by Diego A. Godoy

From the editors: In 2021, Not Even Past launched a new collaboration with LLILAS Benson. Journey into the Archive: History from the Benson Latin American Collection celebrates the Benson’s centennial and highlights the center’s world-class holdings. This article first appeared in Tex Libris, a blog from the Office of the Director of the University of Texas Libraries. The original can be accessed here.

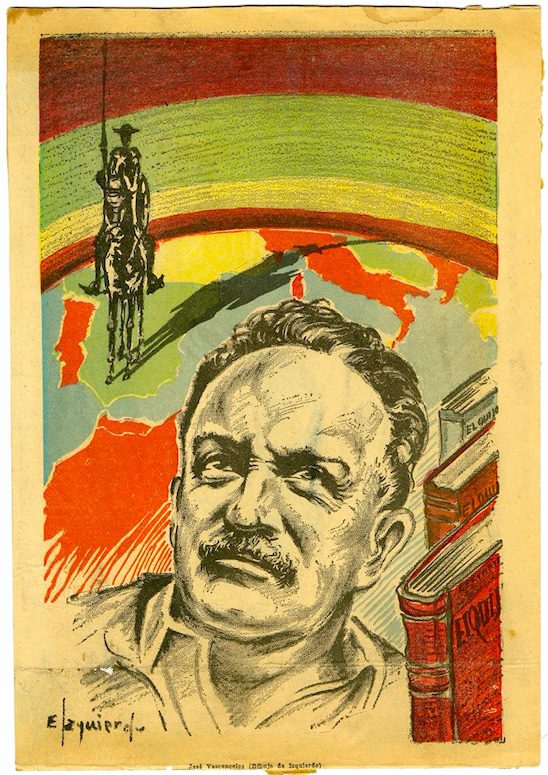

The Benson Latin American Collection is home of the archive of Mexican politician, writer, and philosopher José Vasconcelos (1881–1959). In this short essay, Diego Godoy describes a man of contradictions, “the personification of both the brightness and darkness” of post-revolutionary Mexico.

One has to admire José Vasconcelos: the young law student who became a leading ateneísta —a member of the intellectual cohort that undid positivism’s decades-long stranglehold on Mexican political, social, and cultural life; the lawyer who was appointed rector of UNAM while still in his thirties; Mexico’s first Secretary of Public Education, who deployed teachers and mobile libraries to poor, rural schools and published affordable editions of literary classics; the mastermind behind Mexican muralism—picture him sitting with José Clemente Orozco, splitting a bottle of tempranillo (Vasconcelos hated distilled spirits), explaining how Orozco and other artists will bring history to the hoi polloi by frescoing colonial edifices; the Culture Czar of the Mexican Revolution.

But one can also loathe him. As the leading theoretician of official mestizophilia, he exalted the Iberian half of the mestizo equation above the Indigenous; if this is not wholly clear in the first part of La raza cósmica, read the accompanying travelogue of South America. Perhaps more egregious was his flirtation with fascism, which reached its highest (or lowest) point when he took the reins of a Third Reich–funded cultural magazine. His love life was similarly troubling: his refusal to fully commit to his mistress, the writer Antonieta Rivas Mercado, inspired her to put a bullet through her heart inside Notre-Dame—with Vasconcelos’s own pistol, no less. And then there was this slight, published in El Universal: “Barbarism commences where the consumption of guisos [stews] gives way to that of carne asada [grilled beef];” a jab, presumably, at the stereotypical brusqueness of my own father’s people—northern Mexicans.

Consider Vasconcelos the personification of both the brightness and darkness of the revolutionary project. In this sense, he was not much different from the other protagonists of the first half of Mexico’s twentieth century. Yet his intellectual and cultural impact dwarfed and far outlived that of his contemporaries.

