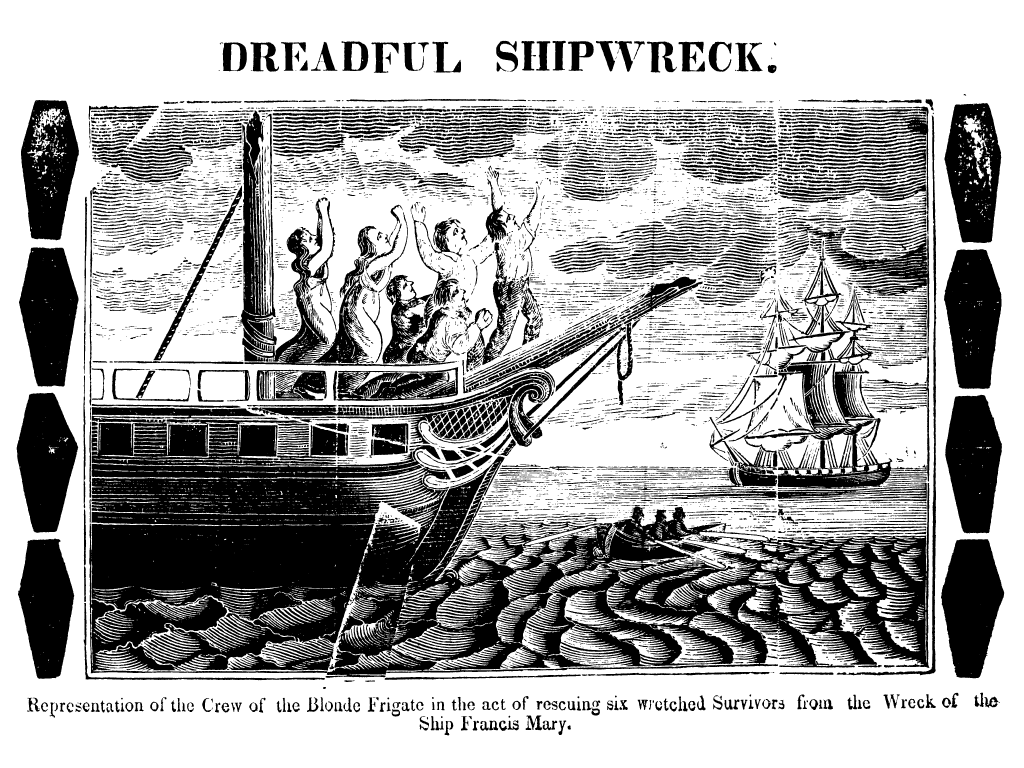

On March 7th, 1826, HMS Blonde rescued six emaciated survivors from the wreck of the Frances Mary. They included two women: the captain’s wife and Ann Saunders, a young woman hired to serve her. They had spent twenty-two days adrift, crowded in the main top of the half-submerged wreck, kept afloat by its load of timber, with only ten days of food and water. Six of sixteen survived. But they did so by resorting to cannibalism. Amidst this horror, Saunders, with “more strength in her calamity than most of the men,” transformed from working passenger to a key provider.[1] When her fiancé, James Friar, who had also worked aboard for passage, died, Saunders “shrieked a loud yell […] cut her late intended husband’s throat, and drank his blood, insisting that she had the greatest right to it.”[2] Ann Saunders kept two sharp knives in her monkey jacket – at every death, bled, cleaned, and carved – and kept those who remained alive. Without the women, the Morning Chronicle reported, some of the men would not have survived.[3]

Maritime life, especially in places like Europe or the United States, has been the subject of much mythologizing. From Cooper to Conrad to today’s Pirates of the Caribbean, fiction has familiarized audiences with creative tropes, contemporary stereotypes, and sometimes suspect ‘common knowledge’ of the maritime world of the past. These include ideas like “women and children first,” the drunken jolly Jack Tar, with a sweetheart in every port, and the belief that women were bad luck on ships. Maritime historians have spent decades investigating, and for the most part, debunking these myths, in an effort to differentiate between the stories we tell and the realities of maritime life. In the nineteenth century, when many of these myths solidified, the maritime world was at once practical, a real engine of economic and imperial life, and an idealized and mythologized cultural keystone of the national self-image. Every maritime myth presents us with two important questions: how true is the myth itself, and why was the myth perpetuated?

