Whose classical traditions? That is the question implicit in the Classical Traditions in Latin American History conference that took place on May 19th and 20th in London. We convened to investigate the ways in which classical traditions endured in a region that is rarely associated with classical antiquity. These definitions are, by and large, the product of the northern European Renaissance and were established and developed in places like the Warburg Institute. Such understandings of the classics are so narrow that they explicitly exclude all of late antiquity and the descendants of these societies, namely, the medieval Arab caliphates, the Ottomans, and the low and high European Middle Ages. Is the global south in the Americas a rightful heir to the classical traditions as defined by the Warburg Institute? Given the questions and papers of this conference, it seems, the answer still is up for grabs.

Is a region whose systems of education forced Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, Ovid, and Virgil down the throats of preschoolers, highschoolers, sophomores, masters, and doctors for at least four hundred years a rightful heir to the legacies of the Greek and Roman classical ages? What are those legacies? I, for one, find classical Rome reproduced with far more fidelity in current conceptions of time, space, hierarchy, labor, family, the sacred, and community in Quito, my home town, than in London, where I am visiting for six months. Every day.

Is the Christian culture of late antiquity part of the classical traditions? Do systems of education that held Origen, Jerome, Augustine, and Ambrose as intellectual giants qualify as rightful heirs to the intellectual values of classical Rome and Greece? What are those values? Do the Franciscan, Augustinian, Dominican, and Jesuit inheritors of the radical Aristotelian materialism of the twelfth-century university scholasticism of Aquinas, Dun Scotus, and William Ockham qualify as rightful heirs? Do the tens of thousands of youths trained for 300 years at the universities, academies, and courts of Lima and Mexico (and at dozens of other colleges and universities throughout Spanish America) in scholastic realism and nominalism, the Justinian code, and the Decretales, that is, the Corpus Iuris Commune and the Corpus Iure Canonici, qualify? Do the Mompoxiano (Mompox, Cartagena de Indias) Juan Suarez de Mendoza and the political culture he embodied in the mid seventeenth-century Spanish Monarchy qualify?

