It’s a three-hour, ultra-big-screen, deeply-researched box office mega-hit about… J. Robert Oppenheimer, project manager. Leslie Groves, the manager’s manager. Kitty Oppenheimer, the manager’s kids’ manager. Lewis Strauss, the wanna-be manager. Harry Truman, the buck-stops-here manager. James Byrnes, President Truman’s manager. The scientists of the Manhattan Project were thoroughly unmanageable. The bomb? It was everybody’s fault, and nobody’s in particular. Nuclear war by committee. It’s Oppenheimer: Destroyer of Responsibility.

Director and screenwriter Christopher Nolan isn’t wrong. The essence of the Manhattan Project, several characters remind us, was compartmentalization. The less any one project member knew about how to make an atom bomb, the less he or she could reveal to an enemy — especially a Soviet, an enemy of the Allied variety.

One of the movie’s smartest choices is to place the story of mankind’s first nuclear weapon in its ideological context. It excels at depicting the intellectual context, the scientific rivalries, and the egos surrounding the bomb. It deals tolerably well with the political context, the way World War II‘s messy wrap-up determined how the bomb was used. But where Oppenheimer sets itself apart from most other movies on the topic is in its depiction of the bomb as a turning point in the debate over communism: a debate that had raged for years and would only intensify as the nuclear era began.

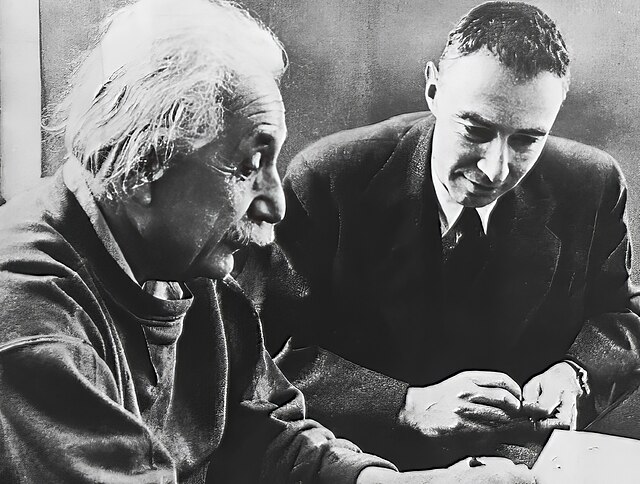

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

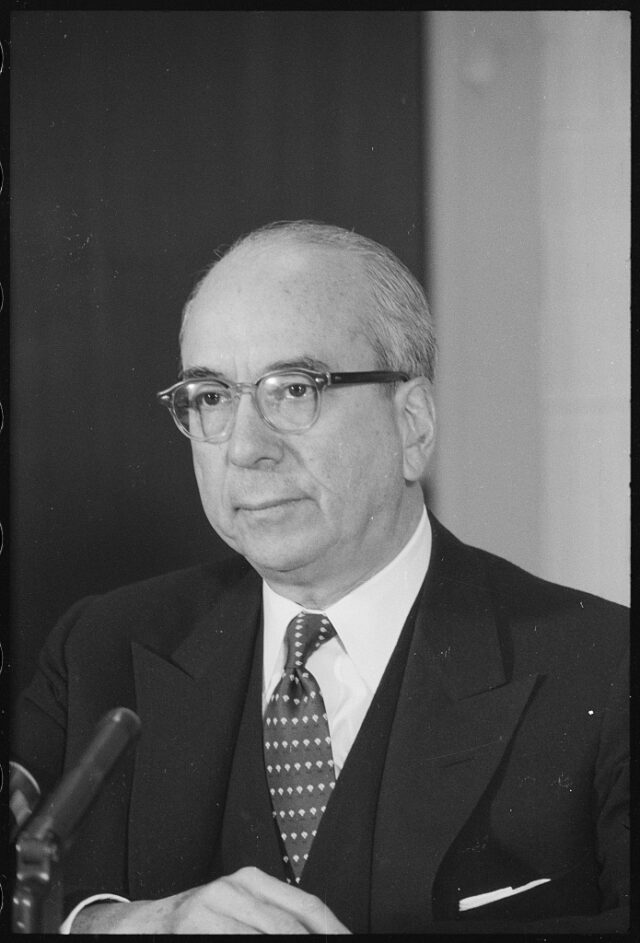

Around a third of the movie takes place many years after the bomb, when Oppenheimer’s (Cillian Murphy) security clearance is under review and his occasional colleague Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey, Jr.) is seeking Senate confirmation to join President Eisenhower’s cabinet. If this sounds obscure and more “inside baseball” than a gripping thriller, it is, and Nolan leans into its wonkiness with the confidence of a director who answers to no one. Unlike the rest of the movie, these flash-forward scenes are shot in black and white, a palette that cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema uses beautifully. Nolan, who is known for trippy time-bending films like Interstellar and Tenet, collapses about a decade’s worth of bureaucratic infighting into an interwoven, frenetic, emotional, and at times corny parallel movie that he grafts onto his more conventional biopic.