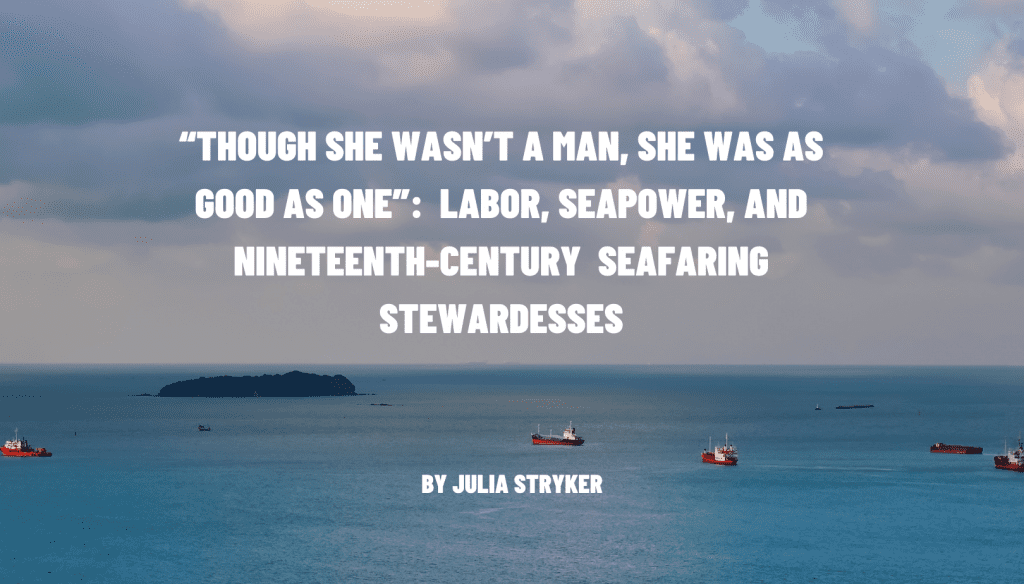

My research examines women working at sea. I push back against the idea that life at sea was exclusively a masculine domain, a false notion that has all but wiped-out the history of women’s seafaring labor. In the nineteenth century, women not only went to sea in ever-increasing numbers, but in increasingly professionalized positions as seafarers. Women, in other words, gained a recognized and appropriate place aboard ships.

Women are present at sea, and often overlooked in stories otherwise well-known. In 1908, when Violet Jessop interviewed for a position as a ship’s stewardess, the hiring agent at first had misgivings: “I was far too young, they generally took officers’ widows, and then again, I was too attractive”. She got the job.[4] To make her “attractiveness as inconspicuous as possible without losing zest in life” Jessop and her mother compiled a “man-frightening wardrobe.”[5] Four years later, early on the morning of April 15th, 1912, she found herself in perhaps the most famous shipwreck of all – the Titanic. Jessop again confronted an unsuitable wardrobe. She recalls saying to Stanley, a bedroom steward, as he “brought forth my new spring outfit, all trimmings and things. ‘That’s no rig for a shipwreck, all fussed up and gay.’ Suddenly I was trying to be jocular, afraid if I wasn’t I might cry.”[6] Though trying to maintain calm for both the passengers and their own sakes, it was hard to believe the Titanic was sinking. As she left the room, she called for Stanley to follow soon. In fact, it was the last she would see of him, “he was standing with his arms clasped behind him in the corner where he usually kept his evening watch. He suddenly looked very tired.”[7]

Women could be found at sea in newly professional positions. But defining those positions cut off the many liminal, indeterminate, and often invisible spaces in which women had previously worked. What changed between Saunders and Jessop was not the sudden sense that women belonged in certain places on ships, but the way labor was hired, managed, and bureaucratically surveilled.

There is a basic paradox here. Why, even as women grew ever more present, did the idea of their presence grow ever more antithetical to seafaring culture? This paradox is at the center of my research.