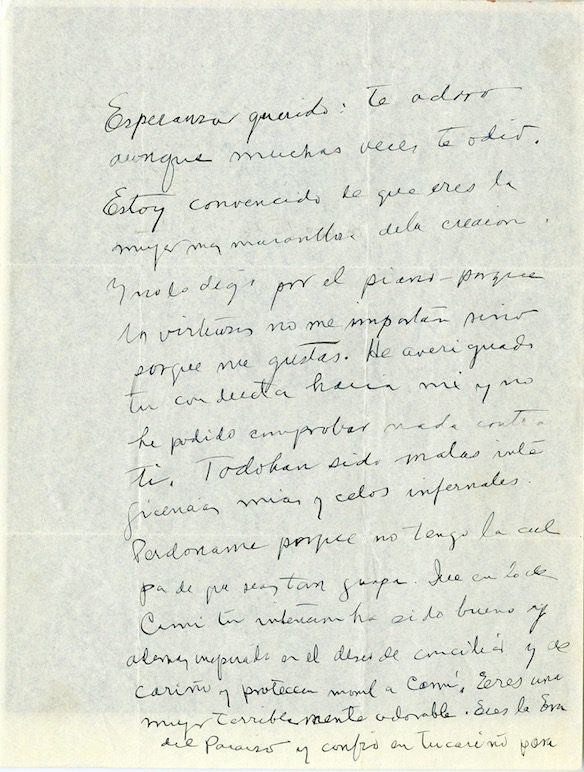

Naturally, there is a good deal published about this maestro de la juventud de América, with the most comprehensive treatments having appeared pre–Moon Landing. More books, chapters, and essays have cropped up since then, many of which grapple with the themes of his work in oblique ways. A new English-language book (it is a largely hispanophone field), perhaps one offering unique focal points and fresh interpretations, would certainly be welcome. And while traditional cradle-to-grave biographies have become academically passé, what is often cold-shouldered by academia tends to be a reliable barometer of mass appeal. Should a researcher engage in such a project, he or she will be glad to know that the José Vasconcelos Papers at the Benson Latin American Collection contain correspondence (and divorce records) between Vasconcelos and his second wife, the pianist Esperanza Cruz. I suspect that many working historians might be dismissive of the man’s personal life. This would be unwise, because clever dashes of detail and anecdote can furnish scholarly writing and lectures with some badly needed flair. Either way, for the Vasconcelos-curious, this collection is the repository of choice.

