Fifty-one years ago this month, a momentous political event began in the South American country of Chile. For the first time in the Americas, and arguably the world, voters went to the ballot box and elected a government that was committed to forging a democratic path toward socialism.

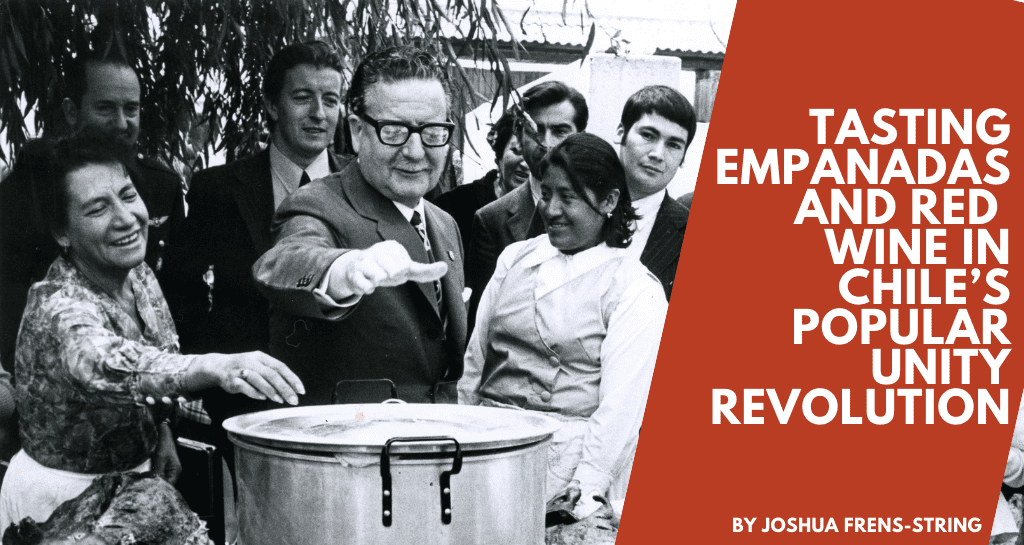

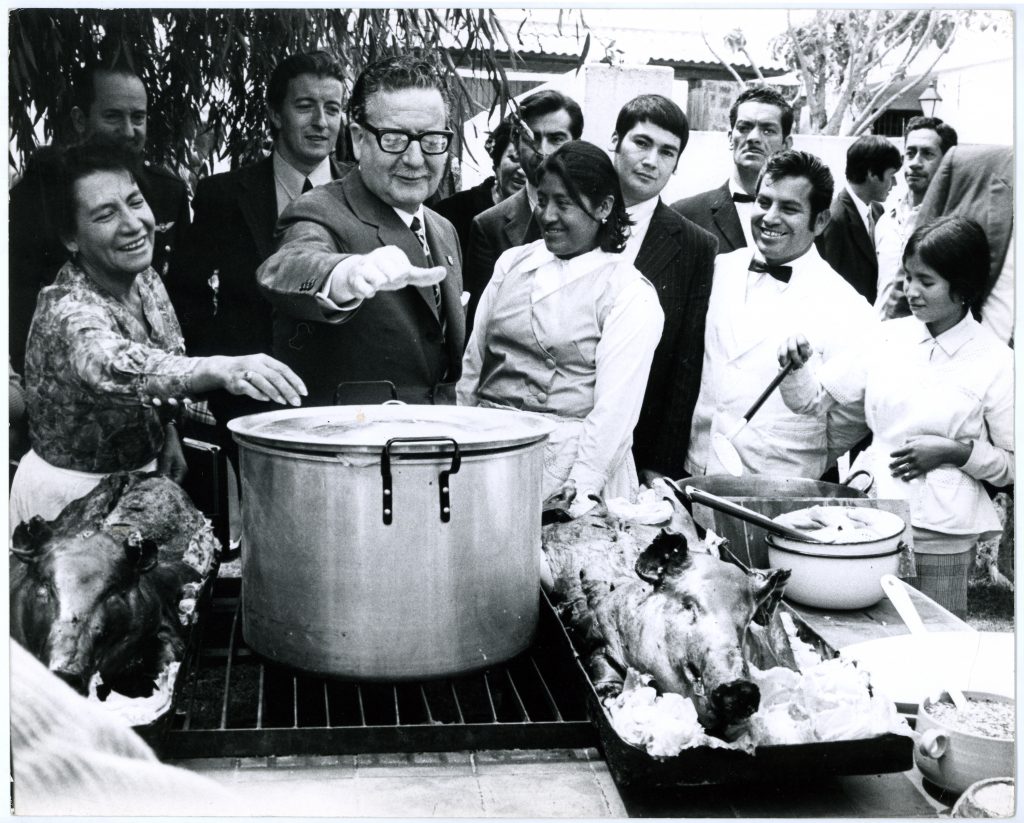

The Popular Unity (UP) coalition was comprised of Chile’s Socialist Party, Communist Party, progressive Catholics, and handful of other reform-minded movements. A bespectacled socialist named Salvador Allende led the broad-front coalition. A medical doctor by training, Allende was a familiar face to most Chileans. In the late 1930s, he had served as the country’s Minister of Health. He remained active in national political life as an elected member of its national legislature for most of the interceding three decades. In fact, Allende’s 1970 presidential bid was the socialist’s third such campaign, having run unsuccessfully multiple times before.

But 1970 proved to be different. This time Allende promised that Chile would chart a path between the narrow straits of the global Cold War that divided the U.S., on one side, and the Soviet Union (as well as the USSR’s close ally in Latin America, Cuba), on the other. In describing the unique national character of their political project, as well as the material benefits that would accrue to the most marginalized in Chilean society as a result, Allende and his coalition maintained from the start that Chile’s revolution would have the “flavor of empanadas (meat hand pies) and red wine.”

Almost a decade ago, when I began research for my new book, Hungry for Revolution: The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile (University of California Press, 2021), this slogan about the taste of empanadas and red wine immediately captured my attention. Beyond a few passing mentions of the mantra in political accounts of the UP era, I was struck by how few scholars had explored how and why these two quintessentially “Chilean” culinary items had come to stand in for the supposedly distinctive goals and nature of Allende’s democratic road to socialism.

That initial query would lead me on an archival journey through more than a half-century of social, cultural, political, economic, scientific, agricultural, and urban history. Through an engagement with Chilean state economic records, a wide array of print media, medical bulletins and journals, land reform documentation, and more, I began to ask, how would a history of the UP experience (1970-1973) that was centered around food alter our understanding of Chile’s 1000-day revolution, as well as the history of Chilean popular politics and state formation throughout the twentieth century?

