By Amina Marzouk Chouchene, PhD candidate, Manouba University

There has been a consistent recent interest in tracing the fragile nature of the British Empire. An increasing number of historians such as Richard Price, Kim Wagner, Harald Fisher-Tiné, and Jon Wilson have considered the precariousness of empire from different perspectives.[1] The ever-present threats of what was often called “going native,” the debilitating effects of heat, colonial rebellions and insurgencies, and the supposedly treacherous behavior of indigenous peoples were some of the concerns that triggered a sense of colonial vulnerability. Instead of focusing on the strength or successes of the British Empire, there is a now a new emphasis on its fragility. Marc Condos’s The Insecurity State confirms the findings of this impressive wave of research on the vulnerability of empire.

Condos’s book takes special interest in highlighting the precariousness of British rule in Punjab, which was widely viewed as a loyal and stable province. From the outset, Condos persuasively argues that “British colonial rule in India was a fundamentally anxious and insecure endeavor.” Most interesting, Condos suggests that “brute displays of power” like the Amritsar Massacre of 1919, “were actually manifestations of colonial weaknesses and vulnerability rather than strength” (3). This is a key argument in The Insecurity State. Yet the book does not seek only to understand the “logic” of colonial violence. It also examines the tense relationship between the empire’s commitment to the rule of law and the need to maintain its stability on the ground and how the institutions and mechanisms that were assumed to buttress colonial power became persistent sources of insecurity (18).

Condos deals with these questions in five thematic chapters. Chapter one is an overview of British rule in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries during which British colonial power in India was constantly challenged. The British fought, for instance, wars against Mughal successor states mainly the Marathas and the kingdom of Mysore.

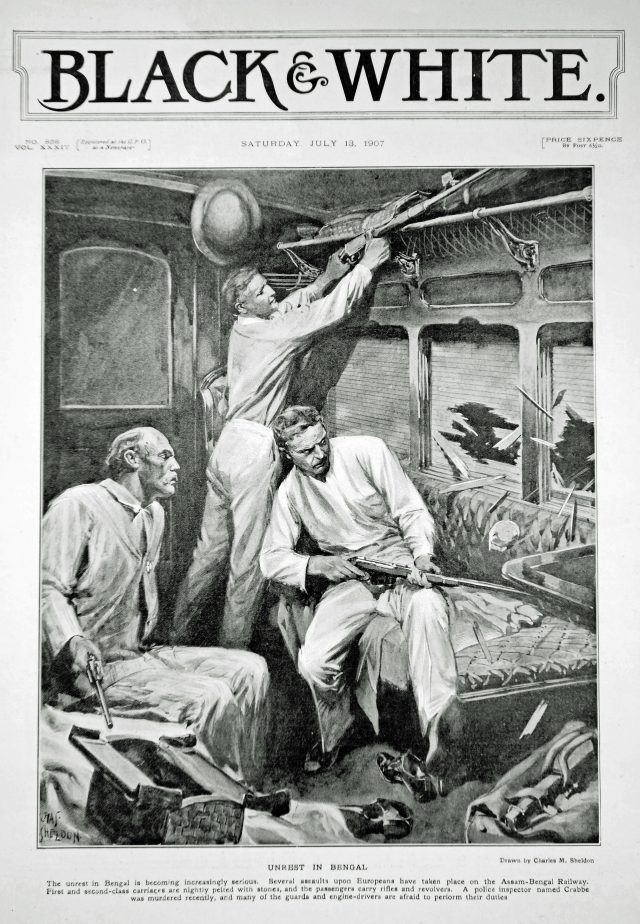

Chapter Two, deals with the Punjab government’s determined attempts to tame the “warlike” nature of Sikh soldiers after the demise of their empire through a series of schemes, which aimed to turn them into peaceful farmers. Following the Rebellion of 1857, the Sikhs were perceived to be loyal and were recruited by the Indian Army. Nevertheless, Condos clearly demonstrates, through a wide variety of primary sources including private papers, letters, personal memoirs, newspapers and periodicals, and contemporary monographs, that Punjab authorities were consistently anxious about the persistent threats of a Sikh rebellion. The rural unrest in response to the Colonization Bill commonly known as the Punjab disturbances of 1907 affirmed these fears. They “served as an indelible reminder to colonial officials of the perennially precarious situation which existed in India when even the most ‘loyal’ sections of Indian society could turn against them” (21).

