by Katherine Maddox

The city of Beirut witnessed a legendary amount of violence during the fifteen year long Lebanese Civil War. News programs the world over broadcast it into the homes of millions of people from 1975 till the Lebanese Parliament ratified the Taif accord in late 1989. Less well known is the reconstruction process that began in the Lebanese capital almost immediately after the war ended and which continues today. After commissioning but failing to implement an initial plan in 1992, the Lebanese government entrusted the reconstruction to Société libanaise pour le développement et la reconstruction de Beyrouth (Solidere), which was founded by then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, in 1994. Focusing primarily on the downtown area, the company sought to preserve what few buildings remained, create an international business district, and make a profit. As is the case with many urban reconstruction projects, Solidere’s plan was met with resistance and protest, especially considering the still-divided nature of Lebanese society. Therefore, Solidere took on the secondary task of defining and emphasizing an architectural heritage that could bridge the sectarian gaps inherent to Lebanon and thus Beirut.

News programs the world over broadcast it into the homes of millions of people from 1975 till the Lebanese Parliament ratified the Taif accord in late 1989. Less well known is the reconstruction process that began in the Lebanese capital almost immediately after the war ended and which continues today. After commissioning but failing to implement an initial plan in 1992, the Lebanese government entrusted the reconstruction to Société libanaise pour le développement et la reconstruction de Beyrouth (Solidere), which was founded by then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, in 1994. Focusing primarily on the downtown area, the company sought to preserve what few buildings remained, create an international business district, and make a profit. As is the case with many urban reconstruction projects, Solidere’s plan was met with resistance and protest, especially considering the still-divided nature of Lebanese society. Therefore, Solidere took on the secondary task of defining and emphasizing an architectural heritage that could bridge the sectarian gaps inherent to Lebanon and thus Beirut.

In his book commissioned by Solidere, Beirut City Center Recovery: The Foch-Allenby and Etoile Conservation Area, Robert Saliba provides an historic and architectural commentary to accompany the physical work undertaken by the company. Saliba, who is an Associate Professor of Architecture and Graphic Design at the American University of Beirut, has published extensively on colonial architecture in Beirut from the Late Ottoman and French Mandate periods, and was thus the ideal researcher to provide Solidere with the historic justification and explanation of their project. Like many of his other books, Beirut City Center Recovery is a multimedia visual study as well as a scholarly work. It traces the development of the zones around Rue Foch and Rue Allenby and Place de l’Etoile from their emergence and consolidation at the turn of the 20th century up to their current contested renovation. Like the reconstruction project he ultimately validates, Saliba must synthesize the diverse history of the Beirut Central District. Not only does he provide an historical account supported by archival images and maps, the last third of the book is comprised of comprehensive architectural surveys of the remaining historic buildings in both zones. With access to private collections, including Solidere’s own private archive, Saliba provides an unprecedented look into the history that informed Solidere’s plan.

Weighing in at five pounds, Beirut City Center Recovery could be deemed a “coffee table book” and indeed its strongest elements are its visuals, including haunting photos of downtown’s deserted streets taken directly following the Lebanese Civil War and after their reconstruction. No other book exists that so wholly addresses the often-disputed visual character of downtown Beirut. However, just as many critics of Solidere’s new downtown accuse the company of glossing over the legacy of the war, Saliba also neglects any real commentary on this chapter in Beirut’s history. Perhaps, as is the case with Solidere, Saliba wants the downtown area to transcend the sectarian conflict that divided the city for fifteen years. Since the book was published in 2004, Beirut has seen a war with Israel, the assassination of Rafic Hariri and many others, and the rise to power of Hizbollah. In light of this, Beirut City Center Recovery has become a historical artifact in itself, an optimistic presentation of a unitary space in a city, and a country, that is still very divided.

Photo credits:

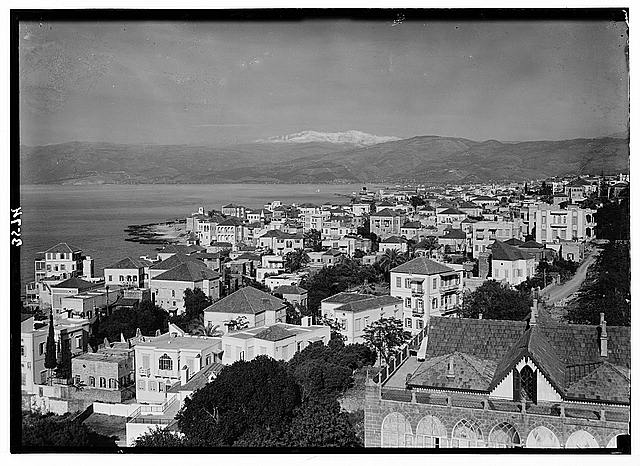

Unknown photographer, Beirut and St. George’s Bay. Showing snow-clad Sunnin

American Colony (Jerusalem) via Library of Congress

James Case, Beirut, Martyr’s Square, 1982

via Wikipedia

Check out the other winning and honorable mentions submissions for our First Annual Undergraduate Writing Contest:

Carson Stones’s review of Odd Arne Westad’s Global Cold War

William Wilson’s review of George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia

Lynn Romero’s review of Open Veins of Latin America