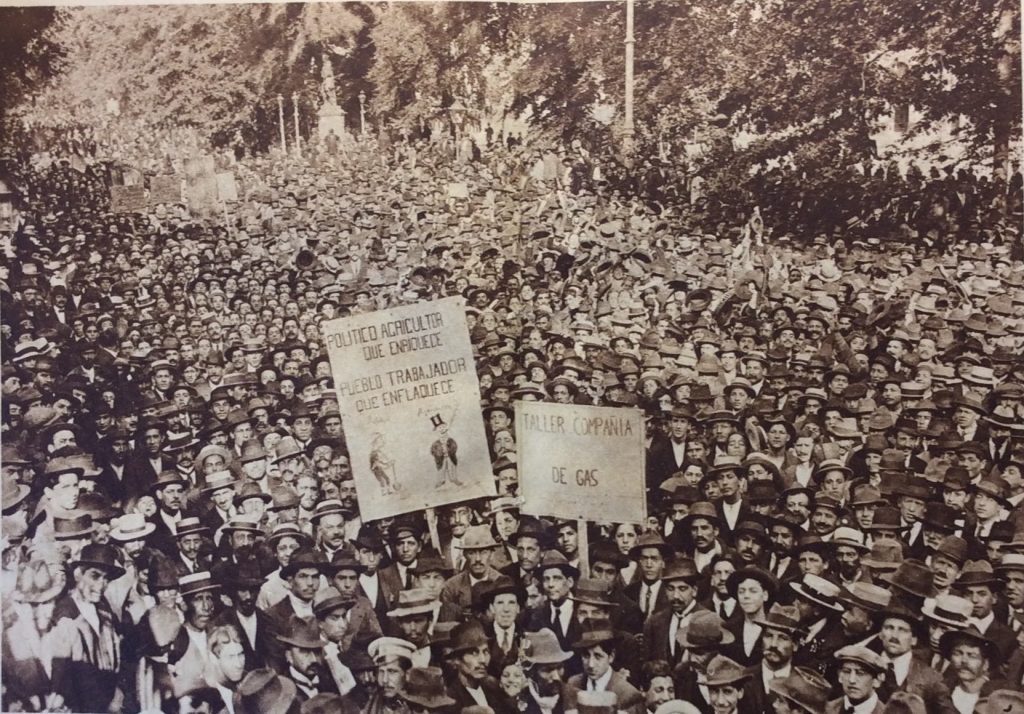

The research that eventually resulted in Hungry of Revolution became an attempt to reconstruct how decades of struggle over food fueled the rise, and eventual fall, of what was once one of Latin America’s most expansive social welfare states. Through a reconstruction of ties between workers, consumers, scientists, and the state, the book links two of the most significant storylines of twentieth-century Chilean history: the political fight of an increasingly organized urban working class to gain reliable access to cheap, nutrient-rich foodstuffs, on the one hand, and the struggle of the state (and to a certain extent rural peasants) to modernize Chile’s underproducing agricultural countryside, on the other.

By placing the history of food at the center of my research, I came to see that, across multiple decades, Chileans had sought to make food security a right of citizenship and a cornerstone of a more inclusive economic democracy. As a result, my research also revealed how one of the most pressing concerns in contemporary Chile—the problem of inequality—manifested and reproduced itself through the country’s system of food production, distribution, and consumption.

The book offers a reappraisal of some of the key social, political, and economic narratives in modern Chile history. For one, it challenges the common tendency to view food or consumer politics as a something that emerged as the Latin American social welfare or developmental state retreated in the face of an onslaught of market reforms in the late 1970s and 1980s. During that latter period, right-wing governments, many of them military dictatorships, violently suppressed left-wing parties and the labor movement. The dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet in Chile (1973-1990) was among the most infamous of these regimes. According to some scholars, it was during his rule that the consumer marketplace replaced mass politics and the shop floor as a site of permissible citizen political participation. The emblematic account of a modern consumer society during this era remains a 1988 book by the conservative Pinochet supporter Joaquín Lavín, entitled The Revolución Silenciosa (The Quiet Revolution). In the book, Lavín, who remains an important figure in Chilean conservative politics today, suggested that mass consumption was defining of a capitalist society’s success. But free-market forces needed to operate without government restraints if consumer well-being was to be ensured.

As I show in Hungry for Revolution, this articulation of consumption as a key metric of social and economic “health” or prosperity was not especially new to Chile under Pinochet’s reactionary regime. Rather, for almost the entire mid-twentieth century, consumption, particularly of basic food staples, was at the center of how everyday citizens and the political left understood the concept of citizenship and purpose of national economic development. This is a point that historians of Chile like Heidi Tinsman have articulated especially well. As other recent scholarship has demonstrated, the linking of consumption to what we might call social-democratic of even socialist political horizons extends to other parts of Latin America and beyond during this same period. The key difference, however, was that for much of the twentieth-century, progressive movements and social reformers agreed that the state had a critical role to play in promoting and protecting consumption. A strong state needed to tame the unfettered power of the open marketplace to guarantee access to what Latin American governments often referred to as “primary necessity goods.” To paraphrase what the US historian Meg Jacobs has written about the New Deal, as an interventionist state created consumer agencies and enacted new consumer regulations, many poor and working-class people across the Americas organized themselves to demand ever more robust forms of regulation, without which democratic participation in a nation’s social and economic life was seen as impossible.

