In 2014, we enter the centennial of one of history’s most terrible conflicts. Originally (and quite appropriately) named The Great War, the four-year conflict claimed roughly eight and a half to nine and a half million lives on the battlefield, not to mention millions of civilian war deaths as well as many millions more who died in related events such as the Russian Revolution and Civil War and the Flu epidemic of 1919.

Not surprisingly, none of the veterans who fought and bled in the struggle has lived long enough to see the centennial. Even if someone found a way to get around army regulations and sign up at sixteen, he or she would have to be 112 today. Consequently, since the year 2000, almost all of the nations that participated in World War I have seen their last World War 1 veterans die off.

Since 2000, there have been an increasing number of news stories about such men as Claude Choules (British sailor), Harry Patch (British soldier), and Frank Buckles (American soldier), all of them male, two of them combat veterans. But as the countdown, and by extension, the die-off continued, the news media finally came to focus more closely on another, somewhat more unlikely candidate for the title “last living veteran of World War I.” In May 2011, with the death of Coules, that title went to his fellow Brit who had not yet received anywhere near as much attention—Florence Green of the Royal Air Force.

Although not the oldest in years at the time of her death on February 4, 2012 (she was “only” 110 while two of her fellow veterans had lived to be 111), Florence Green came closest to making the centennial of any surviving veteran of World War I. Born Florence Patterson in February 1901, she joined the women’s branch of the newly formed Royal Air Force (formerly, the Royal Flying Corps) in September, 1918, two months before the armistice. At the time of her enlistment, she was only seventeen. During her brief time in the military, Patterson worked in the officer’s mess at two air force bases, Marham and Narborough, not far from the England’s east coast. While she was not a combat veteran (few women were), she had, as the British put it, “done her bit” and done it underage and without the prompting of a draft. Her service is one more example of the role women played in WW1 as nurses, shell makers (the so-called girls “canaries” or “girls with yellow faces”), and the thousands who not only kept the home fires burning, but who poured into industry and agriculture, making possible the war effort. Asked what it felt like to be 110, Florence Green is reputed to have replied, “not much different to being 109!” Whether or not the female of the species is deadlier than the male, in this case at least she proved to be the most long-lived—the last person standing.

As the countdown to the centennial of World War I continued, a number of surviving veterans came into the spotlight. These are a few of their stories.

Claude Stanley Choules, last combat veteran (died May 5, 2011; age 110)

Born in England in 1901, Claude Choules, came from a broken home. Several older siblings, who had been taken out to Australia, joined the Anzacs and participated in the landings at Gallipoli in 1915. Choules himself started his naval career at the age of 15 when he signed onto a British training ship, having been turned down a year earlier when he tried to enter the army as a bugler. In October 1917, his training completed, he transferred to a British battleship, stationed at the main naval base at Scapa Flow. Although he was too late to catch the one great sea battle of World War I, fought at Jutland in spring, 1916, late in the war his ship did tangle with a zeppelin, making him a bona fide combat veteran. Choules witnessed the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet in November 1918, and the scuttling of that fleet by the German sailors the following June. He continued to serve in the British navy until 1926, when he transferred to the Royal Australian Navy in which he served throughout World War II, finally retiring only in 1955. Having moved to Australia, he would remain there for the rest of his life.

Henry John Patch (better known as Harry), last to have fought in the trenches on the Western Front (died July 25, 2009; age 111)

Born in 1898, Harry Patch became known in his final years as “the Last Fighting Tommy” — a nickname given British soldiers as long ago as the nineteenth century, short for Tommy Atkins. He was the last man known to have experienced the horrific trench warfare of the Western Front. In October 1916, at the age of 18, Patch was drafted into the army, too late for the battle of the Somme in which the British suffered 60,000 casualties in a single day, but in time for what many regard as the most horrible battle of the war, Passchendaele or 3rd Ypres, where men and animals actually sank into the mud of Flanders. He was part of the crew operating a Lewis Gun, a rapid fire weapon used in World War I, when on September 22, 1917, he suffered a massive injury from an exploding shell, which instantly killed three of his “mates.” It would be Patch’s last battle; he was still recuperating in Britain fourteen months later when the armistice was signed.

Patch, who outlived his three wives and two sons, was not only the last surviving veteran to have fought in the trenches, he seems also to have been the most profoundly quotable—at least toward the end, when he was finally willing to speak of his war experiences.

Remembering that moment of terror experienced by so many men on both sides: “If any man tells you he went over the top and he wasn’t scared, he’s a damn liar.”

