By Isaac McQuistion

A story published on Quartz.com shortly after the election proclaimed that history classes are our best hope for teaching people to question fake news and beat back the narrative of “Make America Great Again” and the white nationalism inherent in it. The study of history encourages the use of critical thinking and the questioning of received narratives, to ask why certain things are the way they are.

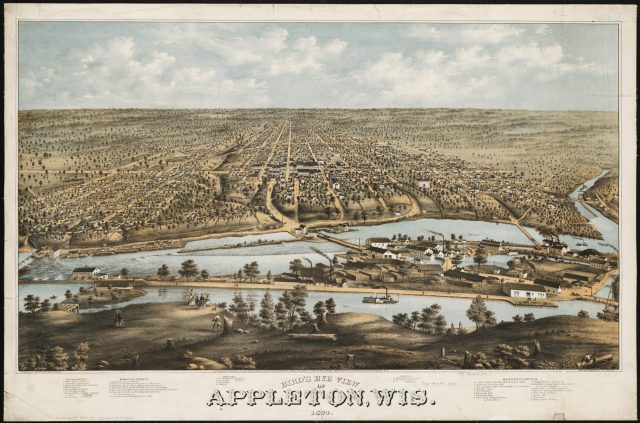

A historical blind spot of mine for a long time was my local community. It might stem from the teachers I had or the narrative we were given, but I could never find much to get excited about when the subject was state or local history. I grew up in Wisconsin, a state best known for cheese, the Packers, and dull monotony. I looked around my hometown and all I heard were stories about the paper mills and the occasional French fur trader. Everything looked the same, including the people. Especially the people.

My hometown is overwhelmingly white. That includes me. According to the 2010 census, only 1.7% of people in Appleton, a city of about 75,000, reported themselves as African-American. That translates to about 1,200 people. The entire time I lived there, I had never bothered to ask why there were so few African-Americans in Appleton. I simply accepted it as the way of things.

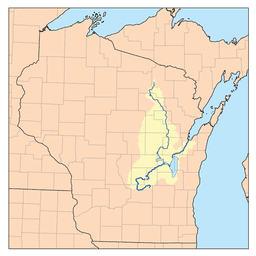

It was my father who forced me to think about the historical roots of why this was. He’s a pastor in Appleton, and he’s probably the person most responsible for giving me my love of history. While talking with him recently, he mentioned that he went to something called a “plunge,” an event organized by a local organization that aimed to get community leaders together and have them explore, in-depth, a particular issue. The topic for this plunge was “being black in the Fox Cities” (the loose conglomeration of towns that sprung up around the Fox River, and of which Appleton is the largest).

Prior to this, my father admits that he hadn’t given much thought to Appleton’s African-American population. For one, the population is incredibly small. For another, Appleton seems to exude a kind of neighborly warmth, that stereotypical feeling of simple Midwestern friendliness that lulls some into idolizing the area. To most appearances, Appleton does not have a problem with race relations, not in the same way that other cities, like Milwaukee, do.

This, my father quickly realized, was a lie. Several minority students from the local college shared their experiences living in Appleton. They told about how they’d been tailed in stores and stopped multiple times by the police on the flimsiest of pretenses. How they felt like they were constantly being surveilled. How most days when they’ve been walking down College Avenue, the main thoroughfare in the city, they’ll have a racial slur hurled at them.

The low number of African-Americans in the city also isn’t incidental. As part of the event my father attended, a curator from the local history museum gave a presentation on the black experience in Appleton. He described widespread institutional racism that decimated African-American population in the area.

Up until the 1920s, the black population in Northeast Wisconsin was small but stable. Precise numbers are hard to come by, since census workers didn’t bother to take account of many of the working poor in the towns and cities. It was by no means an idyllic time or one free of racism, but it also wasn’t unusual to see black-owned businesses and a few African-Americans were even elected to public office.