Put simply, the politics surrounding food and other forms of basic consumption were central to progressive visions of economic and social democracy before consumer politics became a hallmark of a more market-based or neoliberal understanding of citizenship in the late 1970s and 1980s.

At the same time, by centering food in my historical analysis of twentieth-century Chile, something else even more interesting revealed itself: the struggle for cheap and abundant food became as much a fight over consumption as it became a site to build a different sort of food system – that is to say, a distinct architecture for determining what sort of food was produced in Chile (and how) and also to organize the channels through which that food was ultimately distributed. To the extent that the notion of economic equality was a central tenet of the twentieth-century Chilean left, social reformers’ fixation on resolving food-based inequities was paramount to achieving this goal.

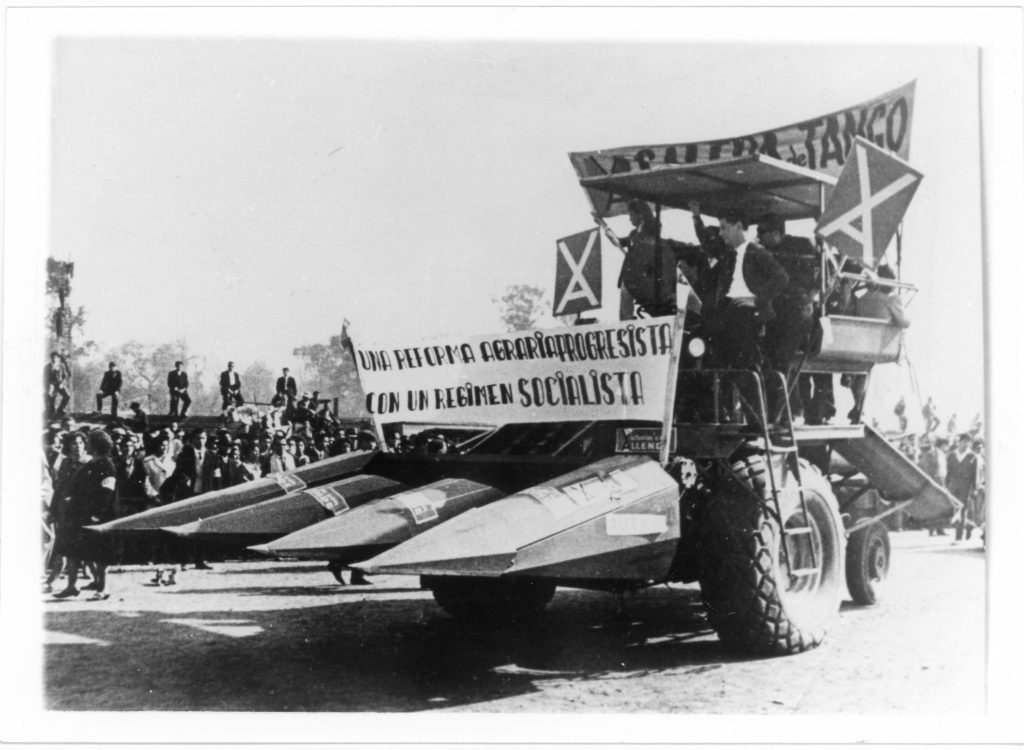

The project of agrarian reform (which I consider in detail in the fourth chapter of the book) was in many ways the axis around which visions of a more equitable food system turned in the middle of twentieth century. Between 1964 and 1973, the Chilean state broke up large agricultural estates and began redistributing those rural properties to landless peasants. At the same time, the state promoted the unionization of rural workers and offered technical assistance, cheap credit, and supplies to this new class of agricultural producers. While concerns about land tenure and rural working conditions helped drive agrarian reform in Chile, just as they did in many other parts of Latin America, Hungry for Revolution demonstrates that the content of agrarian production—and then the distribution of the new agricultural bounty that was produced on new land reform settlements—were also pressing national concerns during the 1960s and early 1970s. For example, by promoting the production of new sources of protein (such as chicken, pork, and even fish), food experts involved in agrarian reform sought to break Chile’s costly dependence on foreign imports of beef. And by planning agricultural development projects in areas that would streamline urban distribution efforts, those same agrarian experts and engineers sought to move Chile toward a position of greater national food self-sufficiency. The history of agrarian reform in Latin America, I contend, is very much a history of food.

