Why are some medieval kings still widely remembered today, when so many others have been forgotten? The monuments they commissioned sometimes keep their memories alive, but the kings of the distant past who loom largest in popular memory typically either ushered in a new age – like Charlemagne, the king of the Franks, crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the pope in 800 AD – or else they represent the end of an era – like King Arthur, a British leader who may have fought the Saxon invaders around 500 AD.

Like Charlemagne and King Arthur, the twelfth-century Indian ruler Prithviraj Chauhan stood on the cusp of two periods in a time of great change. He has often been described as “the last Hindu emperor” because Muslim dynasties of Central Asian or Afghan origin became dominant after Prithviraj Chauhan’s death.

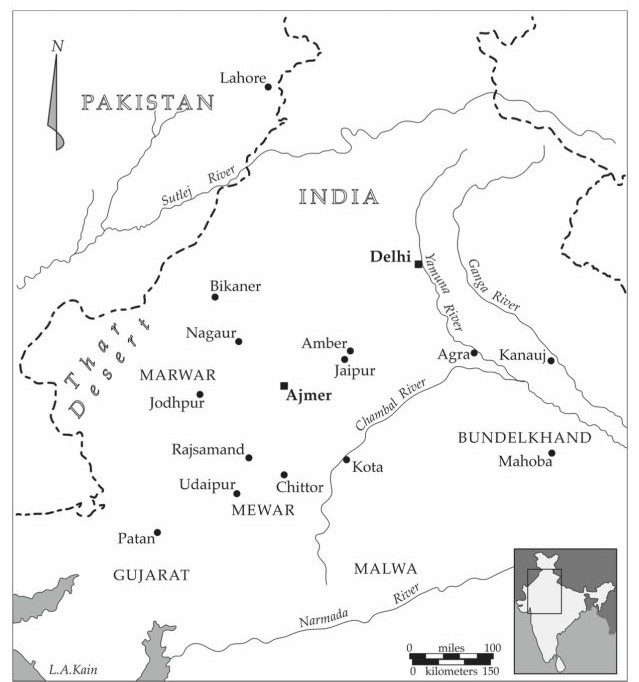

Prithviraj Chauhan is mentioned in history textbooks today mainly because he lost a major battle in 1192 against Shihab al-Din Muhammad Ghuri, based in Afghanistan. This defeat soon led to Muslim rule in much of North India under the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526) and the Mughal empire (1526- ca. 1750). Prithviraj Chauhan’s defeat had serious consequences: an influx of Central Asian and Afghan warriors, the adoption of Persian language and culture, and the spread of Islam. But his defeat in one battle does not seem important enough to justify the dozens of narratives about him that have been composed since his death. He continues to be remembered in India to this day. A three-rupee postage stamp bearing his name was issued in 2000 and a lavishly produced TV series on his life, “Prithviraj Chauhan, Warrior Hero of (Our) Land” (Dharti ka Veer Yodha Prithviraj Chauhan) aired between 2006 and 2009 on StarTV. A recent bronze statue of him forms the centerpiece of a large memorial park created in the king’s honor in 1996 at Ajmer, the city in the state of Rajasthan that was his dynasty’s capital. It is featured on the Wikipedia entry on Prithviraj Chauhan and appears on numerous other websites.

The main reason for Prithviraj Chauhan’s continuing fame is Prithviraj Raso, an epic about the king that became popular beginning in the late sixteenth century. In this poem composed in medieval Hindi, Prithviraj does not simply sink into obscurity after his defeat as most historians now believe. Instead, Prithviraj Raso tells us that the king was taken captive and blinded. Prithviraj’s loyal court poet, Chand Bardai, hears of his lord’s imprisonment in Ghazni, the enemy’s capital, and makes the long journey to Afghanistan. There he tricks Muhammad Ghuri into permitting an exhibition of Prithviraj’s legendary skill at archery. The blind Prithviraj, who is supposed to shoot an arrow through seven metal gongs thrown up in the air, instead aims at Muhammad Ghuri’s voice and instantly kills him. With this gratifying ending to his life story, the king regains his honor if not his kingdom. Although scholars have denied Prithviraj Raso‘s historicity for over a century, the claim that it dates back to Prithviraj’s twelfth-century lifetime is still sometimes made, especially in popular Indian culture.

The almost two hundred surviving manuscripts of Prithviraj Raso show that it was a favorite of the Rajput warriors of northwestern India. Rajputs were the main group of Hindus who fought on behalf of the mighty Mughal empire, most of whose leading officers were Muslim. Prithviraj Raso maintained its status as an authoritative source of information on King Prithviraj among Rajputs well into the nineteenth century. This was partly because James Tod, the first British agent appointed to their territory, accepted and propagated the Rajput belief that the epic was written by Chand Bardai, Prithviraj’s court poet. Rajput nobles of the early nineteenth century cherished Prithviraj Raso as a history of their community because the epic narrated the valiant deeds not only of the king but also of his 100 elite warriors, regarded by later generations of Rajputs as their ancestors.

