By John Gleb

Commentators and scholars have long represented the United States as the supreme guarantor of a well-tempered international order. Today, however, agents of American international relations find themselves confronting uncertainty both at home and abroad. Nevertheless, as they navigate the uncharted waters of contemporary global politics, representatives of the United States and its international interlocutors can still look to their shared past for insight. There are lessons, some positive, some deeply negative, to be learned in the long, complex, and decidedly messy history of the United States in the world.

Produced in collaboration with the Clements Center for National Security, Not Even Past‘s “Uncharted Waters” series is bringing that history to life in detailed case studies, highlighting moments when Americans have grappled with the uncertainties of power. Our aim is to document unease and confusion, hidden dangers and unexpected opportunities. In so doing, we will provide readers with a fresh and provocative perspective on the history of American foreign relations.

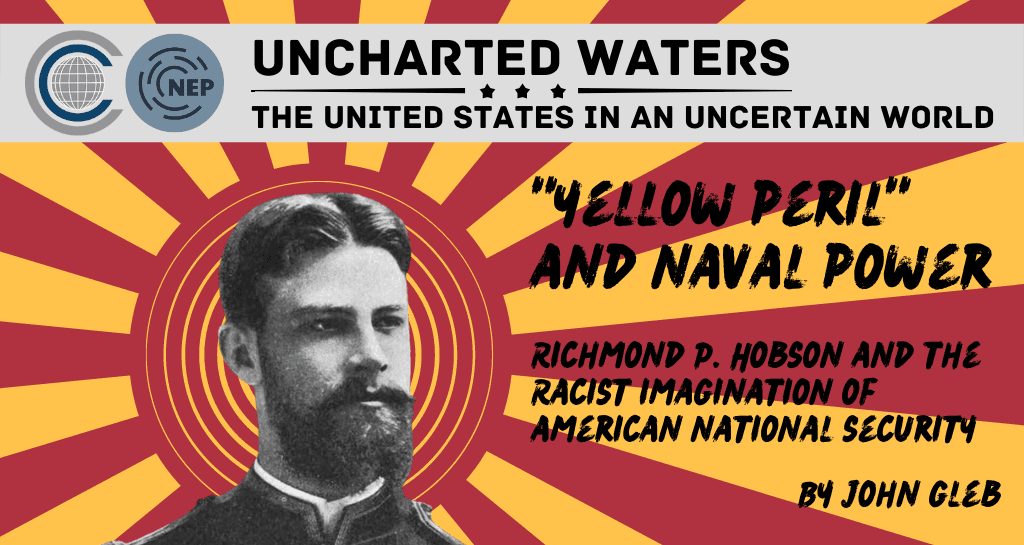

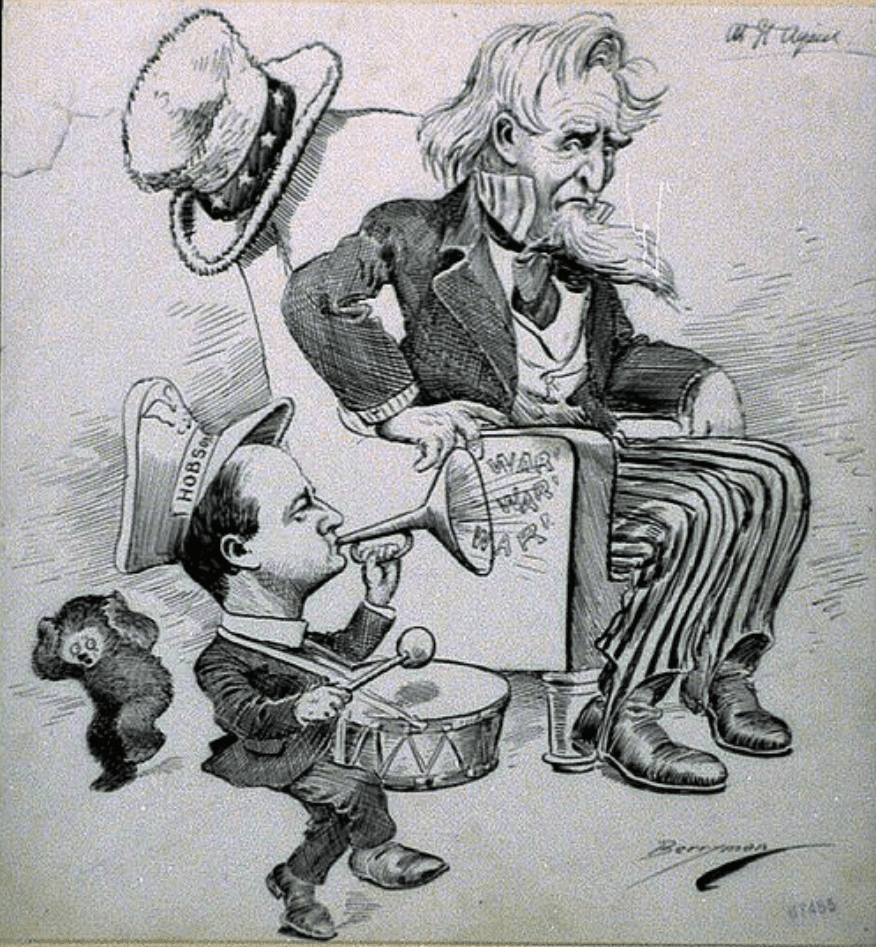

Among the many threats to American national security that experts perceived in February 1909, one in particular stood out to Democratic congressman Richmond P. Hobson of Alabama. Hobson, a former naval officer and celebrated Spanish-American War veteran, maintained an unusually high public profile for a member of the House of Representatives; his reputation as a war hero had allowed him to become a kind of celebrity commentator on world affairs. Now, midway through a long floor speech, he invited his congressional colleagues to consider what he called “the problem of all the ages, the problem that now challenges the good and thoughtful men throughout the world.” The problem had a name: “race antagonism.”[1]

By this, Hobson did not mean what we would call racism—in fact, the Alabama Democrat was himself an unapologetic racist, fully convinced that his own oft-repeated generalizations about white, Black, and “yellow” people were grounded in scientific truths. What alarmed him was the prospect of political instability arising from the tension between geographically adjacent but supposedly incompatible racial communities. Hobson thought he had seen this kind of tension building up for years, and in his opinion, it was growing especially acute in the Pacific. There, he believed, “race antagonism” between “Europeans” and “Asiatics” was threatening to hurl an unprepared United States into a war against Japan.[2]