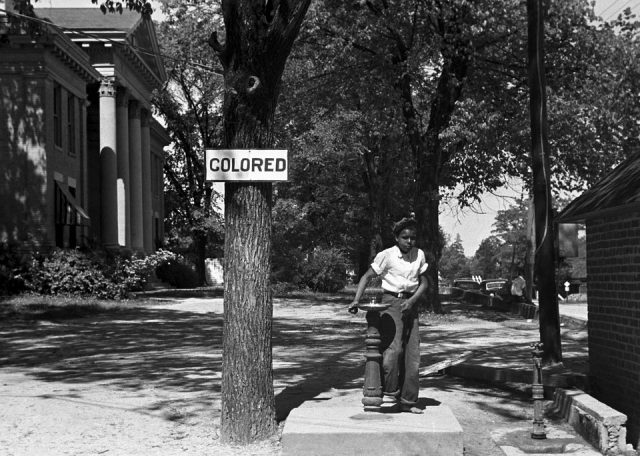

Following World War I, however, growing racism forced much of the black population in the Fox Cities to leave for larger black communities in urban areas. An anti-vagrancy ordinance allowed police to freely discriminate against the black population, as well as others who were thought of as “undesirable foreign elements.” Though some black people could buy homes after the Civil War, in the 1920s subdivisions began specifically excluding blacks.

“Sundown Towns,” that breed of municipality that dictated that all black people leave the city by sunset, sprang up around the country. Appleton had no official ordinance designating it as such, but many supported the custom, to the point where it became one by default.

At the same time, membership in the resurgent Ku Klux Klan grew. A photo of a 1925 Klan rally from the Oshkosh Public Museum shows a crowd of thousands gathered together not under cover of night, but in the middle of the day, packed into a baseball stadium. Churches specifically encouraged Klan members to attend their services and openly recruited from the pulpit.

The net effect of all of these different forms of discrimination was that, according to the 1930 census, the black population in Appleton had plummeted to zero.

For years, discriminatory practices continued in many establishments, despite the passage of anti-discrimination laws. Black athletes and performers would often avoid the city outright. Alabama Governor George Wallace found the environs friendly enough to launch his 1964 presidential campaign at the Appleton Rotary Club, using his speech to decry what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1963 as “The Involuntary Servitude Act of 1963.”

It’s only been in the past few decades that Appleton’s African-American population has begun to recover. As late as 1980 it stood at only 31 people. Now, it’s about even with what was seen in the years after the Civil War. It wouldn’t be until the 2000s that African-American politicians would again hold local office.

My father, previously unaware of this history and ignorant of the racism prevalent in his community, found himself in a position to do something. He met with another pastor in the city who led a majority African-American congregation. They decided to have their churches team up to volunteer around town, worship together, and attend each other’s fellowship gatherings. They’ve worked with a local Christian youth camping organization to provide day camp and summer camp opportunities for local kids. The idea, more than anything, is to start a dialogue, to have the two congregations get to know each other and to see a little bit of the world through the others’ eyes.

These are small steps, to be sure, but they are a start. My father often talks of growing up in rural Ohio and hearing those around him espouse racist views and use racial slurs. He counts himself as a conservative and has lived most of his life in majority-white areas. He mentions that he took every course on African-American history that was offered at his college to try and free himself from the patterns of thought that characterized his upbringing and surroundings. But there’s an immediacy that comes with knowing the history of the place you live. This knowledge has opened his eyes to an experience completely different from his own, to the way racism has shaped his town and what he can do to help. This, a historical knowledge of our local communities, is what can drive change. And if there ever was a time when we needed to think historically about our local communities and our nation as a whole, it’s now.

History isn’t some abstract thing. It doesn’t just happen at a national or global level, and its effects aren’t remote to us. History is what shapes our daily lives. Once we realize that, once we start thinking historically about where we are, we can see that nothing just happens. Things are not just as they are; they are always as we’ve made them to be. A fuller reckoning of our past helps us determine what we want to build for the future. This, then, is what thinking historically ultimately does for us: it helps us see that what we do today will one day become history.

All information about Appleton’s black population is drawn from A Stone of Hope: Black Experiences in the Fox Cities, an exhibit put together by The History Museum, owned and operated by the Outagamie County Historical Society.

![]()

You may also like:

Jacqueline Jones expounds on the Myth of Race in America.

Emily Whalen reviews a book that discusses how American cities are tied to American politics.

Caroline Murray examines the history of indigenous Los Angeles through a public mapping project.

![]()