A major question among scholars of freedom and slavery in the Atlantic world concerns the extent to which Indigenous African characteristics were successfully transferred to the Americas and survived enslavement, a system of formalized debasement, and dominant European or American social and political systems. This sprawling question has generated intense academic debate. Published in 1976, Sydney Mintz and Richard Price’s The Birth of African American Culture: An Anthropological Perspective argued that the extreme hardships of the Middle Passage and enslavement profoundly shaped the lives of African and Afro-descendant communities in the Americas. This process of ‘creolization’, they contended, gave rise to entirely new cultures, distinct from their Indigenous African roots.[1]

Both schools of thought produce interpretations that hinge on an unquestioned acceptance of the principles of cultural syncretism that uncritically delineates ‘African’ and ‘non-African’ characteristics. More recently, James Sidbury and Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra have argued that such claims risk becoming increasingly meaningless. Instead, dominant historiographical trends are shifting to describe the early modern Atlantic world as a fluid landscape where change and cultural mixing were constants, challenging the assumption that one can draw a clear line between ‘African’ and ‘non-African’ characteristics. Scholars such as Brown, Sidbury and Cañizares-Esguerra, and Thornton use the backdrop of ethnogenesis, or the formation and development of ethnic groups, to investigate older arguments about the continuity or separation of African and Afro-descendant populations from their African roots. In this article I propose that the understudied indigenous African socio-political institution of the compound provides a useful lens to study the organization and evolution of African and Afro-descendant populations with a focus on 18th-century colonial Jamaica.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

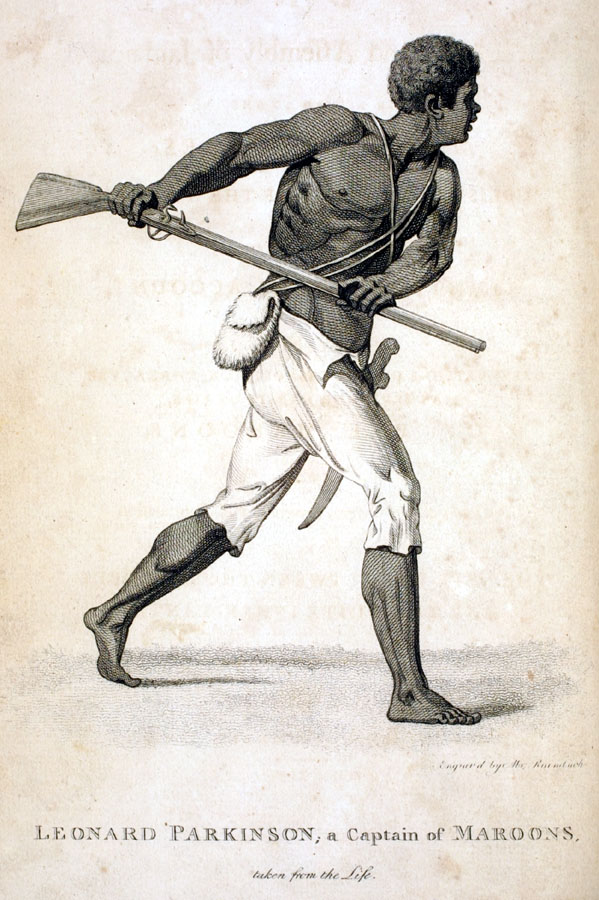

The study of the Indigenous characteristics of African and Afro-descendant populations in 18th-century colonial Jamaica is prominent in colonial and contemporary historiography. Scholars have focused particularly on Akan-speaking enslaved people transported from the Gold Coast in West Africa and who were known for their numerous and persistent acts of rebellion. Known as the Coromantee, among many other names, they were described by colonial writers such as Thomas Phillips, Brayan Edwards, W.J Gardner, and Edward Long as exceptionally strong, hardworking, rebellious, and warlike compared to other groups of enslaved people.[2] Most modern scholars recognize that African-born Akan-speaking groups composed the largest (albeit decreasing) demographic segment of the island during the 18th century, forming the so called “Coromantee nation.”[3] In Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War Vincent Brown argues that Jamaican slaves derived much of their leadership, tactics, and rituals directly from indigenous Akan-practices. However, this was a far from straightforward process.