It goes without saying that this conviction was little more than a racist delusion. Antagonism between Japan and the United States really existed in 1909, but it was not “race antagonism,” the supposedly inevitable byproduct of fixed, irreconcilable racial identities. And of course, while bigots like Hobson may have relied on race to explain human behavior on a grand scale, race itself does not actually determine how people behave.

Nevertheless, the distorted imaginings of Hobson’s racist mind demand careful scrutiny. Not only did they condition his responses to political events both at home and abroad; in doing so, they also performed important intellectual work, reinforcing and eventually transforming the underpinnings of his outlook on foreign affairs. Ultimately, concepts like “race antagonism” mattered both in spite and because of the way they warped the world around them. Through an examination of Hobson’s career and writings, we can place them at the center of a dark but highly significant chapter in the history of national security.

“A Danger and a Responsibility”

To understand how and why Hobson developed his obsession with “race antagonism” in the Pacific, it is first necessary to examine the broader worldview out of which that obsession emerged. At its heart stood a vision of global rivalry between two modes of social order: militarism, which organized societies for the express purpose of waging wars; and industrialism, which harnessed their productive capacities to provide for the well-being of individual citizens. Initially, Hobson saw militarism embodied most clearly in the autocracies of old Europe. The United States, by contrast, supposedly stood at the vanguard of an emerging industrial civilization. The distinction was moral as much as it was political. In a manner that seems eerily familiar today, Hobson cast industrial development as a force for good, claiming that it would break down entrenched social hierarchies, spur the growth of free enterprise, and spread peace and prosperity the world over. Militarism he characterized as the enemy of progress, oppressive, bloodthirsty, and fundamentally barbaric.[3]

Ultimately, Hobson expected industrialism to displace and supplant militarism world-wide. “Nations of prey will have no part to play in the new order of things,” he predicted; “like beasts of prey they are doomed to extinction.”[4] But for the moment, the “nations of prey” appeared to hold one significant advantage over their rivals: in the course of fighting each other, they had developed immensely powerful armed forces. Hobson thought that the existence of these forces placed the United States in an uncomfortable quandary. To contain militarism and ensure its destruction, Americans would have to develop a countervailing military power rooted in their own industrial society. But how could they do so without succumbing to militarism themselves?

