From the editors: In 2021, Not Even Past launched a new collaboration with LLILAS Benson. Journey into the Archive: History from the Benson Latin American Collection celebrates the Benson’s centennial and highlights the center’s world-class holdings.

On February 24, 1999, the Catholic Episcopal Conference of Argentina issued a stern rebuke of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, one of the country’s foremost human rights organizations. The bishops of the conference declared themselves “acutely surprised and deeply indignant” at the Mothers’ criticism of Pope John Paul II, who had recently called for the release of Chilean ex-dictator Augusto Pinochet from his arrest in the United Kingdom.[1] The bishops claimed to speak with one voice, emphasizing in no uncertain terms their support for John Paul II’ defense of the right-wing general who oversaw the torture and killing of thousands of Chileans in the 1970s and 1980s.

For Argentines who remember the darkest days of the country’s own military dictatorships, the last of which governed from 1976-1983 and killed up to 30,000 people in the so-called “Dirty War,” the Catholic bishops’ equivocation on human rights questions was no surprise. Emilio Mignone, an Argentine lawyer and human rights activist, scathingly described the Catholic establishment as a “web of mediocrity, cowardice, and complicity” in relating to the brutal 1976-1983 dictatorship.[2] Historian Martín Obregón observes that traditionalist and conservative bishops in Argentina exercised outsize influence among their colleagues, providing legitimacy for the dictatorship by attacking its critics and justifying its repression.[3] It is these conservative bishops and their enablers who tend to receive the most attention in accounts of the Argentine Church during the second half of the 20th century, and who have given the country’s Church a reputation as a barrier to reform and progressive politics.[4]

Yet two sets of documents in the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas belie the image of the Argentine Church as a homogeneous conservative force. Indeed, the Ecclesiastical Guides of the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires, dating to the early 1970s, and the Bulletins of the Episcopal Conference of Argentina suggest a more nuanced account in which features of the institutional Church constrained the reformist and progressive bishops who sought to defend human rights during the Dirty War. By examining the institutional Church, both locally and nationally, these documents help us understand the origins and limits of individual bishops’ power. The documents also show that this power may be understood through the same lens through which we analyze the power of political actors such as executives and legislators, that is by evaluating their institutional context.

