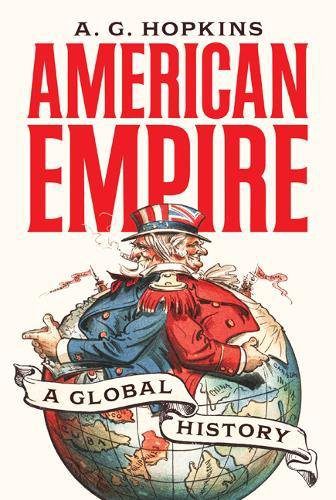

Whether commentators assert that the United States is resurgent or in decline, it is evident that the dominant mood today is one of considerable uncertainty about the standing and role of the “indispensable nation” in the world. The triumphalism of the 1990s has long faded; geopolitical strategy, lacking coherence and purpose, is in a state of flux. Not Even Past, or perhaps Not Ever Past, because the continuously unfolding present prompts a re-examination of approaches to history that fail to respond to the needs of the moment, as inevitably they all do.

This as good a moment as any to consider how we got “from there to here” by stepping back from the present and taking a long view of the evolution of U.S. international relations. The first reaction to this prospect might be to say that it has already been done – many times. Fortunately (or not), the evidence suggests otherwise. The subject has been studied in an episodic fashion that has been largely devoid of continuity between 1783 and 1914, and becomes systematic and substantial only after 1941.

This as good a moment as any to consider how we got “from there to here” by stepping back from the present and taking a long view of the evolution of U.S. international relations. The first reaction to this prospect might be to say that it has already been done – many times. Fortunately (or not), the evidence suggests otherwise. The subject has been studied in an episodic fashion that has been largely devoid of continuity between 1783 and 1914, and becomes systematic and substantial only after 1941.

There are several ways of approaching this task. The one I have chosen places the United States in an evolving Western imperial system from the time of colonial rule to the present. To set this purpose in motion, I have identified three phases of globalisation and given empires a starring role in the process. The argument holds that the transition from one phase to another generated the three crises that form the turning points the book identifies. Each crisis was driven by a dialectic, whereby successful expansion generated forces that overthrew or transformed one phase and created its successor.

The first phase, proto-globalisation, was one of mercantilist expansion propelled by Europe’s leading military-fiscal states. Colonising the New World stretched the resources of the colonial powers, produced a European-wide fiscal crisis at the close of the eighteenth century, and gave colonists in the British, French, and Spanish empires the ability, and eventually the desire, to claim independence. At this point, studies of colonial history give way to specialists on the new republic, who focus mainly on internal considerations of state-building and the ensuing struggle for liberty and democracy. Historians of empire look at the transition from colonial rule rather differently by focussing on the distinction between formal and effective independence. The U.S. became formally independent in 1783, but remained exposed to Britain’s informal political, economic and cultural influences. The competition between different visions of an independent polity that followed mirrored the debate between conservatives and reformers in Europe after 1789, and ended, as it did in much of Europe, in civil war.

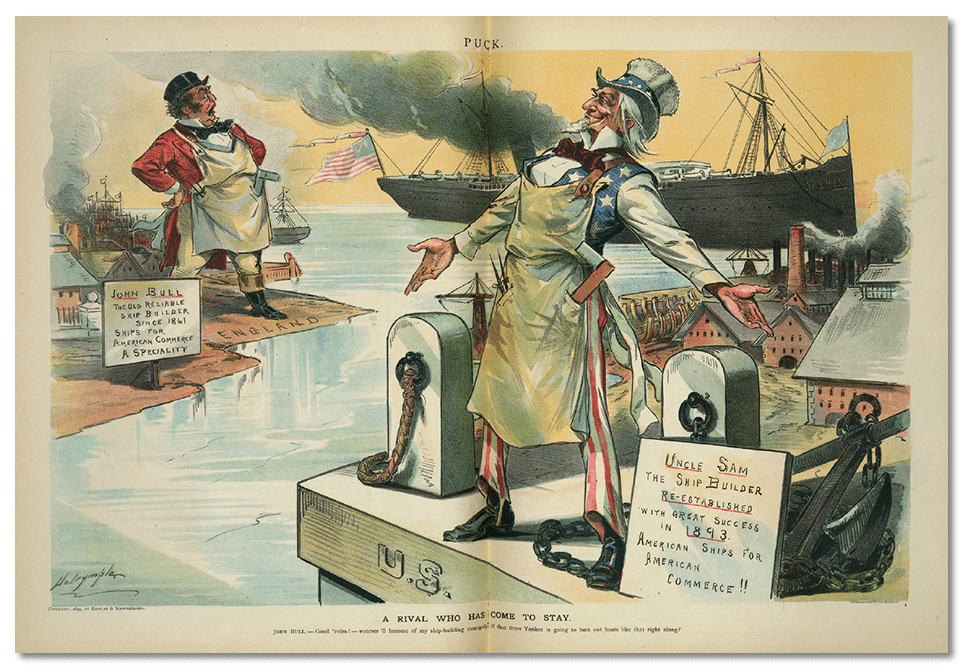

“A Rival Who Has Come to Stay. John Bull – Good ‘evins! – wotever ‘ll become of my ship-building monopoly, if that there Yankee is going to turn out boats like that right along?” Puck magazine, July 24, 1895 (via Library of Congress)