By way of an answer, Hobson proposed that naval power, unlike its land-based counterpart, could be built up without stirring any militaristic impulses. The logic behind this surprising proposition was easy enough to follow: because warships could not project force inland, and because they did not require vast reserves of manpower in order to operate, navies supposedly presented no threat civil liberties at home, nor did they enable wars of conquest abroad. On this basis, Hobson spoke out forcefully in favor of expansive naval armament against the militarist threat. “Naval power,” he claimed, “does not involve military organization in the people, and is the natural, logical, form of power for industrialism[,] for free institutions[,] and for peace nations.”[5]

Hobson’s views were idiosyncratic, but his calls for naval expansion were in harmony with mainstream trends. The early twentieth century was the golden age of “navalism,” a political movement which promoted and celebrated the construction of huge, impressive battlefleets. Many prominent Americans were navalists, including President Theodore Roosevelt and the enormously influential military theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan. However, the navalist movement also faced significant organized opposition from pacifists, anti-imperialists, and fiscal conservatives. As a result, although the American navy grew steadily in size and power over the course of Hobson’s political career, it did not do so fast enough to satisfy his increasingly urgent demands.

Hobson responded to navalism’s critics by trying to undercut their base of public support. In speech after speech, article after article, he urged his countrymen to support the assertion of American naval power abroad. But in doing so, he found himself running up against a potentially fatal weakness he thought was inherent in industrial development. The weakness in question was a byproduct of industrialism’s tolerance of individual liberty. On the whole, this seemed like a good thing—but it also made it harder for industrial societies to recognize or respond collectively to national security threats. For this reason, Hobson felt obliged to package his support for naval expansion as a civic obligation to which every American was liable. “American citizens should not blind themselves to the fact that [the] blessing of individual liberty involves a danger and a responsibility,” he warned. The least anyone could do in exchange for liberty’s “glorious privileges” was “to take a lively, active, effective interest in all questions of good government, including the nation’s foreign policies.”[6]

Exciting this “lively, effective interest” became Hobson’s overriding political objective. With missionary zeal, he went again and again before the public, calling attention to supposed militarist plots that seemed to demand a naval response from the United States. “Race antagonism” he regarded as a byproduct of one of those plots. Its source, he claimed, was Japan.

The “Yellow Peril” as a National Security Threat

Hobson’s interest in Japanese militarism began as an interest in China, one of the focal points of American foreign policy ambitions during the early 1900s. At the time, policymakers in Washington coveted China as a vast potential market for American goods and services. Hobson, who assumed that American-led economic development in Asia would further the cause of industrialism, firmly supported his government’s oft-repeated calls for an “Open Door” to the Chinese market. His greatest fear was that some rival power would slam the door shut and subject China to militaristic influences.

Initially, those influences seemed most likely to come from Europe and especially from Russia. Then came the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), which ended in a decisive Russian defeat and made Japan the preeminent military power in eastern Asia. Hobson shed no tears for the Russians, and found himself in fact deeply impressed by Japan’s meteoric rise. Nevertheless, he shuddered at the prospect of Japanese soft power gaining a foothold on the mainland. “The world has been saved from the domination of China in the interest of [European] absolutism,” he wrote, “but it now faces the possibility of a less visible but deeper and more complete domination of China by Asiatic fanaticism.”[7]

“Asiatic fanaticism” was a concept heavily freighted with racist baggage. Indeed, Hobson explicitly characterized the hypothetical Japanese threat to industrialism as a pan-Asian racial threat, a “yellow peril” that would take deliberate aim at white supremacy world-wide. “[C]reating and using race hatred for her purposes,” he warned, “Japan could, unquestionably, bring about the military organization of China”—and the result would be nothing short of apocalyptic. Superimposing racist tropes onto his preexisting anxieties about militarism, Hobson predicted that, “[s]hould the yellow race rise in arms with its preponderance of numbers, and its astonishing aptitude for modern war, Asia would swamp Europe, and there would follow a titanic war between the eastern and western hemispheres that would drench the world in blood and hurl mankind backward to savagery.” [8]