Scholars have been focused on the ethnogenesis of the Coromantee as a tool for their organization and self-identification, and the degree to which this transformation represented a continuation or break from previous socio-political formations. However, through subsequent readings of scholarship on the discourse of ethnicity, major discrepancies in the study of African socio-political modes of organization appear. Few contemporary sources about slavery and ethnicity in Jamaica substantially analyze the complexity and contexts in which the socio-political characteristics of enslaved communities were originally and continuouslyproduced.

Modern historians like Vincent Brown, Robin Law, Simon P. Newman, and John Thornton widely accept that the “Coromantee nation” was originally an European invention: an amalgamation of diverse groupings of people that roughly (but not exclusively) corresponded to the Gold Coast that had no shared identity.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Crucially, these ‘non-African’ impositions seem to have been, at least partially, accepted by Akan-speaking slaves in the 18th century.[4] While the Coromantee remained far from a unified ‘nationality’ it is clear that some form of shared Coromantee identity developed in 18th-century Jamaica. This suggests the creation of a Coromantee identity may constitute an example of cultural syncretism, that is, the mixing of two distinct cultural elements to create something new: an epistemological creolization. More concrete examples of supposed Afro-European ‘cultural syncretism’ can be found in Alleyne Mervyn’s study of Jamaican linguistics and Erin Trahey’s analysis of kinship networks among elite freed women of color in Jamaica, where the island’s populations incorporated many elements of “European culture,” reflecting cultural creolization.[5] Such interpretations suggest that the incorporation of ‘non-African characteristics’ into populations previously considered ‘authentically African’ prior to enslavement creates something entirely new and removed from “the past.” [6] It is like the ship of Theseus: part by part, the African ship is replaced with new, non-African parts. All of this raises a question: At what point is the African ship no longer African but something else entirely?

How did African and Afro-descendant populations maintain continuity in the face of radical change in both Africa and the Americas through the socio-political institution of ‘the compound’?Qladejo O. Fadipẹ describes the compound as the smallest and most important political unit in Yoruba society.[7] The ‘compound’ derives from the Yoruba term, “agbo Ilé, (lit., a flock of houses),” which houses the “idile”[8] or family/clan, led by a baálė, the head of a compound, usually the eldest male relative of the founding lineage of a compound chosen by popular consensus from full compound-members.[9] Compounds, especially during periods of violence, might contain multiple extended families and dependents.

At its most basic level, the compound represents a complex set of unequal client-patron relationships producing vertical power structures where social and political standing was defined by one’s place in a steep but fluid hierarchy.Compounds contained dependents—clients—like children, wives, enslaved people, and refugees subject to the immediate and personal authority of a compound’s patron(s), like a baálė.[10] Each baálė oversaw the internal and external affairs of their compound, with few exceptions, acting as a bridge between compound members and the higher authorities within the community, thereby fostering stable political units.[11] Conversely, these vertical power structures existed within complex horizontal power networks containing thousands of other compounds organized into alliances and polities of varying size and sophistication.[12] They existed at the intersections of kinship, lineage groups, chieftains, village/town authorities, religious cults, and states, binding them all together.

The geography and violent landscape of pre-colonial West Africa, driven by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, fostered constant displacement and circulation of people, creating what James Scott refers to as “shatter zones” or areas where continuous waves of peoples settled into heterogeneous communities organized to foster mutual aid and protection. One example is Lagos, which was populated by numerous waves of different people.[13] Because the wealth and power of pre-colonial West African groupings were usually based on the control of people, its socio-political institutions developed to incorporate large numbers of diverse individuals.[14] To do this, compounds not only needed to operate in violent and chaotic areas but also overcome the cultural differences among their heterogeneous members. The key to doing so, according to Sandra T Barnes, was the incorporation of outsiders and outside knowledge.