It is in this seemingly tacked-on portion of the film that the theme of communism vs. anti-communism stakes out its central position. The postwar rift between “the free world” of liberal capitalism and the opposing world of the communist bloc was dangerous because, after the bombs reached a certain strength, either side could have started the war to end all wars as well as terminating all known life. However, because that hasn’t yet happened (as of the publication of this article), Nolan has to illustrate the tension indirectly. While a McCarthy-era committee grills Oppenheimer and his wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) about their prewar communist sympathies, the bitter and conniving Strauss faces a divided U.S. Senate and a rebellion of atomic scientists.

The end result is two clear camps, Strauss’ and Oppenheimer’s. And in their pride and addiction to power, both ramp up pressure until the other is destroyed. Excessive makeup and monologuing from Strauss and unearned heroics from the Oppenheimers notwithstanding, this petty skirmish after the war is key to the movie’s message.

Oppenheimer reminds us that, if we seek the origins of the Second World War in the First, the people who lived it had a more recent and more relevant frame of reference: the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). This was the first major trial by combat between fascism on the one hand and communism and republican democracy on the other. It was the romantic struggle that drew in Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, and Casablanca‘s Rick Blaine. It was the proving ground for foreign, notably American, idealists who risked their lives or at least sent money to ensure that freedom – in the left-wing sense of progressive thinking and non-traditional living – would not go quietly into the night as Europe’s balance of power tilted sharply to the right.

Source: Library of Congress

Oppenheimer and his family and friends sent money through the robust international organization of the Communist Party. Nolan shows Oppenheimer as politically naive but stubbornly loyal to his communist girlfriend Jean (Florence Pugh) and fellow-traveling best friend Chevalier (Jefferson Hall). He also shows Oppenheimer’s support for unionizing and integrating academia, two supposed vectors for communist infiltration.

Nolan details how Oppenheimer’s politics made him a difficult pick to keep the U.S. military’s highest secret. Matt Damon’s character, General Leslie Groves, is a show-stealer as a buttoned-up, blunt-talking Pentagon man — the Pentagon man, since he was the one who built it — who forms a surprisingly close relationship with the Bhagavad Gita-quoting egghead he chooses for the job. Casey Affleck appears in one indelible scene as a hardened anti-communist who sees through Oppenheimer’s prevarications about his past. Nolan also shows how Oppenheimer and the scientists he recruited, a team that included a number of left-leaning academics and Jewish scientists, reacted to the realization that the atomic bombs would fall not on the Germans whose bomb program they’d been racing, but on a largely defeated Japan. Though the movie chooses not to show Japan at all, a scene in which Oppenheimer visualizes his Los Alamos team with Hiroshima- and Nagasaki-style burns is one of the film’s most powerful moments.

Oppenheimer dodges a real discussion of the surrender of Japan, about which whole movies have been devoted (see, for example, Japan’s Longest Day by Kihachi Okamoto). It mentions the Potsdam Conference, where Truman (Gary Oldman, in another instance of too much makeup) received Groves’s news about the successful Trinity Test, but viewers must read on their own about the conference’s significance for Japan’s surrender planning. He shows Byrnes (Pat Skipper), Truman’s Secretary of State and “Assistant President,” but conveys nothing about how the bomb changed Byrnes’ and, therefore, Truman’s thinking about the Soviet role vis a vis Japan. Relevant but outside the film’s scope are discussions about nuclear science in postwar Japan and the long shadow Hiroshima and Nagasaki cast over Japanese politics and art. These are directions the movie could have gone, but for Nolan the atomic bomb is not about Japan.

By the same token, the people who made the bomb are not defined by it. Oppenheimer emerges from the movie as an intellectual on par with the likes of Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) and Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh). He butts heads, always with the greatest professional respect, with Enrico Fermi, Edward Teller, Ernest Lawrence, and Werner Heisenberg, all brilliantly cast and sharply written. They all feel as though they could star in their own movies with the bomb as a mere footnote. The birth of nuclear weapons, it seems, was an almost accidental consequence of their combined genius. Their governments weaponized them, Nolan’s film tells us, and most of them had the good grace to feel uneasy about it.

Nolan’s is not a reductive kind of hero worship; these (almost) household-name scientists do, amazingly, feel like real people, and none are more flawed than Oppenheimer himself. The research that Nolan did to get these men right is obvious, and his Oppenheimer, like the real one, says that he feels blood on his hands and anxiety about the planet’s future. Yet equally obvious is the fact that Nolan sees the bomb-builders as visionaries, and if they felt they had no choice but to beat Hitler to the bomb, if they declined to take responsibility for what happened in Japan, then Nolan will go no further down those roads than they. What happened happened, now on to the Cold War.

Oppenheimer is Nolan’s second visit to World War II after 2017’s Dunkirk, and hopefully, it will not be his last. His understanding of the era — its mindsets, its cadences — is remarkable, and his handling of very big and very different personalities within the era is impressive. The film is his best-looking to date. There are beats that don’t work and paths not taken that deserved a closer look, but complex themes come through clearly and speak well of Nolan’s skills as a historian. Oppenheimer‘s success with audiences is a good thing well deserved.

But don’t miss Barbie, either.

David A. Conrad received his Ph.D. from UT Austin in 2016 and published his first book, Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan, in 2022. He is currently working on a second book, which will also focus on postwar Japan. David lived in Japan’s Miyagi prefecture for three years and can’t wait to go back to his home away from home.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.