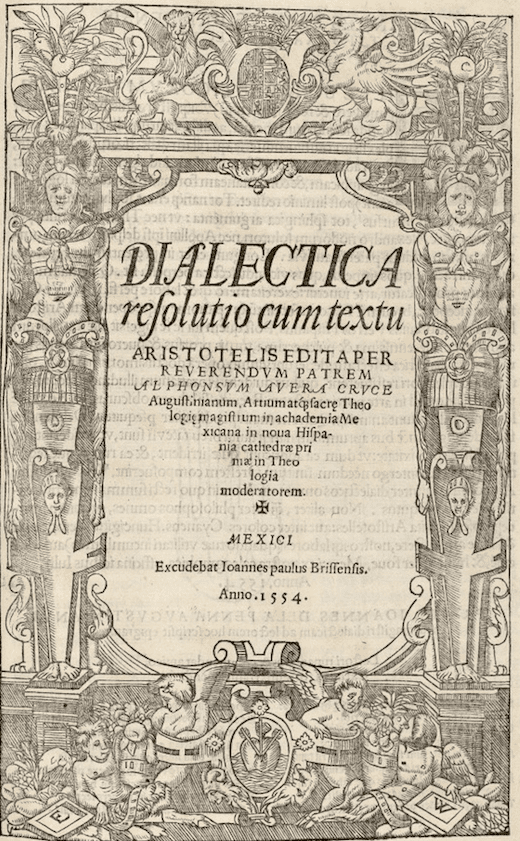

Suarez de Mendoza was one of the most renowned publici iuris Caesarum Professoris in Salamentesi Academia. He was also the author of the most influential European text in classical Roman tort and property law, his Commentarii ad Legem Aquiliam, published in Salamanca in 1651 and reissued in Lyon and Ambers all the way into the late eighteenth century. Suarez de Mendoza dedicated his work to the Count of Castrillo, the President of the Council of the Indies. Suarez de Mendoza saw himself as a Roman Senator wearing togas in Madrid’s academies and amphitheaters, helping administer an empire larger than Rome’s. But Suarez de Mendoza was not a fluke. Andrew Laird’s paper cites the cases of the Augustinian Alfonso de la Veracruz and the Jesuit Antonio Rubio, whose commentaries on the Logic and Physics of Aristotle penned in the mid and late 16th century at the University of Mexico became textbooks for European liberal arts colleges and universities. Veracruz and Rubio, however, were originally trained in Salamanca and Alcala. Andrew therefore forgets to cite the case of those Peruvians and Nuevo Granadinos who were actually trained at local universities and whose Latin texts in logic, ontology, theology, and jurisprudence became standard textbooks all over Central and Western Europe, as well as Goa and Manila. Andrew is not alone in that forgetting.