In pre-colonial Akan-speaking communities, there was a potent desire to obtain and incorporate outside knowledge vis-á-vis the acquisition of foreign dependents, sometimes through violence. An example from Asante oral traditions is Gynama Nana, the Queen Mother of Takyiman, who was captured and taken to Kumasi as a enslaved person. Her granddaughter was later given a prominent role in the Asante state as the Abanasehene, responsible for the Asantehene’s clothes.[15]

Takyiman oral traditions argue that the introduction of Gynama Nana and other individuals from Takyiman was even more significant, supposedly “civilizing” the Asante Empire.[16] Even the more modest Asante account shows how Takyiman outsiders were brought into Asante society and incorporated into the households of prominent officials.

Another example is the case of Kramo Tia, which showcase the importance of outside knowledge in Akan-speaking communities. Kramo Tia was a gifted Muslim Imam from the polity of Gonja north of Asante. Asante oral traditions claim that Kramo Tia was captured by the Asante and made into a slave of the Asantehene because he was a “…powerful Kramo or Moslim who was gifted in the Koran and worked miracles…”[17] Conversely, Gonja oral traditions claim that the Asantehene invited Kramo Tia to participate in his court because the best Imams were said to come from Gonja.[18]

Both the Asante narrative and Gonja counter-narrative demonstrate how the Asante sought Kramo Tia’s unique outside knowledge. Like Gyamana Nana and her family, Kramo Tia, and his descendants gained prominent positions of power in Asante society because of their outside knowledge. This power was reinforced through Kramo Tia’s formation of a compound as shown through the accounts of Al-Hajj Sulayman, grandson of Kramo Tia.[19] Kramo Tia organized these enslaved people into a cohesive but heterogeneous community bound through shared bondage to Kramo Tia’s central lineage group.[20]

While the specific characteristics of compounds varied significantly, there were three important commonalities. First, compounds tended to be localized hierarchical institutions bound by varying client-patron relationships: vertical power networks. Second, compounds operated within complex networks of fellow compounds and other political formations such as towns, chieftains, or kingdoms: horizontal power networks. Together, compounds created flexible political relationships forged in chaotic environments, making the compound incredibly resilient. Third, the heterogeneous populations of compounds—attributable to the region’s endemic violence—made them unusually open to the incorporation of outside knowledge that produced change.

The compound was a remarkably adaptable institution, which accounts for both its enduring significance and the challenges in recognizing and studying it. Just as ethnic categories make complex groupings legible, the compound can provide a framework for understanding socio-political groupings across ethnic, state, kinship, and religious lines, binding these elements together. I suggest that the compound survived its forced relocation to 18th-century Jamaicabecause it incorporated heterogeneous populations and ideas into workable groupings that were able to operate within the brutal conditions of racial slavery. Thus, the reconfigurations observed in African and Afro-descendant populations in 18th-century colonial Jamaica should not be seen as a break from their pasts. Instead, these changes should be understood as continuations of a much longer process of transformation across the early modern Atlantic World.

In his article, The Coromantees: An African Cultural Group in Colonial North America and the Caribbean, John Thornton analyzes the ethnogenesis of the Coromantee, or the coming together of the Coromantee as a distinct and real ethnic, or “national” grouping in 18th-century colonial Jamaica.[21] Both Thornton and Vincent Brown agree that no widespread Coromantee identity existed in Africa, and argue that upon arriving in the Americas, heterogeneous Akan-speaking communities fostered immediate connections with fellow Akan speakers due to their shared language.[22] However, besides language, Thornton argues that there were “…no other common institutions that might have linked the linguistic group together.”[23] He points to the absence of indigenous political and religious homogeneity capable of fostering a pan-Coromantee identity. Instead of indigenous socio-political institutions, Thornton argues that a new and more flexible ethnic community emerged, forming a broad “super-family” known as the Coromantee nation.[24]

