When people think about fascism, two men come to mind: Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. However, as Robert Paxton shows in The Anatomy of Fascism, fascism was a practice that extended far beyond these two leaders. This is an original approach, as the majority of scholars focus on fascism as an ideology. Paxton instead examines fascism’s variations and focuses on fascists’ actions, and he compares them with other successful or unsuccessful versions of fascism. Paxton argues that fascism can be understood only through an examination at the local level. He builds his argument in stages by studying how these movements were created, how they were rooted in the political system, how they seized and exercised power, and if they were incorporated into the existing system.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

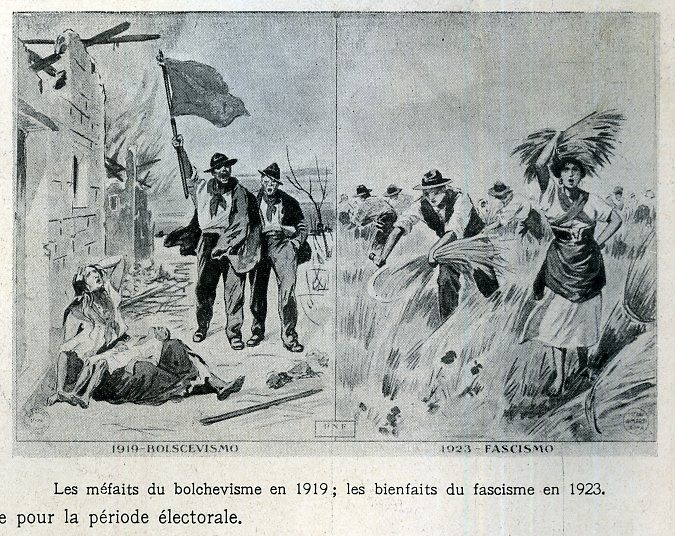

Paxton argues that fascism is not like other political movements. It is not supported by any coherent philosophical system but is a product of mass politics invented only after the introduction of universal suffrage, the spread of nationalism, and the entry of socialist parties into coalition governments. Coalition politics disenchanted many workers and intellectuals, while many politicians did not have the skills mass politics required. After the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the foundation of an anti-leftist movement that could adopt elements of the Left’s mass organization was necessary. The aftermath of the First World War and, later on, the Great Depression were critical for fascism’s spread.

As it was not based on any political program, fascism used rituals and ceremonies to appeal to emotions. Paxton demonstrates that fascists were preoccupied with community decline and victimhood. They sought unity, purity, and nationalist mobilization and wanted unquestioned devotion to the community and its leader. Many fascists played an active role during the First World War, and they adored violence and sought to materialize the final victory of their chosen race or nation over what they saw as its inferior opponents.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Explaining the anatomy of fascism, Paxton deconstructs the myth that fascist movements seized power by force. It was liberals and conservatives, frightened not by fascism but by the Left, who accepted fascists into their coalition governments and gave them the opportunity to govern. In Italy, despite the fact that the pan-Italian fascist march into Rome turned into a fiasco, the conservatives gave Mussolini the chance to enter into a coalition government. What the Italian fascists had proved was that they could successfully crush the Left, as they did in North Italy, for the sake of the local great landowners and with the help of the local state apparatus. Similarly, other European fascists tried to convince conservatives and businessmen that only they could handle the communists and protect the social and economic order. German fascists were successful in that task and came to power in the early 1930s with the help of German conservatives and businessmen. In Romania, where the Left was not an actual threat, conservatives not only did not need fascists, but they crushed their three coups.

German fascists created a structure parallel to the state apparatus, while the Italians relied mostly on the existing bureaucracy. The problem that both faced was their radical party members, who did not want the reestablishment of the old authoritarian regimes but a “permanent revolution” that would succeed in maintaining radicalization in the fascist regimes. However, Mussolini never succeeded in gaining absolute control over his party; he chose normalization rather than radicalization. Hitler, on the other hand, personally controlled his subordinates and promoted competition between them as to who would prove the most radical. Fascist radicalization reached its ultimate stage in Germany, and the Holocaust is an example of what that radicalization meant. Nazi policy on “inferiors” evolved from discrimination to expulsion and to extermination. Hitler’s subordinates in eastern occupied territories competed with each other in implementing the Final Solution and came up with even more extreme actions than the Nazi leadership required, which led to a chaotic situation during wartime. Ironically, although the war was promoted as a means to benefit the nation, it was a war that destroyed the fascist regimes.

Paxton offers a thorough guide to fascism. In addition to earlier fascism, he also discusses the presence of fascism inside and outside of post-war and post-1989 Europe and argues that in all democratic countries, some citizens flirt with the idea of denying established freedoms to fellow citizens and social groups. He also reviews the various, but mostly short-lived, fascist or proto-fascist movements and parties in the United States and what he considers the paradox of not having a fascist movement against the Civil Rights movements in the 1960s.

Paxton’s study is crucial now, in an era of major freedom setbacks, massive xenophobia, and openly neo-fascist movements and parties gaining momentum and entering European parliaments and governments. As Paxton says, “[f]ascists are close to power when conservatives begin to borrow their techniques, appeal to their ‘mobilizing passions,’ and try to co-opt the fascist following.” That’s important to remember.

Charalampos Minasidis is a European Research Council Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Centre for War Studies at University College Dublin, working on “The Age of Civil Wars in Europe, c. 1914–1949” ERC Advanced Grant Project. His research explores Greek historical actors’ involvement in different European civil wars, the international influences on their thinking and actions, and their life trajectories from the early 20th century until the Greek Civil War. Charalampos completed his PhD in History at The University of Texas at Austin in 2023.

______________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.