The Vasconcelos Papers: A Closer Look

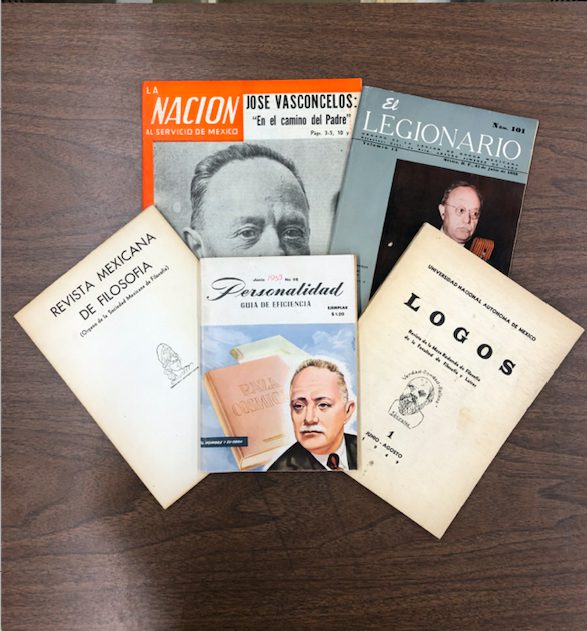

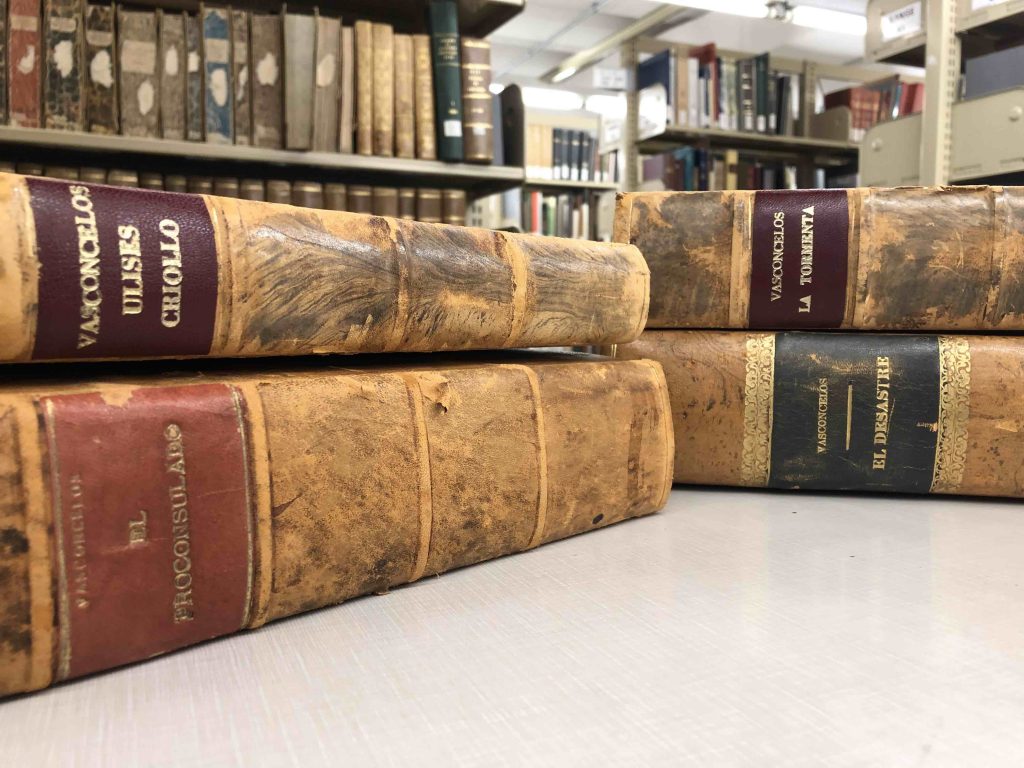

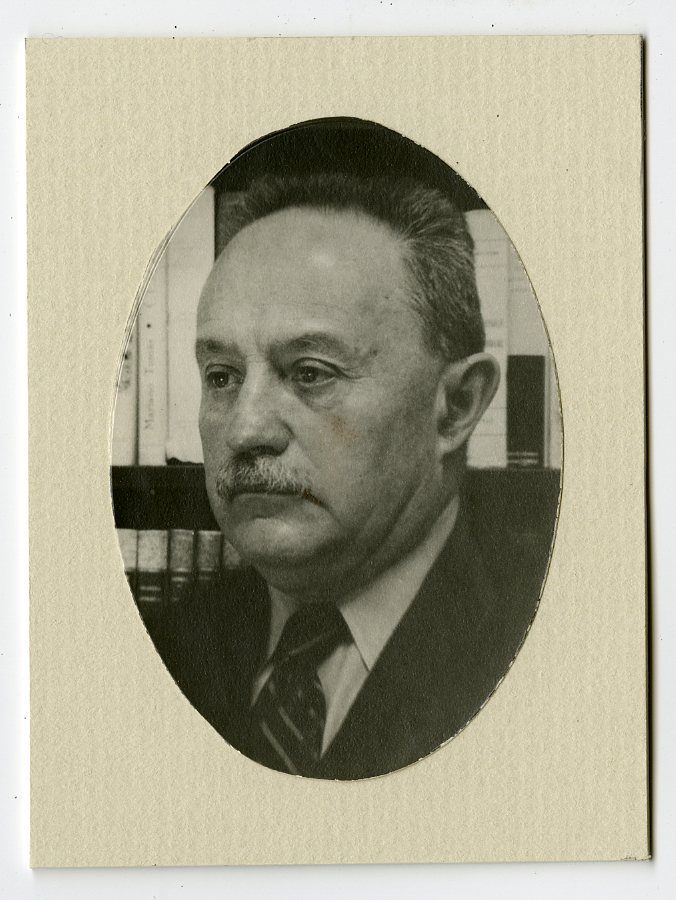

The José Vasconcelos Papers are divided into five sections. Correspondence contains the aforementioned letters to and from Esperanza Cruz, other relatives, and an array of writers. Among the latter group is Rodolfo Usigli, one of Mexico’s (and, indeed, Latin America’s) foremost dramatists, and Carlos Denegri, the legendarily unscrupulous, hard-drinking, sexist, insert-whatever-“ist”-you-want newsman—a veritable institution at Excélsior for some three decades. Biographical Materials holds photographs, artistic renderings of Vasconcelos, ephemera—conference programs, event invitations, coverage of his death—and a handful of personal items. Writings contains manuscripts and articles on a variety of subjects by Vasconcelos, as well as works by others reflecting on his cultural footprint. Of note is his four-part autobiography and another original, philosophical tract, La estética. Printed Materials includes journal, magazine, and newspaper articles by and about Vasconcelos, as well as books authored by him and those collected by or gifted to him. Lastly, there are two boxes of Oversized Materials: certificates, diplomas, event posters, newspaper clippings, and so forth.

