by Brian Levack

Early in the morning on May 20, 1709, before the trials of offenders commenced, the judges of Scotland’s north circuit court in Perth pardoned some 300 men and women who had been charged with fornication or adultery. After granting these pardons, the court spent most of the day trying a case of incest that resulted in the conviction of John Martin, a 67-year old blacksmith from Dundee, and the acquittal of his half-brother’s 16-year old daughter, Elspeth Martin, for engaging in incestuous sexual intercourse.

The pardons and the trials of that day marked a turning point in the history of Scottish criminal justice. They brought about the de facto decriminalization of fornication and adultery in the Scottish secular courts while clarifying the Scottish law of incest and challenging prevailing male and clerical attitudes towards rape.

The pardons came about as a result of the passage of a bill of indemnity passed by the British parliament in the previous year. The union of England and Scotland in 1707 had resulted in the establishment of the United Kingdom and the creation of a single parliament for both England and Scotland. In this British parliament the English greatly outnumbered the Scots. On the face of it, the act of indemnity passed by parliament in 1708 had little to do with the prosecution of sex crimes. Its purpose was to pardon people accused of crimes in the wake of a Scottish rebellion against the British monarch, Queen Anne, in that year as a means of reconciling the Scottish population to the established regime. The statute extended a free and general pardon to subjects of the queen who had committed “all manner of treasons, misprisions of treasons, felonies, treasonable or seditious words or libels, misprisions of felony, seditious and unlawful meetings . . . riots, routs, offences, trespasses, entries, wrongs, deceits, [and] misdemeanors.”

Queen Anne in the House of Lords, Peter Tillemans (Wikimedia Commons)

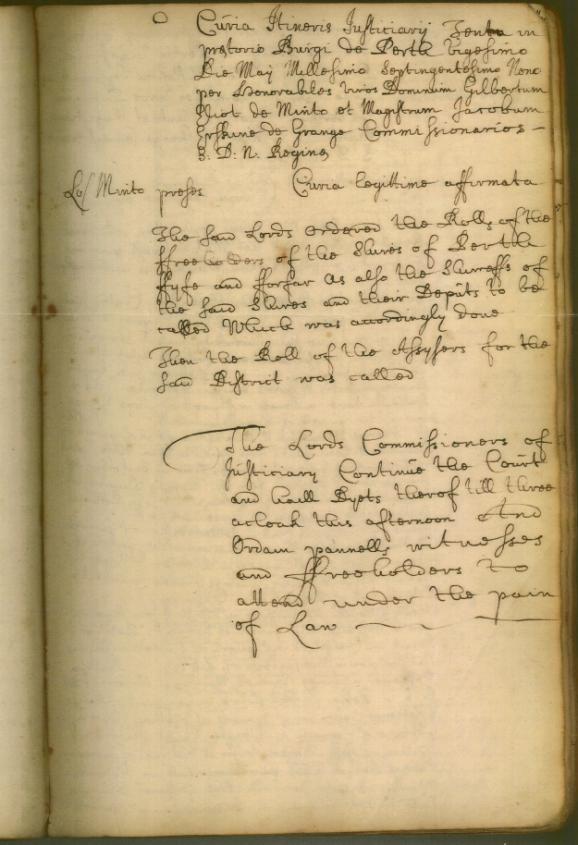

The Members of Parliament (MPs) who passed this bill of indemnity most likely never thought about its application to adultery and fornication, especially since neither of those offenses was a secular crime in England. But 300 Scottish offenders, whose names fill seventeen pages in the records of the court in the National Archives of Scotland, took advantage of this opportunity to avoid the penalties they would have otherwise incurred for these relatively minor sexual offenses. The judges of the court, who agreed that fornication and adultery should not be prosecuted, were happy to grant the pardons. After this trial, there were no more prosecutions in the Scottish secular courts for either offense.

Incest and rape, however, were considered much more serious crimes than fornication or adultery, and they had been specifically excluded from the bill of indemnity. Therefore the trial of John and Elspeth Martin for incest went forward. It is surprising that John was not charged with rape, since the indictment made it clear that he had forced his niece to have sex with him. The court had been reluctant to try him for rape because local magistrates and clergy considered Elspeth just as guilty as John for their sexual intercourse, presuming that she, like all victims of rape, had consented to this sexual act. The reason the court proceeded in this case was that sexual relationship between John and his niece had been incestuous. On that basis John was convicted. During Elspeth’s trial, however, her lawyer emphasized that John had used force against her. This led the jury to recognize that she was a victim of this sexual crime, not its perpetrator, and for that reason she was acquitted. By making the jury understand that rape was a violent crime against women and therefore the most serious of all sex crimes, Elspeth Martin’s lawyer contributed to a significant change in Scottish attitudes toward rape in the eighteenth century.