Characterizing war in general: The “calculated and condoned slaughter of human beings” [that] isn’t worth one life.”

When meeting the last survivor who had fought on the other side at Passchendaele:

Earlier this year [2004], I went back to Ypres to shake the hand of Charles Kuentz, Germany’s only surviving veteran from the war. It was emotional….We’ve had 87 years to think what war is. To me, it’s a license to go out and murder. Why should the British government call me up and take me out to a battlefield to shoot a man I never knew, whose language I couldn’t speak? All those lives lost for a war finished over a table. Now what is the sense in that?

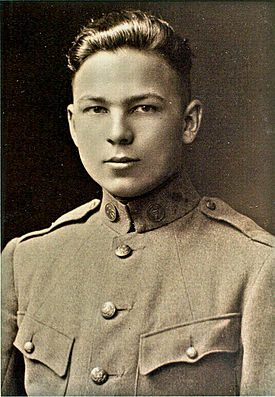

Frank Buckles, last American who served in World War I (died February 27, 2011; age 110)

Born in February 1901, the same month as Florence Green, Frank Buckles tried to join up in 1917, the year America entered the war, despite being only sixteen. After being turned down by both the marines and the navy, he managed to convince an army recruiter to take him in. He was told that the fastest way to get to the front was to drive an ambulance, which he did and, as a result, he is not technically classified as a combat veteran. Rising to the rank of corporal, he served as a driver in both England and France. After hostilities ended, Buckles took part in civilian relief operations and escorted captive soldiers back to Germany. Discharged in 1919, he returned to the Unites States where he actually met his former commander, General Pershing, during a dedication ceremony in Missouri.

Following the war, Buckles became a chief purser on passenger liners and cargo ships. In the 1930s, when his ship stopped at German ports, he had a chance to watch the rise of Nazism. In 1940, business brought him to the Philippines and in January 1942, during the Japanese invasion, he was captured. Buckles spent the next three years interred in civilian prison camp from which was liberated only in 1945. He would spend the rest of his life, over six decades, living in West Virginia where he and his wife owned a farm. In February 2008, he became America’s last surviving veteran of the war. Even then, he remained active in the quest to establish a National World War I memorial on the National Mall in Washington DC.

Charles Kuentz, a veteran who fought for both Germany and France (died April 7, 2005, age 108)

At the time of his death, Charles Kuentz was believed to be the oldest surviving veteran of the German army who had fought in World War I. Clearly, that is what Harry Patch thought when the two met and shared their reminiscences at Ypres the year before. Although this was later found to be untrue—in fact, the oldest German soldier was Erich Kastner who died three years after Kuentz at age 107—the case of Charles Kuentz merits attention for another reason.

During the First World War, he fought on the German side and during the Second, he fought (albeit briefly) for the French!

This remarkable about-face in national allegiances resulted from the latest chapter in one of Western Europe’s longest running feuds—the conflict over Alsace-Lorraine. Lying between France and Germany, this territory was considered German until well into the early modern period. However, in the 17th century, the “Sun King,” Louis XIV, seized Alsace for France, while some decades later his successor, Louis XV, added Lorraine. During the next century and a half, the provinces despite the fact that many Alsatians continued to speak of a German dialect, became increasingly French in their outlook. Then came the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71. After the German victory, all of Alsace and a significant part of Lorraine were regained as the spoils of war by the new German Empire. In the succeeding decades, the Alsace-Lorraine question remained a bitter bone of contention in Franco-German relations leading up to the First World War.

Having been born in Alsace when it was German territory, Kuentz was drafted into the German army at the age of 19. Over the course of several years, he fought for Germany on both the Eastern and Western fronts. In November 1918, immediately following the armistice, he joined many other members of the fast disintegrating army when he simply walked away and returned home to Alsace. The following year, the Versailles Peace Treaty that officially ended the war with Germany, transferred the “lost province” back to France. Since Kuentz now opted to embrace French citizenship, he was once again called to the colors in 1939, this time by the French, though on this occasion his military service was short-lived. With the surrender of the Third French Republic following the disastrous campaign of 1940, Alsace once again became German and Kuentz again found himself a German citizen. His son, with the very French name of Francois, joined the German SS and died fighting in Normandy in 1944.

Following the second war, Kuentz once again became a Frenchman and remained one until the end. At his death in 2005, his coffin was draped with the French flag.

Don’t miss more recent NEP articles about World War I:

Read about the mysterious censorship of Wilfred Owen’s personal correspondence

And explore Harry Ransom Center’s incredible collection of WWI propaganda posters