If you cross the Colorado River at Redbud Trail and look upstream toward Tom Miller Dam, there amid the tumbled rocks you can still see the wreck of Austin’s dream. In 1890, the citizens of Austin voted overwhelmingly to put themselves deeply in debt to build a dam, in hopes that the prospect of cheap waterpower would lure industrialists who would line the riverbanks with cotton mills. Austin would become “the Lowell of the South,” and the sleepy center of government and education would be transformed into a bustling industrial city.

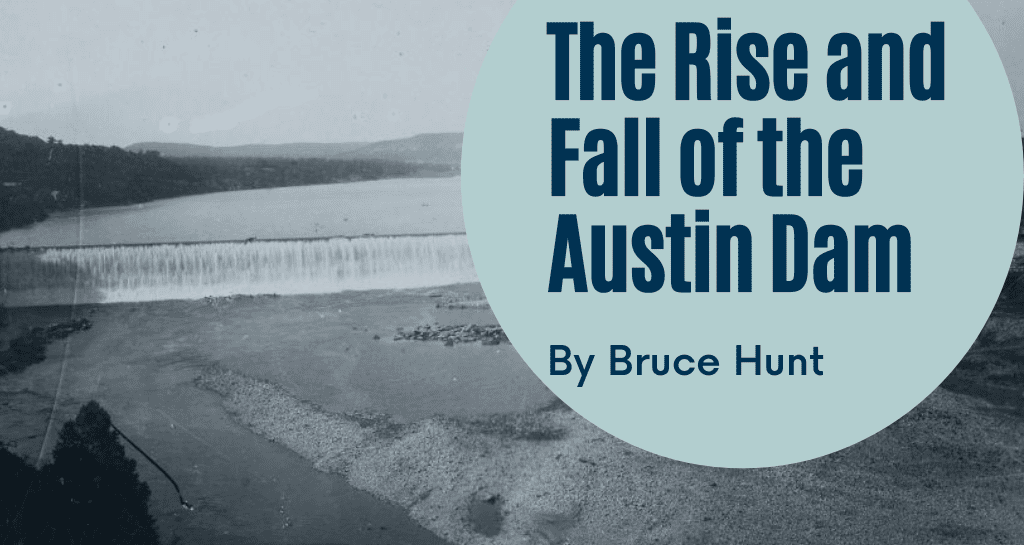

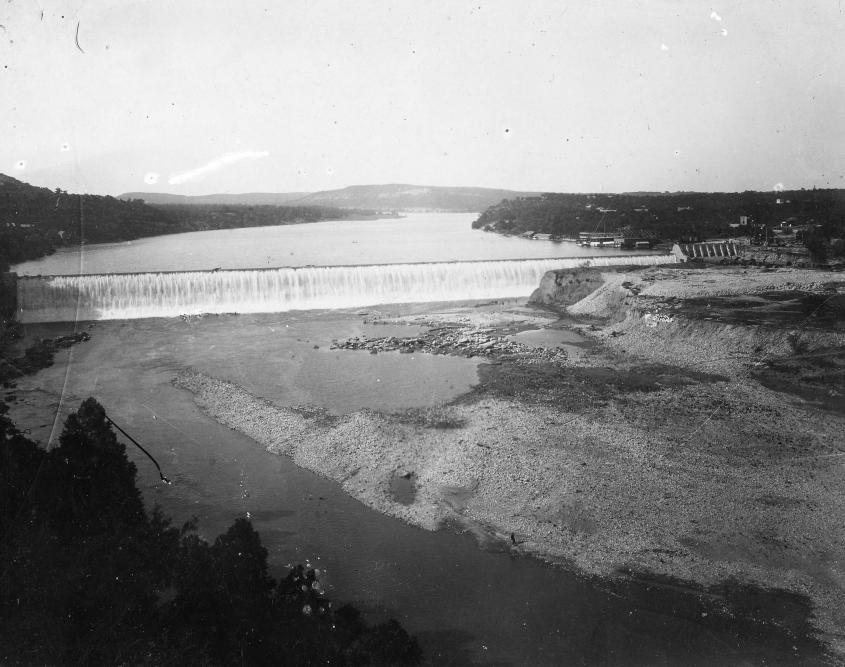

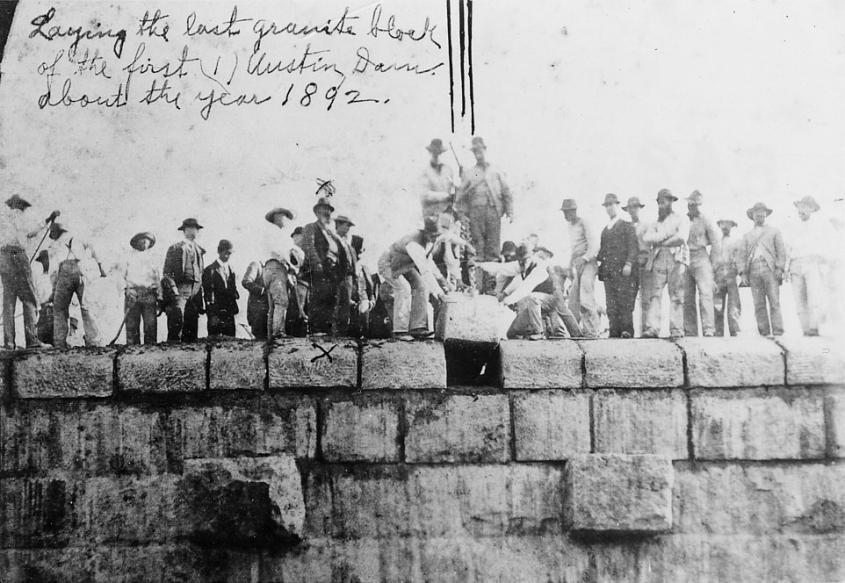

It never happened quite that way, of course. After strenuous efforts to sell enough bonds, and after several setbacks during construction, the city managed to complete the great granite dam in 1893 at a site just northwest of town. Standing sixty feet high and stretching nearly 1200 feet across the river, it was then one of the largest dams in the world. A. P. Wooldridge and other boosters of the project had originally envisioned harnessing the river to drive mill machinery directly, but the engineers they called in soon steered them toward the new technology of the day, and the powerhouse erected on the east bank of the river was filled with electrical dynamos that supplied current to Austin’s new network of electric streetcars, as well as to the “moonlight towers” the city acquired in 1895. The shores of the lake that formed behind the dam—named “Lake McDonald” for John McDonald, the mayor who had whipped up support for the project—attracted new residents and developers, while the waters of the lake itself drew those seeking respite from the Texas heat. Austin boomed in the mid-1890s, driven largely by land speculation. Monroe Shipe established “Hyde Park,” a classic “streetcar suburb” north of downtown, and smaller developments sprang up around the city.

One of the biggest land deals was engineered by San Antonio banker and businessman George Brackenridge, who had acquired a large tract of land just downstream from the proposed site of the dam, evidently hoping to sell mill sites once the dam was completed. But the promised cotton mills never materialized. The flow of the Colorado proved to be far more variable than the project’s promoters had claimed, and the dam was never able to produce the kind of steady power needed to drive a bank of mills. At times it barely sufficed to power the lights and streetcars.

Having never lived up to expectations, the dam failed spectacularly on 7 April 1900. Enormous storms upriver sent a torrent of water cascading eleven feet over the crest of the dam. After the rains had stopped, Austinites came out that bright Saturday morning to see their local version of Niagara. Then at 11:20 am they heard a loud crack—“like a gunshot,” several said—and watched in horror as a central section of the dam gave way and slid sixty feet downstream. Water blasted into the powerhouse, wrecking it and killing eight people. Lake McDonald vanished, and though the western end of the dam still stood, the eastern half was destroyed. More than a century later, great chunks of it are still to be found scattered in the riverbed, forming part of the present Red Bud Isles.

