperation, turned to extreme measures to support themselves.

The commemorations held in Egypt from 2013 onward to celebrate the nation’s contribution to the First World War recognize only one of these groups.

I’m hoping to recognize the second.

[1] Roger Cooter. “Of War and Epidemics: Unnatural Couplings, Problematic Conceptions.” The Journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 16, no. 2 (2003): 283–302

[2] LaVerne Kuhnke. Lives at Risk. Vol. no. 24. Comparative Studies of Health Systems and Medical Care. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990; Hibba Abugideiri. Gender and the Making of Modern Medicine in Colonial Egypt. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013.

[3] Guido Steinberg. “The Commemoration of the ‘Spanish Flu’ of 1918-1919 in the Arab East.” In The First World War as Remembered in the Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, edited by Olaf Farschid, Manfred Kropp, and Stephan Dähne. Beiruter Texte Und Studien 99. Würzburg: Ergon-Verl, 2006, 159–60.

Also by Christopher Rose on Not Even Past:

Mapping & Microbes: The New Archive (No. 22)

Searching for Armenian Children in Turkey

Exploring the Silk Route

Review: The Ottoman Age of Exploration (2010) by Giancarlo Casale

What’s Missing from Argo (2012)

You may also like:

Charalampos Minasidis reviews Yugoslavia in the Shadow of War: Veterans and the Limits of State Building, 1903-1945 by John Paul Newman (2015)

Book recommendations compiled for the centenary of the outbreak of WWI