Hobson’s nightmare was a figment of his racist imagination. But it seemed real enough to him, and he began planning a military response. Specifically, Hobson proposed that the United States use its naval power to interdict Japanese access to China if and when the “yellow peril” began to materialize. Not coincidentally, the plan provided its author with a compelling argument in favor naval expansion. “[W]ith a strong navy,” Hobson argued, “we can without war or friction cause Japan to refrain from organizing the Chinese or disregarding the principle of the Open Door; we could insure [sic.] the commercial and industrial organizing of China for the good of all mankind; if we had a strong navy, we would keep the peace in Europe and Asia alike; we could eventually keep the peace of the world.”[9]

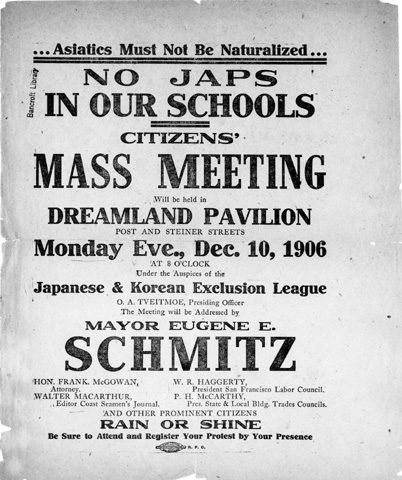

But before Hobson had a chance to put his plan into action, a series of unfortunate events occurred that would transform his preoccupation with the “yellow peril” into a dangerous obsession. The chain of causation began not in China but in San Francisco, California, which had long been a hotbed of anti-Asian racism in the United States. In October 1906, the San Francisco school board attempted to segregate students of Japanese ancestry from their white peers. The school board’s action elicited a formal protest from the Japanese government, unnerving President Roosevelt, who opted to avoid a diplomatic incident by compelling the board to rescind the segregation order. When political leaders from California objected to the federal government’s intervention in what they considered a local affair, the president and his principal advisors warned them privately that allowing the crisis to escalate out of control would risk provoking a military response from Japan. Shocked, one of the Californians promptly leaked the warning to the Washington Post, dramatically escalating a simmering war scare that was starting to alarm officials on both sides of the Pacific.[10]

Even before the scare began, Hobson believed Japan was preparing for a fight. “The Japanese have taken up the cry of Asia for the Asiatics and are now drilling the Chinese in warlike methods,” he had told the Washington Post in August 1906, and by the beginning of 1907, he apparently believed that Japan was “waiting only for a reasonable pretext” to declare war on the United States. Knowing this, on the evening after the Roosevelt administration’s leaked warning appeared in print, a reporter from the New York Times approached Hobson for a comment. The reporter was not disappointed.[11]

“[N]ow I shall say what I really believe,” Hobson announced. Then, smiling and straightening his shoulders, he cut loose: “Japan is spoiling for a fight with this Nation. She is only waiting until she can negotiate loans from Europe. As soon as this has been accomplished you will see that this Government [e. g., the Roosevelt administration] will have to either eat humble pie or fight.” Hobson then turned his attention to the segregation crisis, which he cited as proof of Japan’s malign intentions. His statement to the Times implied that the Japanese protests against anti-Asian racism were deliberately provocative, insofar as they insisted that the federal government desegregate San Francisco’s school system or “suffer the consequences.”[12]

From this point of view, it looked like the president had done the right thing by denying the Japanese the pretext they seemed to be seeking. “Roosevelt was too wise for them,” Hobson told the Times reporter. “He did not want the war he feared would come.” But Hobson also made it clear that appeasement was not an adequate long-term policy. The real solution to the Japanese problem, he suggested, was to achieve control of the Pacific Ocean by accelerating the expansion of American naval power. “Meantime, we must be prepared to eat crow,” he concluded bleakly, “for if a war were to come to-day, we could not send a fleet into the Pacific that could cope with [the Japanese] navy.”[13]

“The Only Way to Get Exclusion”: The Domestic Political Significance of Naval Power

The school segregation crisis powerfully reinforced Hobson’s racially-inflected enthusiasm for naval armament. More importantly, though, it also forced him to reconsider the relationship between world power and domestic politics. Race shaped the way he thought about both, and his obsessive fear of Japan forced them together in his mind.