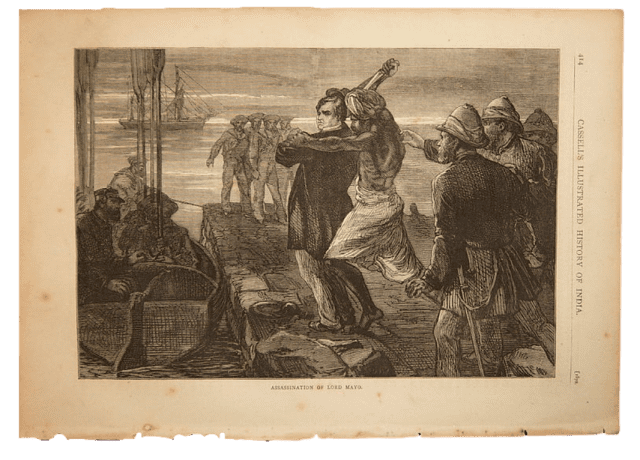

Chapter Three considers the suppression of the “Kooka outbreak” and the extensive violence that accompanied it. The execution of 49 Sikh rebels and sixteen prisoners “by blowing them from the mouths of artillery guns” aroused considerable controversy. It brought to the fore the fraught relationship between the British ideal of the rule of law and the realities of empire where colonial officers’ transgressed laws in order to ensure the stability of the colonial regime (17).

The radicalization of colonial rule is much more evident in chapter four which explores the Murderous Outrages Act of 1867.This gave colonial officials enormous power to instantly execute those identified as so-called fanatics in Punjab. The final chapter discusses how the employment of Punjabi soldiers and policemen in Britain’s overseas empire provoked deep anxieties among British India’s officials. There were intense fears that the “popularity of overseas service” was weakening Indian Army amid widespread rumors that Punjabis were joining military service with imperial rivals such as the Germans and the Ottomans.

Taken together the chapters counteract one of the enduring myths that British rule in India was “a powerful, confident, and nearly indomitable force” (10). Most importantly, Condos’s book offers a fresh perspective on the apparently contradictory relationship between a wider colonial sense of vulnerability and the persistent use of violence. While usually perceived as an obvious sign of imperial power and invincibility, colonial violence surfaces in The Insecurity State as the outcome of constant anxieties and insecurities. Although the book lacks a theoretical framework for defining the central concept of anxiety, which can be found for example in the work of Alan Hunt and Joanna Bourke, it is nonetheless highly valuable in providing us with a better understanding of the lived experience of empire.[2] It could also open up new avenues for future research on colonial violence and vulnerability in other imperial settings.

[1] See Richard Price, ‘The Psychology of Colonial Violence,’ in Dwyer P., Amanda Nettelbeck, eds. Violence, Colonialism, and Empire in the Modern World (Cham, Switzerland,2018)Kim Wagner, Amritsar 1919: an Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre (London,2019), Harald Fisher Tiné, Anxieties, Fear, and Panic in Colonial Settings: Empires on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Houndmills,2016), Jon Wilson, India Conquered: Britain’s Raj and the Chaos of Empire (London, 2016)

[2] See Alan Hunt, ‘Anxiety and Social Explanation: Some Anxieties about Anxiety,’ Journal of Social History, vol.32,no.3,1999,pp.509-528, Joanna Bourke, Fear: a Cultural History (London,2005)