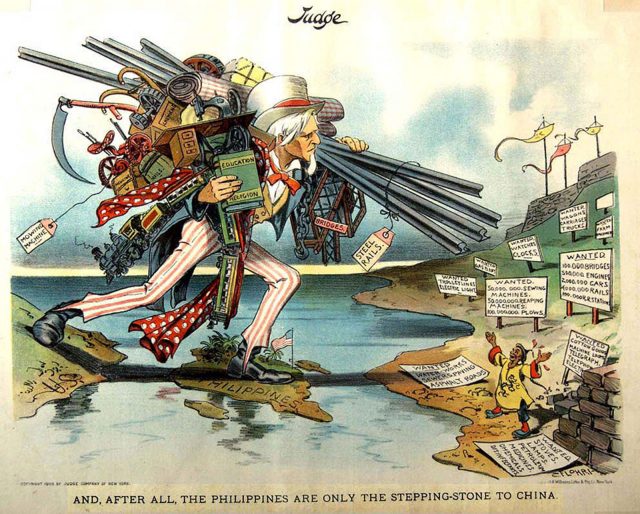

The second phase, modern globalisation, which began around the mid-nineteenth century, was characterised by nation-building and industrialisation. Agrarian elites lost their authority; power shifted to urban centres; dynasties wavered or crumbled. The United States entered this phase after the Civil War at the same time as new and renovated states in Europe did. The renewed state developed industries, towns, and an urban labor force, and experienced the same stresses of unemployment, social instability, and militant protest in the 1880s and 1890s as Britain, France, Germany and other developing industrial nation-states. At the close of the century, too, the U.S. joined other European states in contributing to imperialism, which can be seen as the compulsory globalisation of the world. The war with Spain in 1898 not only delivered a ready-made insular empire, but also marked the achievement of effective independence. By 1900, Britain’s influence had receded. The United States could now pull the lion’s tail; its manufactures swamped the British market; its culture had shed its long-standing deference. After 1898, too, Washington picked up the white man’s burden and entered on a period of colonial rule that is one of the most neglected features of the study of U.S. history.

Columbia’s Easter Bonnet: In the wake of gainful victory in the Spanish–American War, Columbia—the National personification of the U.S.—preens herself with an Easter bonnet in the form of a warship bearing the words “World Power” and the word “Expansion” on the smoke coming out of its stack on a 1901 edition of Puck (via Library of Congress)

The third phase, post-colonial globalisation, manifested itself after World War II in the process of decolonisation. The world economy departed from the classical colonial model; advocacy of human rights eroded the moral basis of colonial rule; international organisations provided a platform for colonial nationalism. The United States decolonised its insular empire between 1946 and 1959 at the same time as the European powers brought their own empires to a close. Thereafter, the U.S. struggled to manage a world that rejected techniques of dominance that had become either unworkable or inapplicable. The status of the United States was not that of an empire, unless the term is applied with excessive generality, but that of an aspiring hegemon. Yet, Captain America continues to defend ‘freedom’ as if the techniques of the imperial era remained appropriate to conditions pertaining in the twenty-first century.

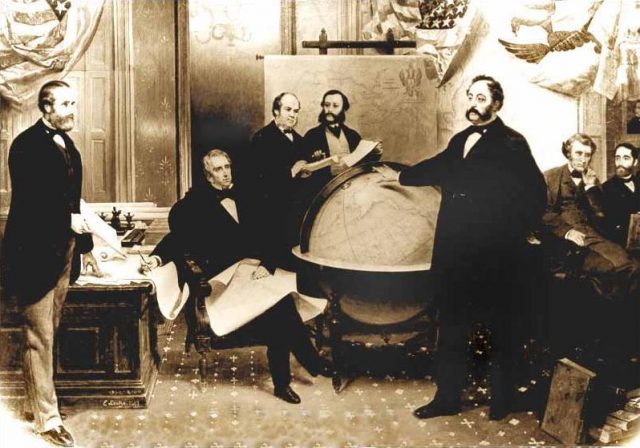

The signing of the NATO Treaty, 1949 (via Wikimedia Commons)

This interpretation inverts the idea of “exceptionalism” by showing that the U.S. was fully part of the great international developments of the last three centuries. At the same time, it identifies examples of distinctiveness that have been neglected: the U.S. was the first major decolonising state to make independence effective; the only colonial power to acquire most of its territorial empire from another imperial state; the only one to face a significant problem of internal decolonisation after 1945. The discussion of colonial rule between 1898 and 1959 puts a discarded subject on the agenda of research; the claim that the U.S. was not an empire after that point departs from conventional wisdom.

The book is aimed at U.S. historians who are unfamiliar with the history of Western empires, at historians of European empires who abandon the study the U.S. between 1783 and 1941, and at policy-makers who appeal to the ‘lessons of history’ to shape the strategy of the future.

A.G. Hopkins, American Empire: A Global History