By Jacob Doss

What do virility, erotic passion, and child abandonment have to do with the history of Christianity? In her collection of essays entitled From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature, Barbara Newman addresses these subjects in relation to a shift in gender ideologies in the medieval Church between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. Newman’s essays explore ways women expressed holiness within an oppressive medieval religious culture. Newman is particularly interested in a gradual shift in gendered models of behavior from, what she terms the virago, or virile woman, to the “womanChrist.”. According to the virago model, women were measured against a normative male expression of righteousness. They could be equal to men inasmuch as they became like men. Women’s holiness entailed conquering their innate weakness and becoming virile. Conversely, the womanChrist model represented an emerging ideology of gender complementarity. According to this budding, though not universally accepted model, women could achieve holiness through devotional practices that drew upon their innate “femininity.”

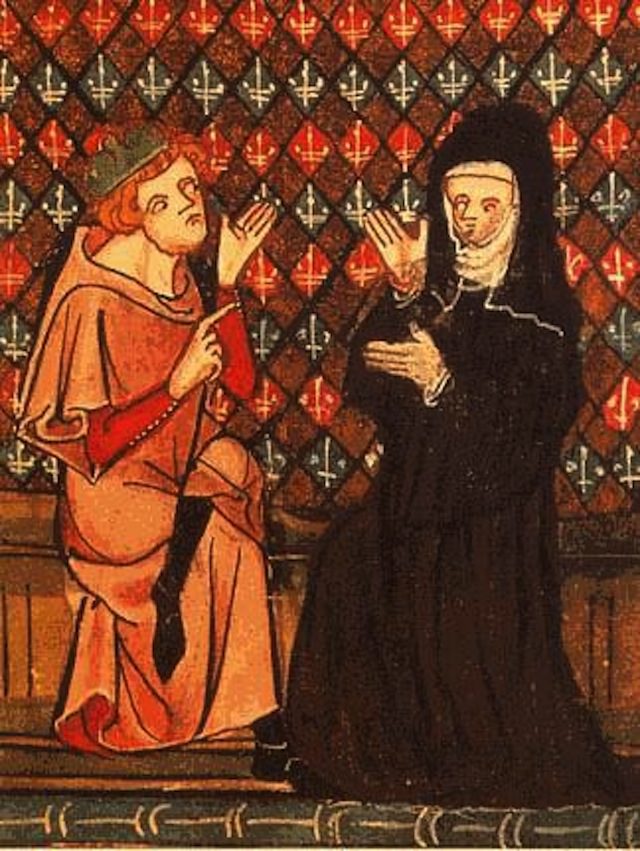

Newman begins in the twelfth century by comparing pastoral writings by men for religious women with those meant strictly for men. Using the letters of Heloise and Abelard as a ground for her analysis, Newman, echoing Heloise, asks a basic, but significant question, “is the nun’s life gendered or gender-neutral?” Abelard responds to Heloise by suggesting the basics of religious life are fit for both sexes, echoing the long-standing virago tradition; however, he then explains the inherent virtue and potential superiority of religious women. For Abelard, God’s power was more evident in holy women than holy men because of women’s inherent weakness. Furthermore, holy women enjoyed a closer relationship to God by virtue of their being “brides of Christ.” Exalted bridal status, however, was contingent on the strict maintenance of virginity. Women were thought particularly prone to lasciviousness, therefore imperiling their exalted but precarious status. In order to protect women (and men) from their lascivious, passionate, and impulsive nature, the church advised strict enclosure for religious women behind the monastery walls.

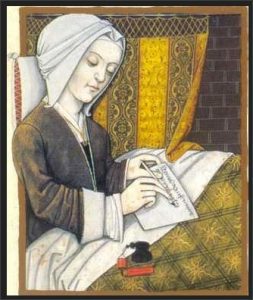

Newman finds the transition from virago to womanChrist in those supposed female shortcomings. Heloise, whose “chief claim to fame was…erotic passion,” did not aspire to spiritual virility, nor was she concerned with maintaining chastity. Through Heloise’s letters to Abelard, Newman finds the geneses of a “feminine” spiritual discourse of desire. Within this understanding a particularly female spirituality grew out of women’s innate passion and their propensity for intense love. This discourse championed passion, loyalty, and absolute self-surrender to the beloved. Newman reads Heloise as a “mystic manquée” whose language and impulses would later re-emerge in the mystical writings of the beguines, an urban, lay religious movement, consisting primarily of women, focused on works of charity and adherence to voluntary poverty.

A particular feature of the womanChrist model is that of vicarious suffering. Drawing on the Passion and the Virgin Mary’s life as models, cultivation of this suffering, along with a loving desire for and fearless obedience to Christ was often the goal of devotional literature for women. Though Heloise’s desire was for Abelard, three famous beguines, Hadewijch, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and Marguerite Porete, used similar language to express their desire for and dedication to Christ. These beguine writers preferred to suffer in Hell if that were God’s will and might vicariously save others from the fire. For some mothers, the suffering that followed abandoning their child or allowing its death came to be praised. By merging the story of Abraham and Isaac with the Virgin Mary’s willing, but excruciating, personal sacrifice of her child on the cross, mothers had an innovative model of suffering to imitate. Children were sacrificed or abandoned to free their mothers to take monastic vows.

Another way women imitated Christ through their femininity was their “apostolate to the dead.” Women, now clearly exhibiting Newman’s womanChrist model, could reduce the deceased’s time in purgatory through their own suffering, thus mirroring Christ’s passion and descent into Hell to rescue the souls held captive there. A late thirteenth-century heterodox sect, the Guglielmites, further illustrate emerging notions of gender complementarity and the redemptive potential of women. They claimed their leader, Guglielma, was the Holy Spirit incarnate. Her promoters preached that the feminine Holy Spirit and a female leadership would restore the wayward Church to its true glory. Newman ends with a work lauding femininity, Cornelius Agrippa’s early sixteenth-century treatise On the Nobility and Superiority of the Female Sex. Newman argues that Agrippa’s work, though potentially satirical, illustrated a time of convergence where both female gender models, the virago and the womanChrist, could be employed as an intellectual challenge to patriarchy.

Newman’s essays illustrate a significant shift from an ancient Christian gender model to a gender complementarity model still prevalent today. Women’s roles in Christianity are still a cause of debate, illustrated by Jimmy Carter’s recent resignation from the Southern Baptist Convention over women’s unequal roles in leadership and the Vatican’s controversial investigation of American nuns. Similarly, in the context of the Vatican’s “Humanum: An International Interreligious Colloquium on The Complementarity of Man and Woman,” Newman’s study remains relevant to understanding current Christian gender ideologies. Newman illuminates Christianity’s longstanding subordination of women and how women undermined patriarchy, while revealing the origins of current models. The stories Newman relates are often shocking, interesting, and counterintuitive. Rather than anachronistically seeing her subjects’ actions as illustrating personal commitments to self-empowerment or conscious subversion, Newman rightfully understands her subjects’ stories to be based in expressions of their religion, thus seeing their self-understanding as products of the texts and traditions of Christianity.

Barbara Newman, From Virile Woman to Woman Christ: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995)

You may also like:

Julia Gossard reviews State of Virginity: Gender, Religion, and Politics in an Early Modern Catholic State by Ulrike Strasser (2004).

Miriam Bodian discusses seventeenth-century radical theology

All images via Wikimedia Commons.