The Austin Dam was probably doomed from the start. Over the objections of their engineers, McDonald and other city leaders had chosen a singularly poor site to build a dam: the exact spot where the Balcones Fault Zone passes under the river. The rock on the eastern end of the site was so loose and fractured it could be shoveled up and water percolated freely through it, undermining the foundation of the dam. Nor had the dam been properly built. Joseph Frizell, the original engineer on the project, quit in disgust, complaining that McDonald had meddled with the design and let the contractor use inferior materials. Faced with such knavery, Frizell said, a responsible engineer had no choice but “to abandon the work as he would abandon fire and pestilence.” A string of other engineers quit the project, too, and the eventual collapse of the dam was in some ways not a surprise.

After 1900, the people of Austin did what they could to recover from the disaster. Having gotten a taste of city-owned electric power, they refused to go back; they bought out the local private power company, which used steam-driven generators, and today’s Austin Energy municipal utility is in a sense a legacy of the old Austin Dam. The city also tried to rebuild the dam itself, but a dispute with the contractor left the repairs unfinished in 1912, and another flood in 1915 damaged it further. By then Brackenridge had given up his hopes for industrial development, and in 1910 he donated his five hundred acres of riverside land to the University of Texas, which now uses it for student housing and a biological field laboratory.

The wrecked dam sat derelict, “a tombstone on the river,” until the Lower Colorado River Authority stepped in and, with federal money, rebuilt it as Tom Miller Dam, completed in 1940. The remaining portions of the 1893 and 1912 dams were incorporated into the new structure, but are now hidden under new layers of concrete. By the time it was finished, however, Tom Miller Dam was already overshadowed by the much larger LCRA dams built upstream at Lake Travis (Mansfield Dam) and Lake Buchanan (Buchanan Dam), which for the last seventy years have provided water, hydroelectric power, and flood control for Central Texas.

Most Austinites barely notice Tom Miller Dam today, and few know the story of the old Austin Dam at all. Over the years I’ve have several students write research papers and senior theses about the dam and its effects on Austin in the 1890s; one of the best, by Ed Sevcik, was published by the Southwestern Historical Quarterly in 1992 as “Selling the Austin Dam.” Ed emphasized how the story of the dam reflected an ongoing tension in Austin between proponents of development, eager to spend public money to try to attract private business, and those who see such urban bustle and industry as something to be avoided rather than embraced. It is a story that has not ended even yet.

Notes:

The Lower Colorado River Authority website has more historical material, including a large digital photographic archive.

Ed Sevcik, “Selling the Austin Dam: A Disastrous Experiment in Encouraging Growth,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly (96:2, Oct 1992)

Lauren Belfer, City of Light (2003). A novel, set in Buffalo in 1901, about building dams for electricity and the conflicts that came with industrialization, with a wide-ranging view of gender and class conflicts in that period.

Click here for Bruce Hunt’s previous article on Austin’s moonlight towers.

Photographs courtesy of the Lower Colorado River Authority

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.