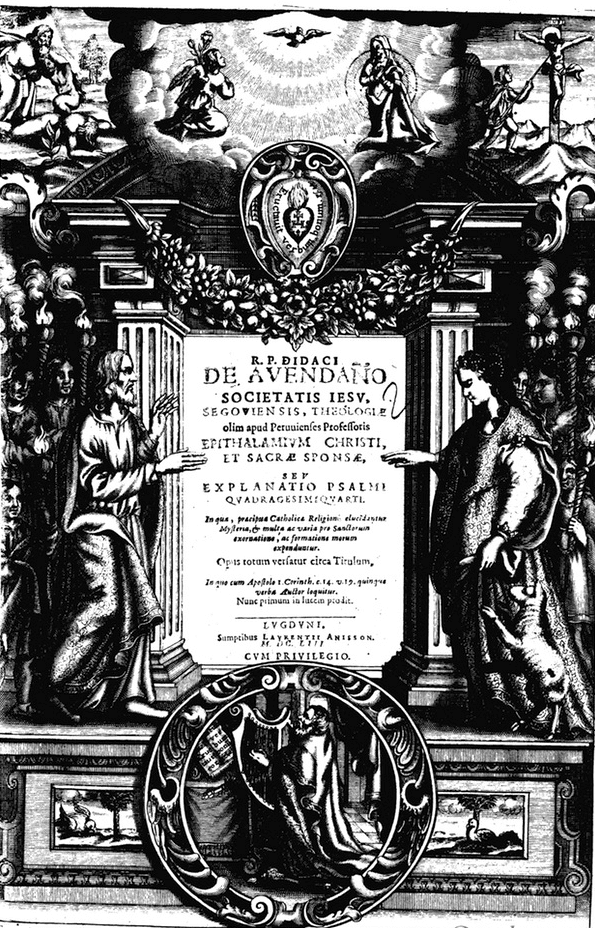

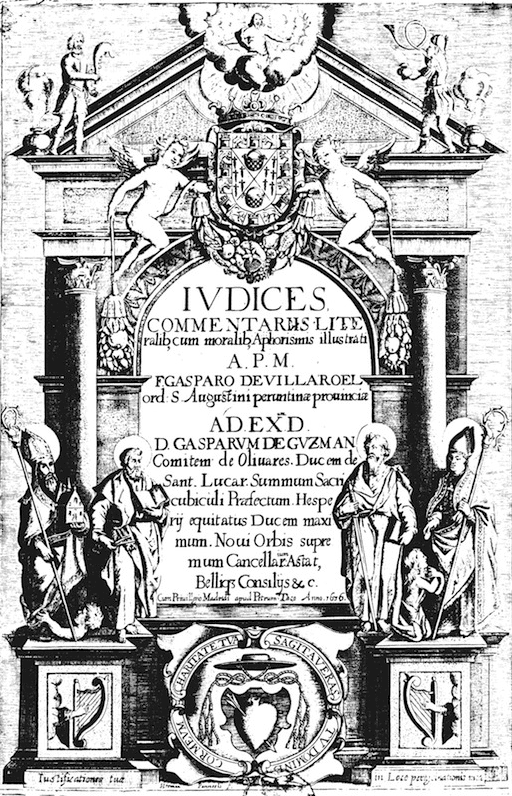

For a moment consider some of these long forgotten figures. Gabriel Alvarez Velasco, a Nuevo Granadino from the small college-town of Tunja, whose Latin texts on the rights of widows, orphans, and the downtrodden, De Priviliegii Miserabilium, became the standard European textbook on the legal privileges of miserable (His Judex Perfectus and his Epitoma de Legis Humana were also European bestsellers for some 100 years). Or consider the case of the Riobambeño brothers Alfonso and Leonardo Peñafiel who competed with Francisco Suarez to be the most influential 17th century Jesuit logicians, philosophers, and metaphysicians in the global Jesuit order. The Peñafiel bothers’ countless texts (including the multivolume Cursus Integri Philosophici , the Disputationes Scholasticae et Morales, and the Disputationem Theologicarum) moved endlessly from the printing presses of Antwerp, Cologne, and Lyon into the Jesuits colleges of Goa, Sri Lanka, Manila, and Prague. Or take the case of Diego de Avendaño, educated in Cuzco, who became one of the most influential and original European canonists of his generation. He was also one of the most influential European scholars on Aristotle and a leading biblical exegete. His exquisite commentaries on Psalm 44 and 88 were printed in Lyon and Antwerp in 1653 and 1668 respectively under the provocative titles of Epithalatium Christi and Sancta Sponsae (the wedding of Christ and his pious wife, the church) and Aphitheatrum Misericordiae (the global manifestation of Christ’s Mercy). Avendaño’s biblical scholarship can only compete with that of another son of the University of San Marcos, Lima, the Augustinian Gaspar de Villarroel. Villarroel’s 1636 Madrid typological and literal interpretation of the Book of Judges, Ivdices Commentariis, was based on the four different versions of the text: Greek (Septuagint), Latin (Jerome’s vulgate), Hebrew (Masoretic version) and the Aramaic Targum. This was one extraordinary Limeño Jerome.

Villarroel was born and raised in a society entirely invested in his scholarship and that in return made him Bishop of Chile, Arequipa, and finally Charcas (the seat of the silver mines). Peru did not hesitate for one second, unlike the University of London, to channel millions to sustain institutions of humanist learning like the University of San Marcos. Authorities used treasure that came straight from the forced labor of miners in Potosi and Huancavelica. By mid-17th century, San Marcos had a roster of 150 Masters and 100 PhDs educating a community of 1,500 students in the liberal arts, theology, jurisprudence, and medicine. This was the epitome of the classical world: an academy of hundreds of philosophers built on the back of a vast pool of Andean quasi slaves (and free labor too). Then again, it took an empire for the Warburg Institute to emerge.

The question addressed at this conference should be not whether there were “classical traditions” in Latin America, but whether these obvious classical traditions can be questioned out of existence or ruled out as completely marginal to the concerns of the millions of the illiterate and marginalized poor. The three papers under discussion make obvious how deep the classical traditions ran in the cultures of colonial and 19th century Spanish America. Andrew Laird maintains that it was the language of Aristotle’s polity, natural slavery, and barbarism that Spanish clerics and academics used to imagine theories of colonial legitimacy and sovereignty. He argues that it was the language of Lucian’s Saturnalia that allowed the magistrate and bishop Vasco de Quiroga to articulate a vision of two separate legal republics, one Indian and one Spanish. And that it was the language of Cicero (but also of Virgil and Plutarch I might add) that local Mexican academics used to counter the condescending views on the natural forces in, and the alleged dearth of academic institutions of, the Indies, both views held in tandem by European humanists and Neo Latinists like Joseph Justus Scaliger and Manuel Marti. Andrew forgets to cite the influential views of the Flemish humanist Justus Lipsius, whose inability to even consider institutions of learning in Spanish America caused members of the university of San Marcos like Diego de Leon Pinelo and the Franciscans brothers Salinas y Cordova to create genealogies of local academic excellence (see, for example Pinelo’s Hypomnema Apologeticum Pro Regali Academia Limensi, 1648) . These mid seventeenth-century Limeño accounts were not unlike those created by Eguiara y Eguren (see Biblotheca Mexicana sive Eruditorum Historia Virorum, 1755) in mid eighteenth-century Mexico to counter the patronizing views of Manuel Marti.