Hobson recognized that the San Francisco school board’s hostility to students of Japanese ancestry was grounded in the domestic politics of immigration policy on the West Coast, where anti-Asian xenophobes were clamoring for Japanese exclusion. Hobson had not always been a supporter of exclusion legislation. In fact, in the wake of the Russo-Japanese War, he had supported loosening restrictions on Chinese immigration in order to help facilitate the spread of industrialism across the Pacific. But in light of his growing preoccupation with “race antagonism,” Hobson eventually reversed his position. “Wherever two races so far different as to be different in color have come together, one has been subservient to the other, or else endless war has followed,” he wrote in 1908. “The instinct of self-preservation, to escape the fatal consequences of miscegenation, has always engendered race hatred . . . . Following this instinct,” Hobson concluded with approval, “America has excluded Chinese and is now preparing to exclude Japanese.”[14]

It was at this point that the supposed threat of Japanese militarism reentered the picture. For by turning racial injustice into a foreign policy issue, Japan had made it impossible for the United States to enact discriminatory laws without provoking a world crisis. To Hobson, this seemed to leave both countries teetering on the brink of an abyss which only American naval supremacy could bridge. “[T]he possession of a powerful navy is the only way to prevent war following upon the heels of exclusion,” he noted fretfully in a draft of one of his many articles on international affairs. Tellingly, an earlier version of this sentence had ended by asserting that “the possession of a powerful navy is the only way to get exclusion.”[15]

This was an extraordinary claim in and of itself. But its broader implications were equally profound. Naval power, Hobson had come to believe, was more than just an instrument of foreign policy. As one of the bulwarks of national sovereignty, it also played a vital enabling role in the domestic political process. In its absence, Americans would be unable to regulate their internal affairs as they saw fit. This was the lesson Hobson ultimately drew from the school segregation crisis. Alluding obliquely to the tension between industrialism from militarism, he characterized the United States as “a Western democratic republic, built largely upon the right and principal of local self-government,” which had been challenged in the exercise of this right by Japan’s “oriental, absolute monarchy.” Hence the segregation crisis, in which Japanese absolutism had challenged the federal government’s foundational commitment to state and local rights. “Clearly, submission on the part of America can not go on indefinitely,” Hobson concluded. “The challenge of Japan places us in the very presence of war.”[16]

Hobson’s views on school segregation cannot be separated from his identity as a white Democrat from the Deep South. Characteristically, in championing the political rights of racist bigots, he completely ignored the human rights those bigots wanted to violate. Therein lay an enormous contradiction Hobson completely failed to grasp; as a discrete political issue, racism simply doesn’t seem to have mattered to him. What did matter, however, were the twin dangers of “race antagonism” and Japanese military power. Insofar as Hobson could now present those dangers as threats to both national interests abroad and domestic political freedoms, he had found a powerful new means by which to popularize naval expansion.

The Globalization of the American Mind

During the school segregation crisis of 1906–07, local and global politics had collided in a spectacular and illustrative way. Hobson recognized this, and in subsequent years, he exploited it to his advantage. Claims about alleged Japanese assaults on local self-government began to turn up in his speeches and articles. The claims were usually didactic, designed to engage and educate skeptical or distracted audiences. Hobson wanted to prove to the uninitiated that the Japanese threat was real, imminent, and palpably manifest in the lives of American communities.

An especially striking example of this technique marked the climax of the long speech Hobson delivered to Congress in February 1909. The speech’s nominal subject was a bill appropriating money for the diplomatic service. But unsurprisingly, the House soon found itself listening to a lecture on Hobson’s favorite subject, Japanese-American relations. For over fifty minutes, Hobson walked his colleagues through the various points of friction between the two countries. Inevitably, “race antagonism” reared its ugly head; so, too, did the school segregation crisis. Then, Hobson invited the House to consider what he characterized as a second violation of San Francisco’s civic autonomy. The previous year, a Japanese consul had persuaded the municipal government to give five Japanese citizens special permission to sell alcohol locally, despite the fact that a xenophobic city ordinance forbade officials from issuing liquor licenses to foreigners. Hobson made note of the incident for the House’s benefit, claiming—absurdly and erroneously—that the American ambassador to Japan had personally endorsed the Japanese consul’s legally dubious request in order to avoid a diplomatic rupture.[17]