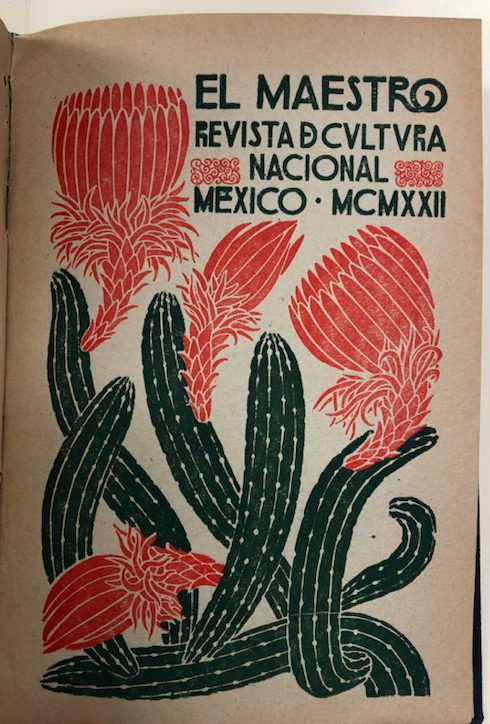

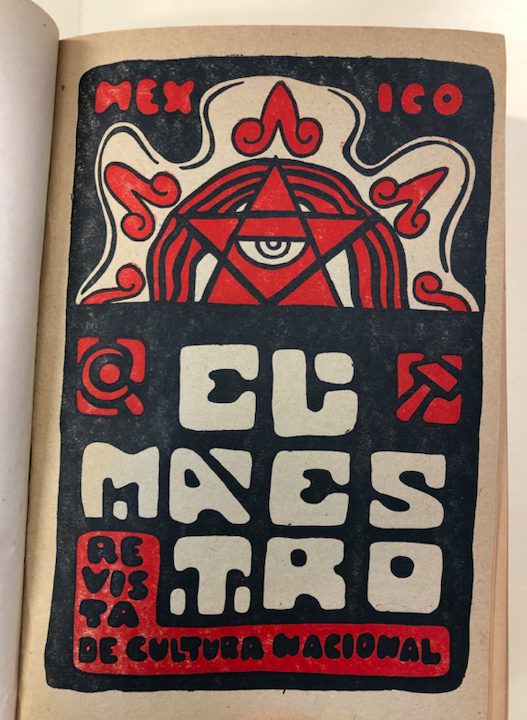

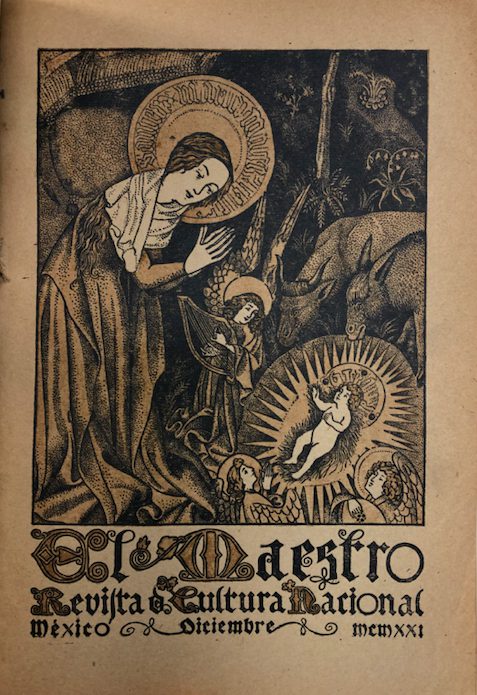

For those who remain uninterested in contributing more pages to the micro library of Vasconcelos Studies, or expelling more breath on the “Great Men” of history, the collection is replete with gems nonetheless. Let’s say that you are interested in the history of education in Mexico, or, perhaps more specifically, the post-revolutionary state’s efforts to cultivate the minds of its citizenry. In that case, digging through issues of the short-lived El Maestro: Revista de cultura nacional will be worth your time. Founded by Vasconcelos as a sort of general culture primer, the magazine aimed to diffuse literary, historical, philosophical, and pedagogical content to educators, children, and lifelong learners. In its pages, Ramón López Velarde garnered his reputation as Mexico’s national poet before his untimely death at 33, and educators found Spanish-language versions of Tolstoy and lessons detailing the “Practical Applications of Geometry.”