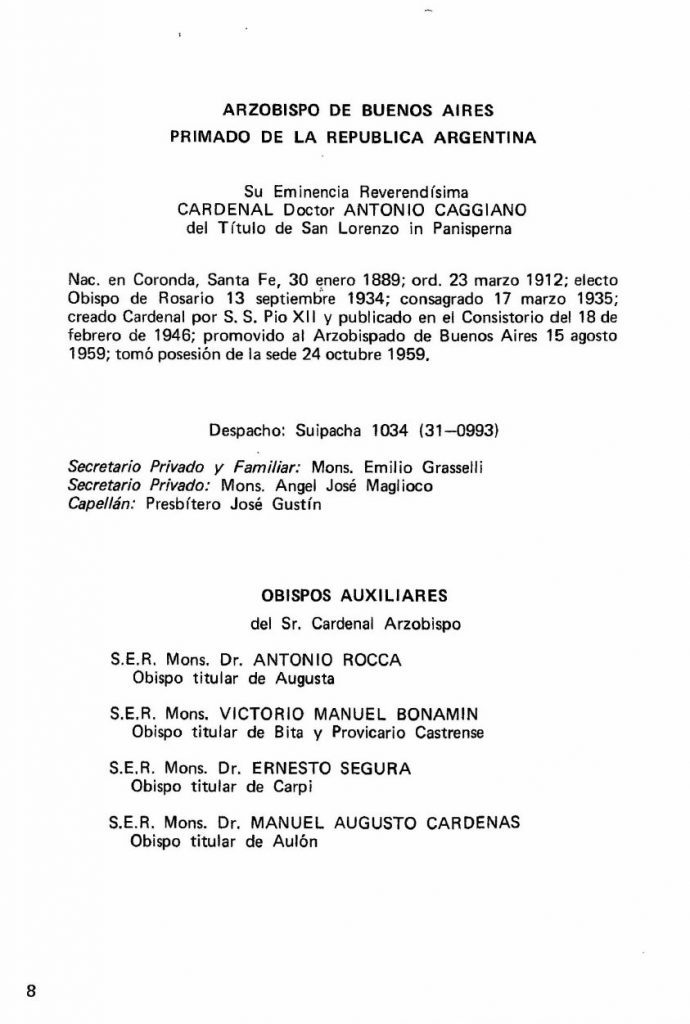

The structure of the Catholic Church gives bishops broad authority over the activities of the dioceses with which they are entrusted.[5] However, the 1971 Ecclesiastical Guide of the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires shows that, around the time of the Dirty War, Archbishop Antonio Caggiano (1959-1975) had to exercise this authority through a complicated web of councils, agencies, and religious subordinates. Reporting to the archbishop were four auxiliary bishops, seventeen members of the Curia—a kind of executive cabinet—an ecclesiastical tribunal, councils for liturgy, priests, community missions, and doctrine, seminaries, education commissions, and various dependent organizations such as publishing houses. Caggiano, through this bureaucracy, oversaw 155 local parishes, 124 female religious orders, 51 male religious orders, 14 institutes of higher education, 262 Catholic schools, religious presence in 40 medical facilities, and more than 100 charitable, cultural, and professional lay organizations including Catholic Action—a group, committed to serving the poor, that the dictatorship sought to contain. Fourteen years later, there were 14 new parishes, 14 additional members of the Curia, a half-dozen new commissions, ten more institutes of higher education, and three more religious orders in the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires.

Such statistics tell a larger story. A bishop in late-20th-century Argentina, despite his lofty title as a “vicar of Christ” and subordinate only to the pope himself, was, in essence, the chief administrator of a vast religious bureaucracy. His ability to defend human rights depended upon the cooperation of many subordinate officials, such as priests. Conversely, these subordinate officials could impede a bishop who supported or tolerated the military dictatorship during the Dirty War. Priests from religious orders, for example, had greater autonomy from the bishop and more opportunity to subvert him.[6] Using data on religious orders from the Ecclesiastical Guide, I show in my dissertation that progressive orders in Buenos Aires were associated with less repression around the parishes in their charge—despite Archbishop Juan Carlos Aramburu’s (1975-1990) passivity and permissiveness before the dictatorship.

The Passionists, or Pasionistas, were among the progressive religious orders in Buenos Aires. The 1971 Ecclesiastical Guide identifies Bernardo Hughes as the head priest of the Passionist parish of Santa Cruz. Even then, years before the Dirty War began—and under the nose of the prior 1966-1973 military dictatorship—Hughes began to shelter and assist human rights activists. The Nazareth retreat house, which opened in 1972, became a place of “reflection and encounter” for reformers including labor activists, politicians, and, by the time of the Dirty War, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Even when military agents in 1977 arrested some of the Mothers who met at Santa Cruz, Hughes’ successor Carlos O’Leary continued to shelter activists in defiance of the dictatorship.[7] The Ecclesiastical Guide suggests O’Leary persevered in his defiance: he remained priest at Santa Cruz as late as 1985.

Even if a bishop who opposed the Dirty War could muster priests who defended human rights, the Bulletins of the Episcopal Conference of Argentina reveal how opposition to the military regime died on the vine at the national level. In these conferences, bishops meet for two or three days in plenary sessions to consider a series of resolutions—on topics related to Church governance, current domestic social, political and economic issues, pastoral concerns, religious events, and relations with the global Church—referred to them from a smaller Permanent Commission. The plenary session then votes on resolutions. The Episcopal Conference also selects executive officers: a president, two vice presidents, and a secretary general. Thus, the Permanent Commission and executive officers serve as gatekeepers for the advancement of resolutions among the bishops.