Source: Wikimedia Commons

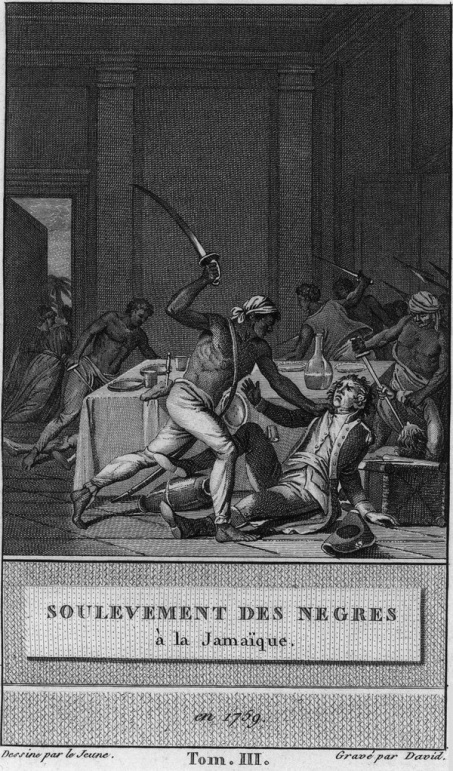

Connecting compounds on the Gold Coast to compounds in Jamaica requires an examination of the contexts and characteristics necessary for compound formation. As explored through the case studies of Gyamana Nana and Kramo Tia, Gold Coast communities existed in porous landscapes. Both individuals may have been forcefully brought into Asante society through violence. Kramo Tia and his descendants built his wealth and power by incorporating dislocated slaves into his compound. Brown further corroborates the endemic chaos of the Gold Coast, predisposing the region to compound formation.[25] Jamaica was similarly characterized by endemic violence and displacement from the slave trade and racial slavery.[26] This chaos was exacerbated during Jamacia’s frequent periods of warfare and armed insurrection, including Tacky’s Revolt (1760-1761).

Gold Coast and Jamaican groupings were highly heterogeneous.[27] DNA tests among modern Jamaican populations have traced significant numbers of their ancestors from Senegambia, Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast, the Bight of Benin, Bight of Biafra, West-Central Africa, Southeast Africa, and East Africa.[28] From the Gold Coast, the majority of ancestors were Akan speakers, though groups like Gā and Ewe speakers were also represented. Even among the Akan, colonial writers observed a high degree of diversity where many non-Akan populations around the Gold Coast adopted Akan as a regional lingua franca.[29]

Thornton cites several examples of non-Akan individuals integrating themselves into high positions of Coromantee “national associations”. In 1736, a prominent slave named Court, possibly of Gā origin, was executed after his public coronation as king of the Coromantees in Antigua.[30] Court likely possessed specialized leadership knowledge due to his high social standing in West Africa. He brought this knowledge into a new society as an outsider, and was able to obtain a high position of power. His story clearly mirrors that of Kramo Tia and his family/compound’s integration into Asante society.

Furthermore, during Tacky’s Revolt in colonial Kingston, Queen Akua was elevated to a high position of power by the city’s Coromantees. Her socio-political network, defined by reciprocal and uneven relationships, resembled the porous political structures of the West African compound, where loyalty, not territorial boundaries, determined the scope of her power.[31] Erin Trahey’s analysis of extended kinship networks among elite free women of color in Jamacia illustrate how localized socio-political patronage networks incorporated Euro-American characteristics.[32] Trahey uses Jamaica’s rich archival records, citing the will of Mary Gwyn to reconstruct the inner workings of Gwyn’s “kinship network”.[33] Gwyn’s socio-political network consisted of a complex web of horizontal “African-descended bonds of affection and affiliation” and a number of dependents (slaves) organized in hierarchical (vertical) manner. Many of the characteristics and contexts indicating compound formation are present in this case study.

However, the existence of Mary Gwyn’s compound and its authentic “Africaness” may be called into question by the Euro-American elements of her life. Gwyn made use of British paperwork and laws to secure the transfer of her property. She had an English name, likely spoke English and wore European clothing. It is unclear how Mary Gwyn identified herself and imagined her heritage. Each individual had a unique relationship with and conceptualization of their heritage.