The answer lies, I believe, in the complex interactions between society, technology, and culture. It has implications for the very foundations of the Britain’s nineteenth-century empire, but it begins with finding women working at sea. For reasons both practical and prejudicial, histories of women at sea have focused on, the exceptional and the elite: officer’s wives, cross-dressed cabin boys, wealthy women travelers, female pirates, and victims of disaster. As Jo Stanley notes, however, “a celebratory over-focus on exceptional ‘heroines and hellions’ of the sea throughout world history highlights the need for grounded, contextualized studies in which scholarship is not sacrificed in the understandable excitement at finding missing women.”[8] Surviving remarkable wrecks saved the stories of Jessop and Saunders for posterity, but there is more to them than a shared acquaintance with disaster – they represent two ends of a century-long evolution in the relationship between gender, labor, and seapower, which reveals the multiple mythologies underpinning our understanding of the past.

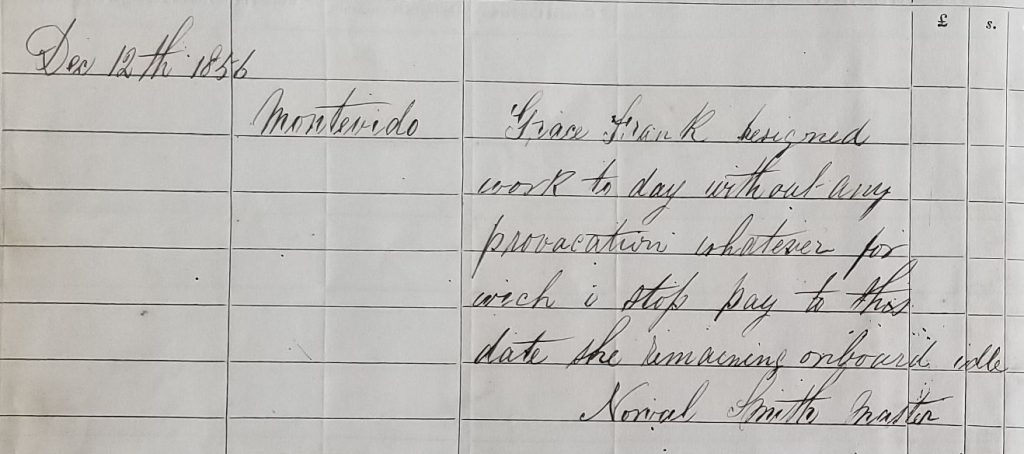

To tell this story, I use a wide range of sources. I have been able to find stories of average women working at sea through collections of Crew Agreements and Official Logbooks, the majority of which are located in the Maritime History Archives at Memorial University of Newfoundland. These collections represent a trove of information on the average seafarer including many women. With the help of digital projects like the Atlantic Canada Shipping Project Database and the CLIP archive, I have been able to trace the careers of several women working at sea in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In a way, these women working at sea were exceptional. Some traveled without their husbands, earned professional wages, or ventured far from home. But their presence in the masculine world of seafaring was not unusual. They demonstrate how the exceptional – that which belies expectations premised on what ‘should be’ rather than what ‘is’ – often was, for many, the everyday. It is these everyday women at sea that are the subject of my research and which prompt a reevaluation of maritime worlds.

[1] “Shipwreck, Attended with Horrid Circumstances,” Morning Chronicle (London, England), March 20, 1826, Issue 17633. British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Violet Jessop, Titanic Survivor: the Newly Discovered Memoirs of Violet Jessop Who Survived Both the Titanic and Britannic Disasters, edited by John Maxtone-Graham (Dobbs Ferry, NY: Sheridan House, 1997), 52.

[5] Ibid., 53.

[6] Ibid., 128.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Jo Stanley, “And After the Cross-Dressed Cabin Boys and Whaling Wives?: Possible Futures for Wome’s Maritime Historiography,” Journal of Transport History 23:1 (2002): 11.

Julia Stryker is a PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, studying women working at sea in the British Empire. Her interests include gender, labor, seapower, and empire, as well migration and maritime law, which she is pursuing as a member of the COST Action Women on the Move. More on her teaching and research interests may be found here: https://jconnellstryker.squarespace.com