A particularly rich vein of material exists for those concerned with “bibliotechology” (as I suspect many reading this are). Vasconcelos’s conviction that “only books will lift this country out of barbarism” spurred the momentous creation of libraries—and the training of competent professionals to steward them—during his tenure as Secretary of Public Education. Under the auspices of his newly formed Department of Libraries and Archives, a young poblana named María Teresa Chávez Campomanes arrived stateside for graduate studies in library science at Pratt and Columbia. Following stints at the New York Public Library and the Library of Congress, she returned to Mexico. Her sterling intellect (and no doubt her connections) pried open the doors to coveted positions, including the directorships of the Biblioteca Benjamín Franklin and the Biblioteca de México. Yet her greatest legacy rests on having mentored a generation of librarians. As a professor at the Escuela Nacional de Bibliotecarios y Archiveros, a founder of UNAM’s Colegio de Bibliotecología, and the author of definitive guides to cataloguing and classification, she was instrumental in the professionalization of Mexican librarianship. Anyone investigating the history of libraries and cultural heritage institutions, higher education, or the Mexican state’s cultural apparatus will find the six years’ worth of correspondence between Vasconcelos and Chávez Campomanes indispensable.

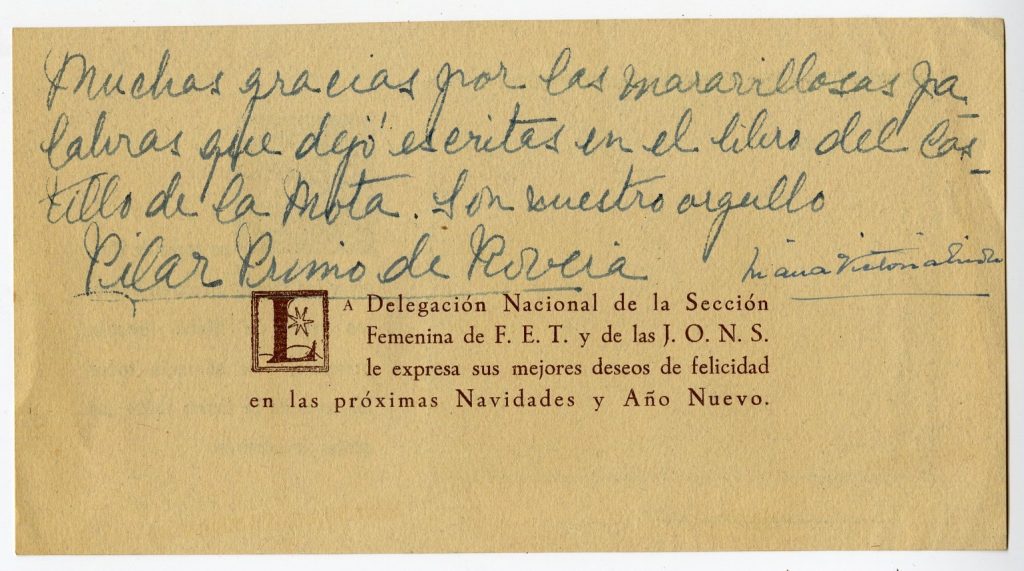

If you are like me, it is another woman’s name in Vasconcelos’s mailbag that will jump out at you: Pilar Primo de Rivera—the head of the Spanish Falange’s Sección Femenina, an organization whose raison d’être was to reinforce the belief that Spanish women should be seen (preferably in their husbands’ kitchens and bedrooms) and not heard. She was also, very briefly, the would-be Mrs. Adolf Hitler, but the Spaniards’ harebrained scheme to forge a Hispano-Teutonic dynasty was scrapped upon discovery of the Führer’s unitesticularity. Some might consider her a surprising correspondent for a man as erudite and seemingly enlightened as Vasconcelos. But the problem with the erudite and seemingly enlightened is that they, too, can be seduced by truly awful ideas. Indeed, the intelligentsia may be even more susceptible because they can readily perform the mental gymnastics necessary to rationalize intellectually or morally bankrupt positions—look no further than the Twittersphere to see otherwise brilliant people with Ivy League credentials hurl critical thinking out the window.