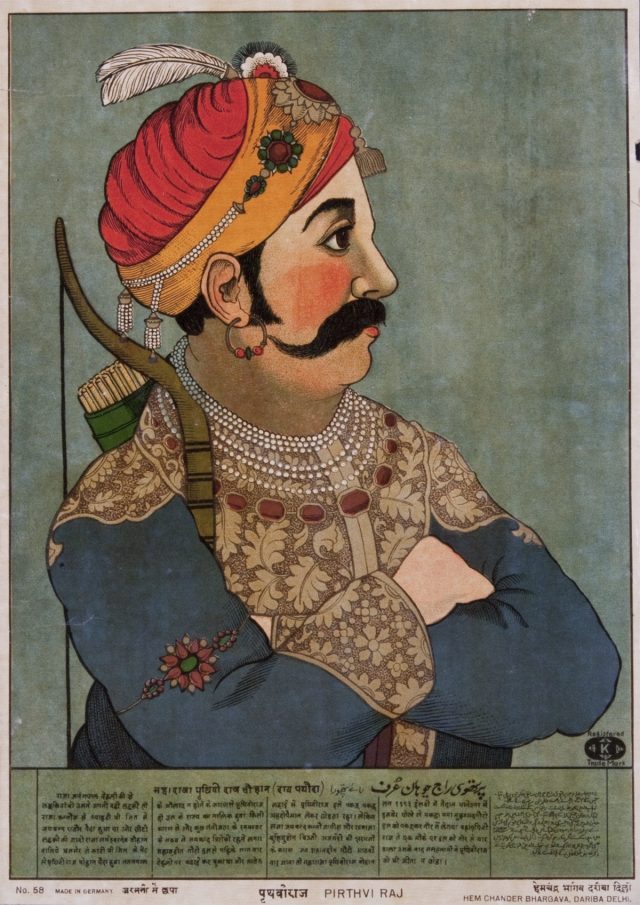

Once a sense of Indian nationalism developed in the late nineteenth century, after more than a hundred years of British rule, Indian intellectuals came to regard Prithviraj Chauhan as a patriot who had given up his life in the struggle against foreign invaders. Prithviraj Chauhan and other Rajput lords inspired colonial era Indians who also had to face foreign rulers, although they were English this time and not Central Asian. Prithviraj Chauhan was already confirmed as a nationalist, anti-colonial hero when Western scholarship rejected Prithviraj Raso‘s claim to be an eyewitness account of the king’s twelfth-century reign. During the early twentieth century, Prithviraj Raso‘s version of his heroic exploits was retold repeatedly in the newly expanding public sphere created by the modern Indian printing presses. He was even commemorated in visual form, on mass-produced lithographs like the example below from the 1930s. Throughout the period of the nationalist movement against British colonialism, therefore, the hero of Prithviraj Raso retained his grip on popular imagination and this image of the king has prevailed in popular culture since India’s independence in 1947 as well.

The long history of Prithviraj Chauhan and the popularity of epics like Prithviraj Raso shows the remarkable resilience of popular myths that can shape the ways kings are remembered in new historical contexts.

Adapted from:

Cynthia Talbot, The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Chauhan and the Indian Past, 1200-2000 (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Read more about Indian rulers and their stories:

Catherine B. Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India before Europe (2006).

This survey of Indian history provides an overview of developments from Prithviraj Chauhan’s death in the late twelfth century to the commencement of British dominance in the subcontinent. The time span it covers, the years from 1200 to 1750, corresponds generally with the period of Muslim rule in North India. It is particularly strong on cultural history.

Manan Ahmed Asif, A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia (2016).

The Chachnama has long been identified as an eighth-century chronicle about the Arab invasion of Sind, the southern Indus region of Pakistan. Because that was the first area of the subcontinent to be ruled by Muslims, this text was regarded as the forerunner of a long line of triumphant narratives about the Muslim conquest of South Asia. In his radical re-interpretation of Chachnama, Asif shows that it is actually a work of the thirteenth century which articulated a regional identity for Sind that situated it in a transnational world of commerce and travel.

James W. Laine, Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India (2003).

Laine, a scholar of religious studies, is interested in how the evolving narratives about the seventeenth-century Maratha king Shivaji contributed to the formation of a Hindu identity in the Maharashtra region during the past 350 years. Over time, Shivaji, whose armies successfully resisted the advance of the Mughal empire into the Western Deccan for decades, came to be associated with certain local saints and goddesses in popular memory. Laine’s questioning of some aspects of the stories surrounding Shivaji led to outrage among right-wing groups in Maharashtra and the banning of this book.

Ramya Sreenivasan, The Many Lives of a Rajput Queen: Heroic Pasts in India c. 1500-1900 (2007).

The Many Lives of a Rajput Queen also explores multiple narratives about a single figure and highlights their changing content over time. However, the focus of Sreenivasan’s study, Padmavati, is a woman who most probably never existed but whose beauty was reputedly the cause of Delhi sultan Ala al-Din Khalji’s attack on the famous Rajput fort of Chittor in 1303. As in the case of Prithviraj Chauhan, the story of Padmavati was retold by James Tod and subsequently taken up by Indian nationalists; and Sreenivasan attends closely to the shifting political contexts.

Top Image:

Prithviraj being dissuaded from going out in a storm while Kamdev, God of love releases arrows of desire and Laxmi and Narayan, rest on the celestial serpent ‘’Shesh nag’’: Mewar 17 century. Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur, Accession Number 17/11, 1097