The mobilization of food consumers and the state’s response to those mobilizations—whether through the enforcement of price controls, the creation of new food and nutrition agencies, or the promotion of agrarian reform—were defining features of Chile’s socialist landscape in the mid-twentieth century. But the quest for a society in which empanadas and red wine were abundant and accessible to all did not necessarily end in triumph. While the year 1971, the first year of the UP revolution, was one of unprecedented consumer bounty, the last year or two of the revolution were filled with intense social and economic challenges.

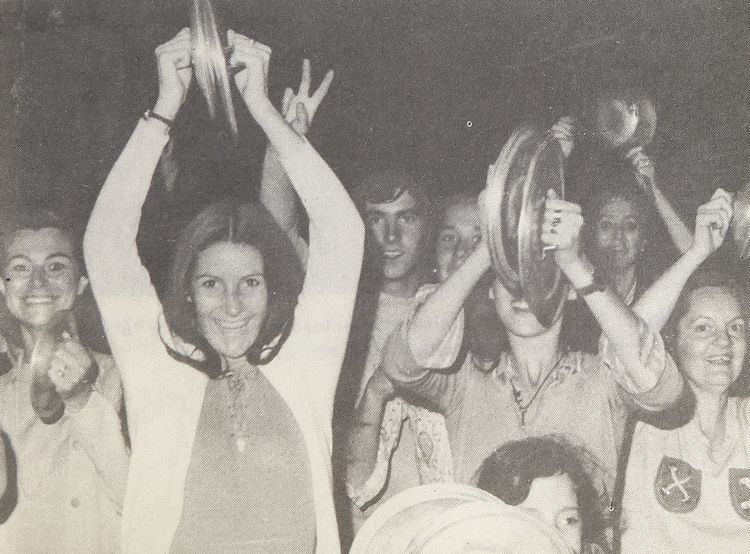

The return of food-based insecurity would become an issue that many Chileans associated with the UP government’s shortcomings. By continuing to advocate a vision of “proper” food consumption that was rooted in calculations of calories and vitamins, revolutionary leaders often minimized the social and cultural meaning that certain foods had to Chilean consumers. In presenting women as both the cause of decades of poor nutrition and the solution, the state reproduced a highly gendered notion of femininity that ultimately impeded women’s political action outside the household. And by too often emphasizing technical solutions to food production problems, agrarian experts did not do enough to tackle the deep-seated political power that Chile’s large landowner class continued to exercise in the early 1970s.

As a counterrevolution against the UP took hold in Chile, few images would become more iconic than those of middle and upper-class women banging empty cooking pots to demand the removal of Allende’s government from office or private food distributors parking their trucks alongside major highways to halt the distribution of essential consumer goods in the country. Such actions helped transform food into a market-based commodity, rather than a social and economic right of citizenship.

The history of food that I present in Hungry for Revolution is a story of how Chileans came to understand the everyday meaning of concepts like social welfare, economic justice, economic democracy, and citizenship in the twentieth century. But it is also a story about whose interests the Chilean state and economy, both past and present, have been set up to serve.

Joshua Frens-String is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin and an associate of the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies (LLILAS). He is the author of Hungry for Revolution: The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile (UC Press, 2021).

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.