At this point, Hobson prepared to move on to a new topic. But before he could do so, his remarks about the licensing incident caused an uproar on the House floor. Several members of Congress, who were apparently unfamiliar with the local politics of San Francisco, reacted as though their colleague from Alabama had just exposed a major domestic political scandal, interrupting his speech one by one to demand clarification. This annoyed Hobson tremendously, and when a stubborn California congressman tried to pick a fight with him, he lost his temper. “Oh, I am not here to quibble,” he snapped. “The gentleman misses the point entirely.”[18]

Boldly reasserting control of the House, Hobson proceeded to make the point his colleagues had missed. The result was a moment of rhetorical drama that transformed an argument about local politics into a teachable moment on the subject of American national security. The details of the licensing incident receded into the background as Hobson clarified the stakes: at issue, he explained, was not San Francisco’s liquor law but the “inalienable right” of “local self-government”—“the right,” Hobson thundered, “for which Anglo-Saxons have fought for thousands of years [applause], the right for which our forefathers fought.” It was also the right Hobson thought American officials were surrendering under Japanese pressure. But his aim was not to criticize their actions; “On the contrary,” Hobson clarified, “I say it is right for them to do as they have done and are doing, in dropping the Japanese question in legislatures and in city councils. My investigations have shown that there is no way to settle these questions while we are defenseless in the Pacific.”[19]

From here, a pivot back to Hobson’s main theme was easy, and in one fell swoop, the congressman from Alabama laid bare the inner workings of his worldview. “If our people are going to be so neglectful,” he roared, “so self-centered in their own interests, that they will not take an account of their country’s growing danger; will not even open their eyes when daily occurrences show the crying necessity to provide for the power that is needed to have a rational and peaceful settlement of grave difficulties, then it is right for them to put on sackcloth and ashes and submit to the humiliation that is necessary to avoid war.”[20] It was a stinging indictment, and of course, its underlying message was obvious. According to Hobson, so long as the enemies of navalism kept the United States vulnerable abroad, American rights and American honor would remain insecure at home.

The Imagination of National Security

“[I]n the era of globalization in the early twentieth century,” the historian Hajimu Masuda wrote over a decade ago, “global events quickly reached the other side of the earth and influenced local people’s way of thinking, which in turn swayed local politics and, by extension, influenced national and international politics.” Masuda was describing what happened on both sides of the Pacific during and after school segregation crisis. Facilitated by the advent of mass media and high-speed telegraphic communication systems, “considerable antagonism arose. Racism flared up. Newspapers and magazines carried rumors of war. And novels began to imagine possible wars between Japan and the United States.”[21]

Surveying this volatile landscape a hundred years earlier, Hobson had seen evidence of “race antagonism,” a supposedly inexorable, biological force. Masuda saw something different. Instead of blaming the breakdown in Japanese-American relations on deep-seated animus, he cited it as an example of social construction, a process which had allowed spontaneous, uncoordinated expressions of public opinion to change the course of international relations. Persistent popular rumors of war had intersected with localized racial anxieties to generate new rumors in a kind of vicious cycle.[22]

Hobson himself had played an important role in this process. From his bully pulpit in Congress, he insisted that war with Japan was imminent over and over again. His views were controversial, mocked as often as they were praised. But without question, they helped popularize the notion that Japan and the United States were mortal enemies doomed to engage in a fight for control of the Pacific.

Equally significant, however, was the way in which Hobson demonized Japan. His speeches and articles did more than just exaggerate and sensationalize the abstract threat of war. They invited Americans to reimagine the world around them, to see a terrible alien evil lurking behind “daily occurrences” in American domestic politics. For Hobson, globalization was more than just a process facilitated passively by technological change. It was a deliberate act of interpretation, a state of mind.