In this article I have argued that the compound, an “originally African institution,” survived its reconfiguration in the Americas, particularly in Jamaica, and remained a crucial form of socio-political organization among African and Afro-descendant populations. This view challenges the perspectives of Burnard, Mintz, Price, and Thornton, who contend that these populations lost much of their indigenous characteristics due to Euro-American influences through slavery. While Thornton describes the ethnogenesis of the Coromantee as a blend of African and European epistemologies, Vincent Brown emphasizes the agency of the Coromantee, linking their organization to indigenous African practices.

However, without the compound, this view risks essentializing the identities and actions of these populations as either more or less ‘African.’ The compound’s flexibility allows for a more nuanced understanding of cultural adaptation and the continued agency of African-descended people. By examining these processes, this articles advocates for a more dynamic framework that critiques fixed notions of “Africanness” and “Europeness,” offering a broader lens through which African and Afro-descendant agency in the Americas can be explored.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Dr. Cañizares-Esguerra for the capstone undergraduate seminar he taught this fall of 2024. The course’s focus on reading each week academic monographs, book reviews, and/or primary source anthologies gave needed historical and historiographical contextualization about freedom and slavery in the Americas. Moreover, this rigorous coursework provided excellent training for navigating the discipline of history: the production of guiding historical questions, the examination of primary source evidence, the analysis of a field’s broader historiography, and finally the creation of unique and valuable historical interpretations. Dr. Cañizares’ emphasis on primary source material challenged me to incorporate tangible historical evidence into my analysis of prominent historiographical narratives, grounding my research. His extensive knowledge of slavery in the Atlantic World, and the fields in which these subjects are studied was incredibly stimulating and rewarding.

[1] Sidbury, James and Jorge, Cañizares-Esguerra. “Mapping Ethnogenesis in the Early Modern Atlantic.” The William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 2 (2011): 181.

[2] Other names for the Coromantee include (but by no means are exclusive to) Mina, Aminas, Coromantis, Koromantyn, Coromantin, and Cormantine.

[3] Quantifying the Coromantee population of Jamaica is a challenging task. DNA analysis evidence corroborates mainstream stances that Gold Coast populations were generally the most significant. Newman, Simon P., Michael L. Deason, Yannis P. Pitsiladis, Antonio Salas, and Vincent A. Macaulay. 2012. “The West African Ethnicity of the Enslaved in Jamaica.” Slavery & Abolition 34 (3): 394. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2012.734054.

[4] Information originally cited from: Public Record Office, London (henceforward PRO) Colonial Office (hencefoward CO), vol. 9, file 10 (hencefoward 9/10), Antigua Minutes of Council, 1 November 1737, “Negro’s Conspiracy,” fol. 67. Cited From Thornton, John. “The Coromantees: An African Cultural Group in Colonial North America and the Caribbean.” The Journal of Caribbean History 32, no. 1 (1998): 162.

[5] Erin, Trahey. “Among Her Kinswomen: Legacies of Free Women of Color in Jamaica.” The William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 2 (2019): 257-288; Alleyne, Mervyn ‘Language in Jamaica’, in The Language, Ethnicity and Race Readers, ed. Roxy Harris and Ben Rapton (London: Routledge, 2003); Peter L, Patrick. “Jamaican Creole: morphology and syntax.” A handbook of varieties of English 2 (2004): 407-438.

[6] Trevor, Burnard. “The Atlantic slave trade.” In The Routledge history of slavery, 2010.

[7] Qladejo O. Fadipẹ, and Okediji Olu Francis. Sociology of the Yoruba. Ibadan. UP, 1970, 97-117.

[8] Peel, John David Yeadon, and J. D. Y. Peel. Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba. Indiana University Press, 2003.

[9] Many of these newly arrived dependents: slaves, refugees or otherwise, may not be considered, at least initially ‘kin’ but may have partial membership within the compound nevertheless. Fadipẹ 105.

[10] Fadipẹ 117.

