As one of the students in my U.S. women’s history class put it, “Women are just like men; except that they are different.” For all that men and women have had in common these many millenia, women’s experience has often been different. Women’s History Month gives us the opportunity to talk about two new and one not so new “good reads” on the subject.

The University of Texas Press has just published the latest from the impressive authorial team, Judith McArthur and Harold Smith, faculty at the University of Houston-Victoria. Texas Through Women’s Eyes: The Twentieth Century Experience (2010) begins with “Social Reform and Suffrage in the Progressive Era, 1900-1920,” discussing the civic reforms pursued by white and black clubwomen, labor activism, settlement houses and prostitution districts, and the state woman suffrage campaign.

Texas suffragists were among the few southern suffrage associations to win partial voting rights for women before the federal amendment was passed. These Texas women pulled a “fast one,” and you will want to read about it.

McArthur and Smith continue through the Great Depression, World War II, the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Rights Movement, and the backlash to same in the last decades of the twentieth century. They make the history they reveal personal with selected documents like “Hallie Crawford Stillwell Gets a Sink and Builds a Bathroom,” “Jessie Daniel Ames Urges Women to Vote against the Ku Klux Klan,” “Army Nurse Lucy Wilson Serves in the Pacific Theater,” “Ceil Cleveland Becomes a Teenage Bride in the Fifties,” and “Ann Richards Moves from Campaign Volunteer to County Commissioner.”

McArthur and Smith are also the coauthors of Minnie Fisher Cunningham: A Suffragists’ Life in Politics (2005) which won the Liz Carpenter Award for Research in the History of Women from the Texas State Historical Association and the T.R. Fehrenbach Book Award from the Texas Historical Commission.

Christine Stansell, a well-regarded historian at the University of Chicago, provides a national perspective in her latest publication,The Feminist Promise: 1792 to the Present (2010). Don’t be daunted by the title. This is not a polemic, nor is it a weighty treatise on social theory. Rather, it is an exceptionally readable narrative of the efforts of American women to improve their social, political and legal situation. Stansell notes the efforts of women of color and of working class women alongside the more well-known white middle-class activists. She provides the general reader, as well as the scholar new to women’s history, with a splendid survey of women’s rights activism beginning with the days of the early republic. Her discussion of the woman suffrage movement is particularly strong because she explains the divisions in the movement and its culminating diversity, which led to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. From the racism of the movement’s “southern strategy” to the dramatic protests of the National Woman’s Party in front of the White House even during World War I, Stansell’s unflinching history is good reading. Stansell barely pauses once women have won the vote. Her story continues through the interwar years to the “second wave” of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s.

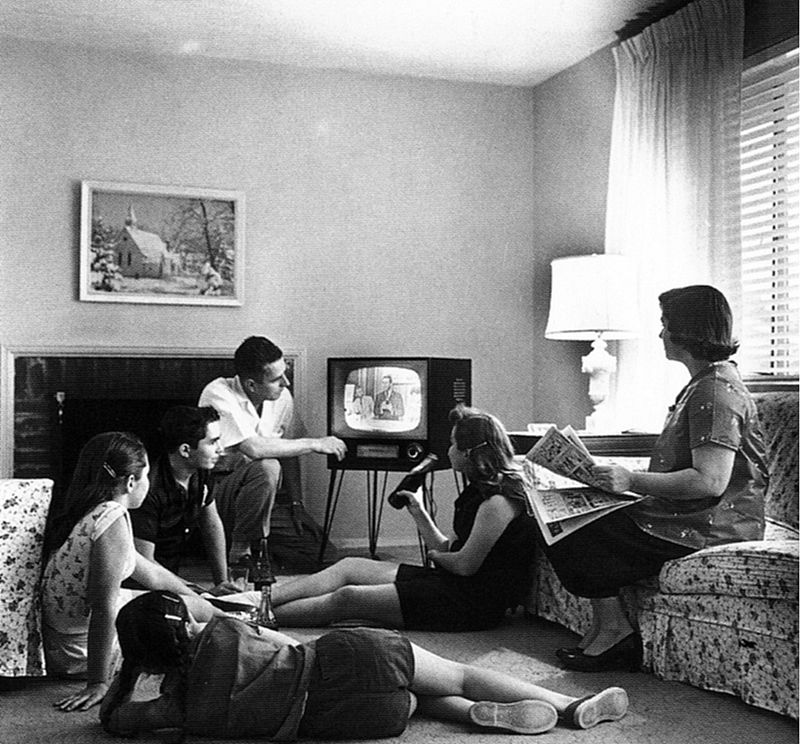

Again, she explains that the “movement” was far from monolithic in goals or tactics, but she acknowledges the accomplishments as well as the internal politics.Stansell’s subject is organized women’s activism, which like activism of all sorts, was viewed with suspicion in the early years of the Cold War, aka “the McCarthy Era.” Fortunately, Elaine Tyler May moved into the breach with Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (1988). Who knew that Cold War foreign policy and its home front counterpart had such important implications for family life? May’s first chapter “Containment at Home: Cold War, Warm Hearth,” shows the ways that the Cold War foreign policy of “containing Communism” was reflected in family life.

The Fifties have been canonized as the nostalgia decade of domestic tranquility before the tumultuous Sixties. Professor May confounds, or, at least complicates, this happy myth. The frenzied public celebration of family life introduced new stresses into families and to couples, as social norms regarding dating, birth control, marital sexuality, consumerism, and divorce were in flux. A history of family life, a history of women’s experience, Elaine Tyler May’s Homeward Bound is a young classic.

Photo credits

Suffrage Hikers, By Richard Arthur Norton, via Wikimedia Commons

Bessie Colman, First African-American Pilot, National Air and Space Museum, via Wikimedia Commons

Family Watching Television, 1958, by Evert F. Baumgardner, via Wikimedia Commons

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.