A right-wing analogue can be found in 1930s Latin America, when many of the region’s prominent literati, not the least of whom was don José, were among the torchbearers of an emergent “clerical and hispanophile right-wing nationalism,” as Pablo Yankelevich put it. But exactly how does one go from cultural revolutionary to reactionary? What explains a broadly liberal humanist’s descent into a regressive Catholic conservatism? And not your grandfather’s variety of conservatism either, unless he happens to be a porteño with a curiously German accent. Perhaps Vasconcelos’s faith in democratic principles dissipated after the events of 1929, when his presidential hopes were dashed. Coupled with a battered ego and festering resentment, this is a compelling explanation. So is the company he kept during his post-election exile, notably Leopoldo Lugones, the Argentine poet and accomplice in José Félix Uriburu’s corporatist military regime. No doubt Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles’s ferocious anticlericalism, and comparable atrocities perpetrated by Spanish anarchists and communists, also accelerated Vasconcelos’s rightward shift.

Some of the flesh for these bones may be found in Vasconcelos’s correspondence with the Spanish writer José Manuel Castañón. Hailing from Asturias, Castañón ran away from home at 16, but not for the usual reasons that teenagers flee. He aspired to join the ranks of Franco’s soldiers, and did just that in 1936. Five years later, he volunteered for the so-called Blue Division in order to fight alongside the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front. Castañón would eventually grow disillusioned with Francoism and publish accounts of his political 180 from his exile in Caracas.

Vasconcelos’s communication with compatriota Manuel Gómez Morín, however, might just yield more grist. An admirer of Miguel Primo de Rivera and the French protofascist thinker Charles Maurras, Gómez Morín wore many hats: law professor; university rector; banking czar; corporate lawyer; and most importantly, opposition party founder. His disenchantment with the post-revolutionary state began in the 1920s with President Álvaro Obregón handpicking Plutarco Elías Calles as his successor, Calles’s subsequent anti-Catholicism, followed by Vasconcelos’s failed presidential campaign, for which he served as unofficial treasurer. The 1930s proved no better for him and the politically like-minded, as President Lázaro Cárdenas’s progressive reforms clashed with major national and transnational companies, some of which counted on Gómez Morín for legal counsel. Fed up with the state of affairs, Gómez Morín founded the National Action Party (Partido Acción Nacional, PAN) in 1939. Many of its earliest followers and official candidates ran the gamut of right-leaning ideology, from Jesuit activists to sinarquistas, members of a Guanajuato-based, Nazi-founded political organization whose rallying cry was “Faith, Blood, Victory.” These days, the PAN is more synonymous with drug-warrior presidents, conservative middle-class voters (the party’s lifeblood), and fake-news-peddling, rosary-clutching middle-aged women. But its early quasi-fascist ties cannot be forgotten.

Spending a few minutes eyeing the finding aid—and Googling unfamiliar names, texts, and organizations—will reveal the remarkable research and teaching potential of this collection. Whether one is concerned with some understudied facet of Vasconcelos’s life or career, or seeks to investigate such disparate topics as Mexican librarianship or transatlantic fascism, the José Vasconcelos Papers will provide unique and unmatched sources.

Diego A. Godoy is a PhD candidate in Latin American history at The University of Texas at Austin. Before coming to Texas, he earned an MA in history from Claremont Graduate University. He is broadly interested in the intellectual and cultural history of the region. His particular focus is on the history of criminology, detection, and crime writing. He is author, most recently, “Inside the Agrasánchez Collection of Mexican Cinema” (2020) and “Confessions of an Archives Convert: Reflecting on the Genaro García Collection” (2021), both published in LLILAS Benson’s Portal magazine.

With thanks to Latin American Archivist Dylan Joy, who selected the archival images for this article.

Support the Benson Centennial! Visit benson100.org to learn more.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.