[11] Certain legal offenses committed by compound members, “were placed by custom outside his [the baálė’s] jurisdiction. These were murder, witchcraft, incest violation, and the communication to women of the secrets of the secret societies,” Fadipẹ 108.

[12] Fadipẹ 106 ; Peel 59.

[13] Sandra T, Barnes. “Ritual, Power, and Outside Knowledge.” Journal of Religion in Africa 20, (1990): 250.

[14] Sidbury and Cañizares-Esguerra 185.

[15] Takyiman was a polity northeast of Kumasi conquered by the Asante Empire in 1723. For more background information about Takyiman and its relationship to the Asante Empire, please reference, Kwuame, Adum-Kyeremeh. “The historical background to the Takyiman disputes with Asante.” African Journal of History and Culture 8, no. 5 (2016): 30-40; The Asantehene is the title given to the ruler of the Asante Empire; Dr. Alex Kyerematen: Interviewed by Prof. Ivor Wilks and Dr. Phyllis Ferguson, September 12, 1973, Kings College, Cambridge, England. This interview can be found in the Ivor Wilks, Conversations about the Past. Taken from African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade.16-17.

[16] Nana Kofi Biantwo: Interviewed by Eva L. A. Meyerowitz in 1945. Taken from Eva L. R. Meyerowitz, Akan Traditions of Origin (London, 1952) 43–44. Taken from African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade, 23-24.

[17] The stool histories excerpted here were collected by J. Agyeman-Duah and are now housed at the Manhyia. Taken from African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade, 24. Archives in Kumase, Ghana. These excerpts come from Glenna Case, Wasipe, 231–232. Cited in Glenna Case, Wasipe under the Ngbanya: Polity, Economy and Society in Northern Ghana. (unpublished PhD dissertation, Northwestern University, 1979), 231. Taken from African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade, 24-27.

[18] Wasipewura Mahama Safo II: Interview by Glenna Case with Mathilda M. Soale, February 14, 1976, Wasipewura’s Palace, Daboya. Cited in, Case, Wasipe. Taken from African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade, 25.

[19] Al-Hajj Sulayman: Interviewed by Thomas James Lewin, July 10, 1970, Kumase. Cited from, Thomas James Lewin, The Structure of Political Conflict in Asante, 1875–1900. Volume II – Asante Field

Texts (unpublished PhD dissertation, Northwestern University, 1974), 65–75. Taken from African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade, 27.

[20] Al-Hajj Sulayman 27.

[21] Thornton 169; Brown 102

[22] Brown 86-87, 90; Thornton 164-165

[23] Thornton 166.

[24] Thornton 166-169.

[25] Brown 92-93.

[26] Thornton 169.

[27] Al-Hajj Sulayman 27.

[28] Newman 385.

[29] Long 472; John Thornton, Africa and Africans in Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1680 (Cambridge, 1992), 184-92. Cited from Thornton 165; Robin Law, The Slave Coast of West Africa, 1550–1750: The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on an African Society (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 22–25.

[30] Public Record Office, London (henceforward PRO) Colonial Office (hencefoward CO) Vol 9 PRO CO 9/10, fold. 45, 51, 100-102. Cited from Thornton 170; According to Thornton, “The name Tackey, by which he [Court] was also known, is a name associated with the royal family in Gā-speaking Accra. The fact that he was considered to be of “considerably family” may reflect this heritage. See the table of Gā royal names, in Hart, Slaves Who Abolished Slavery, 12, 29 nn. 13 & 14. Hart’s sources for this table were interviews with Na Anowa Tackie, the Queenmother of the Tackie lineage,” Thornton 178, endnote 44.

[31] Long, History of Jamaica, 2: 455; Rucker, Gold Coast Diasporas, 155, 212, 213– 215. Cited from Brown 162.

[32] Trahey 263.

[33] Trahey 276, quoted from Will of Mary Gwyn, proved June 21, 1783, LOS 47, fols. 114–115 (“kinswom[e]n,” 114), RGDJ.