Hobson clearly anticipated the emergence of what foreign affairs scholar Dexter Fergie has dubbed the “national security imagination,” a way of looking at the world that made an assertive, militarized defense of American democracy “thinkable” during the crisis years of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s.[23] Tragically, one of the forces responsible for catalyzing Hobson’s own national security imagination, and the primary tool with which he sought to awaken it in others, was racism. That’s something we’d do well to remember today. As we turn, once again, to confront a geopolitical rival in the Pacific against a backdrop of rising anti-Asian violence at home, the story of Hobson’s hateful career ought to stand as a powerful warning to all of us. Its protagonist was a demagogue who used racism to hammer home an inflammatory message of inevitable conflict. We should be wary of anyone else who attempts to do the same.

John Gleb is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin and a graduate student fellow at the Clements Center for National Security. John’s research traces the emergence of national security as a concept by documenting attempts to mobilize public opinion on behalf of foreign and defense policy during the early twentieth century.

[1] Congressional Record 43 (1909), 2659.

[2] ibid.

[3] Remarks about militarism and industrialism show up in many of Hobson’s speeches and articles, but for a comprehensive overview, see the undated manuscript entitled “America’s Mighty Mission,” in Box 28, Folder 3 of the Richmond P. Hobson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (henceforth: Hobson Papers).

[4] ibid., 16–17.

[5] ibid., 40–42.

[6] ibid., esp. 20–22.

[7] Hobson laid out his views on China, Russia, and Japan in an unpublished manuscript entitled “American Naval Policy in Light of the Russo-Japanese War” (Hobson Papers, Box 28, Folder 3). Part of the manuscript appears to be missing, but what survives conveys a great deal of substance, and a long section on Japan remains intact. Hobson did not date the manuscript, but since its analysis of the Japanese threat makes no mention the San Francisco school segregation crisis (described later in this essay), it seems safe to assume that he wrote it before 1907.

[8] ibid.,47–48.

[9] ibid., 56–59.

[10] For a detailed account of the school segregation crisis and its international ramifications, see Charles E. Neu, An Uncertain Friendship: Theodore Roosevelt and Japan, 1906–1909 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014 [orig. 1967]), esp. 20–88. A more recent article on the war scare itself is Masuda Hajimu, “Rumors of War: Immigration Disputes and the Social Construction of American-Japanese Relations, 1905–1913,” in Diplomatic History 33/1 (2009): 1–37. For the leak, see “Seek to Avert War: President, Root, and Taft Point Out Crisis over Japan,” Washington Post, 1 February 1907, 1.

[11] “Perkins Expects a Conflict,” New York Times, 2 February 1907, 2. For Hobson’s August 1906 comment, see “Captain Hobson Sees Peace in Great Navy,” Washington Post, 8 August 1906, 4.

[12] “Perkins Expects a Conflict,” 2.

[13] ibid.

[14] For these remarks, see pp. 35–36 of the unpublished draft of Hobson’s article “Disarmament,” dated September 1908, in the Hobson Papers, Box 28, Folder 2. Part of this draft was published the following month under the same title in the American Journal of International Law 2/4 (1908), 743–57. However, the published version omits the draft’s lengthy discussion of exclusion and the Japanese military threat in the Pacific.

Hobson criticized Chinese exclusion in his manuscript on “American Naval Policy in Light of the Russo-Japanese War.” He did so, however, on explicitly racist grounds: assuming that hard work was naturally “congenial to the Chinese,” he argued that white Americans should let “the chinaman” free them from any obligation to perform “cramping and injurious forms of labor.” “In the great industrial life of the world now opening up,” he wrote, “there will be chinamen enough to keep all the white men engaged in supervision, directing, controlling, and organizing, forms of work adapted to the white man.” Hobson, “American Naval Policy” manuscript, 44.

[15] Hobson, “Disarmament” draft, 36.

[16] ibid., 37–38.

[17] For the full text of Hobson’s speech, see Congressional Record 43 (1909), 2655–62. Hobson’s remarks on “race antagonism,” the school segregation crisis, and the liquor licensing incident all appear on p. 2659.

[18] ibid., 2659–60.

[19] ibid., 2660.

[20] ibid.

[21] Masuda, “Rumors of War,” 4.

[22] This is the main argument presented in ibid.

[23] On the “national security imagination,” see Dexter Fergie, “Geopolitics Turned Inward: The Princeton Military Studies Group and the National Security Imagination,” Diplomatic History 43/4 (2019): 644–70.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.