Nicola Miller, Erick Culhed, and Andrew Laird make explicit that it was the language of Roman republicanism and Greek aristocratic democracy that local learned elites deployed to endow their cities, patrias, and nations with vibrant moral genealogies. Nicola argues that it was the language of Roman republican resistance to tyranny that allowed marginalized popular black poets like Gabriel de la Concepcion Valdes, aka Placido, to wax lyrical against the tyranny of racism in mid-19th century Cuba. Erick maintains that it was the language of decadent imperial Byzantium that allowed late nineteenth century poets like the Puerto Rican Jose Jesus Dominguez, the Cuban Augusto de Armas, and the Nicaraguan Ruben Dario to invent a pan-Latin (Franco- and Hispanophile) culture of literary modernism. Ranging from popular to elite culture, from the Caribbean to Central America, and from the 1500s to the 1900s, the evidence is overwhelming: there were many, vibrant classical traditions all over Spanish America.

Why have these muscular traditions failed to constitute a narrative of a deep-rooted classical culture in Latin America? Weren’t these traditions in Latin America as deep and as significant as those of, say, Italy, Germany, or Britain? And yet my question for this audience goes much deeper: Why have classicists, and the Warburg Institute in particular, rarely looked at the global South to ponder whether the European humanist traditions might have been shaped by the “Latin American” learned communities I have briefly reviewed?

The scholarship on early modern humanism, recognized and celebrated by the Warburg, has painstakingly explored the impact of the indigenous peoples of the Americas on the creation of the Renaissance, itself a variety of many possible classical traditions. This scholarship has studied how Columbus and Luther brought into the glossaries, commentaries, and exegeses of ancient books the new worlds of geography and theology. In this type of scholarship, it is the Indian “savage” (demonic or noble), not the Spanish American Latinist, who is summoned as a heuristic device. It is time, however, to consider new genealogies for Europe’s early modern scholarship. In short, I am pleading, in Kant’s parlance, for a Copernican Revolution.

I have suggested that the classical tradition of seventeenth-century Spanish American academies and universities was so muscular that it shaped the classical traditions of Europe itself. We have yet to explore the impact that Nuevo Granadinos like Alvarez Velasco had on the European jurisprudence of distributive justice. We have yet to explore the role of Indianos like Suarez de Mendoza in the early modern transformation of property law. We have yet to ponder the influence of the mid-seventeenth-century professor of theology at the Royal University of Mexico, Juan Diaz de Arce, whose Opus Studioso de Sacrorum Bibliorum, book four of his massive two-volume treatise, Quaestionarii Expositvii pro clariori inteligentia Sacrorum Bibliorum (1647-48) was printed separately in Rome in 1750. Opus Studioso became influential with the Catholic curia at the height of the Catholic Enlightenment. Opus studioso was a bold argument on the epistemology of popular prophecy and the centrality of the illiterate in biblical interpretation. It is perhaps time to explore the significance of the Cuzqueno-educated Avendaño and the Limeño-educated Villarroel on biblical philology and exegesis, not only in Salamanca and Alcala but also in Antwerp and Lyon.

In a world of changing demographics and globalization, I suggest the Warburg Institute would greatly benefit from becoming curious about how Peruvian and Mexican traditions of classical scholarship transformed Italian, French, and German ones. For all the richness and oddities of the Warburg’s holdings, there is not a single copy in the library’s stacks of the works of Diego de Avendaño, Gaspar de Villarroel, Juan Suarez de Mendoza, Adolfo and Leopoldo Peñafiel, Gabriel Alvarez Velasco, and Juan Diaz de Arce. In fact, the Warburg holds not a single copy of the hundreds of texts penned by dozens of Spanish American Latinists that were printed in the presses of Rome, Cologne, Antwerp, Lyon, Prague, and Mainz throughout the long seventeenth century. The Warburg does not even have the token of all libraries with humanist and neo-scholastic collections, namely, the many commentaries on Aristotle by Antonio Rubio, the great “Mexican” metaphysician whose views Rene Descartes sought to slay. It is time to summon back the iconoclastic rebellious spirit of Aby Warburg. I am sure he would have enjoyed the work of Juan Diaz de Arce, that Mexican Latinist who like Warburg revered the epistemological authority of the illiterate.