by Kristopher Yingling

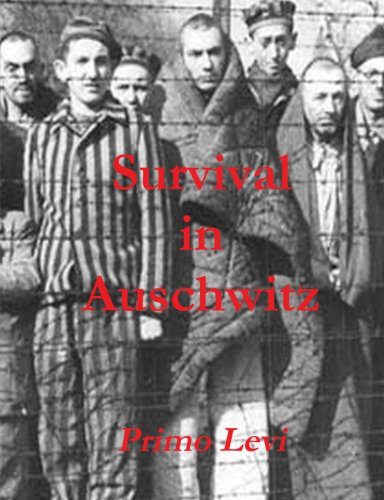

In Survival in Auschwitz, Primo Levi depicts a life where, under the severe conditions of hunger, cold, illness, and constant fear, men are transformed into beasts, and where justice and morality become insignificant in the fight for survival. Upon entering Auschwitz, families are separated and immediately hundreds are sent to their deaths. Tattooed and given their new identity of serial numbers, many forget their own past and their names.

Initially, Levi accepts his imminent death as everyone emphasizes that the only exit from Auschwitz “is by way of the chimney.” But for the next year, Levi learns to live pragmatically and efficiently under the Nazis’ continuous brutality. In doing so, he discovers two very different reactions from living in Auschwitz: those that are “saved” and those that are “drowned.” The drowned rarely exist in normal society, but in Auschwitz, they are everywhere. For many, the constant cruelty dehumanizes them to the level of animals, where men accept their fate and work themselves to certain death. Conversely, a few manage to push back and use their strength, intelligence, and patience to fight relentlessly within themselves against Nazi enslavement. It is only this perspective that gives men the determination and mental fortitude to survive.

Eventually, the prisoners worked their bodies to such desperate conditions that every man fended for himself. Friendships were based on pragmatism and selfish interest. Faced with utter solitude, many prisoners would lose all motivation for survival. Out of the thousands that entered Auschwitz weekly, only a few hundred would survive. These usually included the most valuable of prisoners, such as doctors, tailors, and shoemakers. Levi and many other camp veterans understood this and reacted to make themselves appear useful and not to drown in their detestable conditions. In doing so, the saved depended on the “underground art of economizing on everything, on breath, movements, even thoughts.” In the process, Levi witnesses how this strategy often leads the saved to social savagery and how “the struggle for life is reduced to its primordial mechanism.”

Jews from the Carpathian Ruthenia region arrive at Auschwitz, May 1944 (Image courtesy of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

Auschwitz represented a period of incomprehensible extremes, where the terms hunger, “tiredness, fear, pain,” and winter do not characterize their normal, societal notions. Levi “entered the camp like all others: naked, alone, and unknown.” However, he quickly learned the importance of defiance. By maintaining his humanity and individualism, he avoided becoming part of the drowned anonymous mass of beings marched into the gas chambers. Shipment after shipment, men worked themselves to death in silent desolation. But for Levi, these men had already died. Their names and memories left this world the moment they arrived. Through the crematorium’s smoky black ash their existence was forever forgotten, never even known by the few who witnessed their fate. Fortunately for Levi, rescue came before his breaking point. However, towards the end, even he showed signs of the “drowned.” As French prisoners tell Levi of the German’s retreat, he “no longer felt any pain, joy, or fear.” By now, it was only a matter of fact.

And be sure to check out Adrienne Morea’s honorable mention submission to Not Even Past’s Spring Essay Contest.