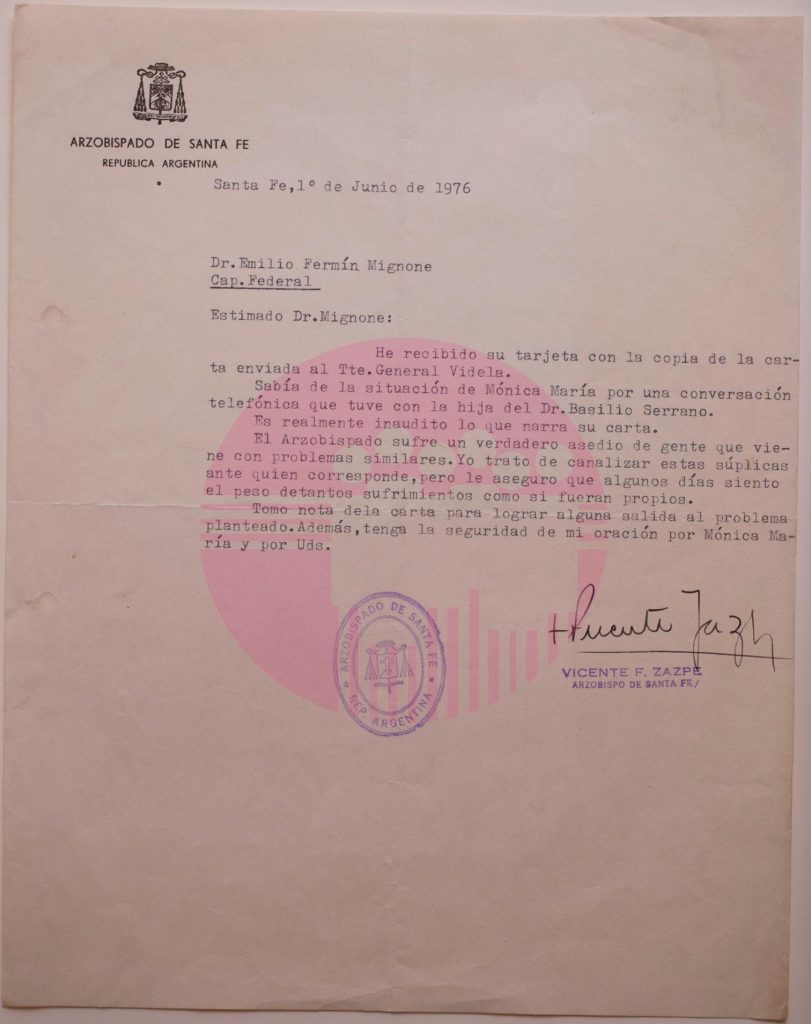

At the beginning of the Dirty War, when the bishops’ support for human rights would have been most critical, the Episcopal Conference gatekeepers were conservatives. The president was the arch-traditionalist Adolfo Tortolo, a personal friend to military dictator Jorge Rafael Videla who gave tacit blessing to the military on the day it seized power in a coup. Furthermore, of the sixteen members of the Permanent Commission in 1976, I was only able to identify five with any record of supporting human rights before or during the Dirty War. Episcopal Conference resolutions in 1976 reflected this composition, with a May “pastoral letter” pointing to the importance of domestic security alongside personal freedom while failing to attribute ongoing human rights violations to the military. The pastoral letter passed the plenary sessions despite the objections of at least eight bishops.[8] By 1977, with Tortolo replaced by the more moderate Raúl Primatesta and with human rights supporter Vicente Zazpe as a vice president, the bishops’ statements toward the military hardened, though inconsistently so.[9]

Even though the bishops’ statements became more critical of the military over time, supporters of human rights remained outnumbered in plenary sessions. Of the 57 diocesan bishops seated in 1976, I could identify only 22 who worked against the Dirty War. Among the rest, 26 were traditionalists or conservatives ideologically aligned with the dictatorship and nine were ambivalent or equivocal (information on the final bishop was scant).[10] The median diocesan bishop—whose views on the Dirty War we would expect majority-approved Episcopal Conference resolutions to reflect—therefore arose from this latter category. Small wonder, then, that the bishops’ statements released during the Dirty War took such an equivocal stance on questions of human rights, repression, and, later, transitional justice.

Between them, the Ecclesiastical Guides and Episcopal Conference Bulletins from the Benson Collection reveal the internal politics and organization of the late-twentieth century Argentine Catholic Church. Individually, bishops administered sprawling and potentially uncooperative bureaucracies. Collectively, the national agenda for the Argentine bishops rested in the hands of conservative leadership, while the votes needed for a majority in the Episcopal Conference lay with bishops such as Juan Carlos Aramburu. Far from a homogeneous front “indignant” about the demands of human rights organizations, these sources, stored in the Benson collection, show progressives at every level of the Argentine Church who nevertheless lacked institutional power and numerical strength sufficient to break into view at the national level. In this way, they reveal a more complex story of Argentinian history.

Pearce Edwards is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Emory University. His research agenda focuses on repression and resistance in authoritarian regimes. In particular, he studies how non-state actors affect regime repression, showing how social elites and ordinary citizens may constrain or enable the efforts of security institutions to eliminate popular threats to authoritarian rule. Related areas of interest include how repression affects politics and public attitudes in the short and long term. His research has been published in the British Journal of Political Science, the Journal of Conflict Resolution, and the Journal of Peace Research. He can be found on Twitter @pearceaedwards.

[1] https://elpais.com/diario/1999/02/24/internacional/919810816_850215.html

[2] Mignone, Emilio F. 1986. Witness to the Truth: The Complicity of Church and Dictatorship in Argentina, 1976-1983. New York: Orbis Books, 28.

[3] Obregon, Martin. 2005. “La iglesia argentina durante el “Proceso” (1976-1983).” Prismas, Revista de historia intelectual 9:259-270.

[4] Gill, Anthony. 1998. Rendering Unto Caesar: The Catholic Church and the State in Latin America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[5] http://www.vatican.va/archive/cod-iuris-canonici/eng/documents/cic_lib2-cann368-430_en.html

[6] McDermott, Rose. 2004. “Ecclesiastical Authority and Religious Autonomy: Canon 679 Under Glass.” Studia Canonica 38(2):461.

[7] Taurozzi, Susana. 2017. “Iglesia de la Santa Cruz, 8 de diciembre de 1977. Itinerarios de vida y memoria.” XVI Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata, 5.

[8] Mignone 1986, 21.

[9] U.S. State Department. 2017. “Doc No. C06342764” Argentina Declassification Project, 9.

[10] Numbers are based on original data collected by the author.