I lived near the port city of Kesennuma, in northeastern Japan, from 2006 to 2008. That was several years before the event they call 3/11. That’s March 11, 2011, the day a record-setting earthquake and tsunami devastated the area and cost over 18,000 lives. Most of the victims were Japanese, but several foreigners died as well, including two Americans who were doing same the job I had done: teaching English in elementary and junior high schools.

I kept in touch with several friends in Japan after I returned to the United States to attend graduate school. When the tsunami hit and it became clear just how bad the damage was, there was a long, tense period as I waited to hear from them through email or Facebook or mutual acquaintances. Fortunately, nobody I knew died in the tragedy. But many of them did lose their homes, their cars, and their own family members, friends, students, and neighbors.

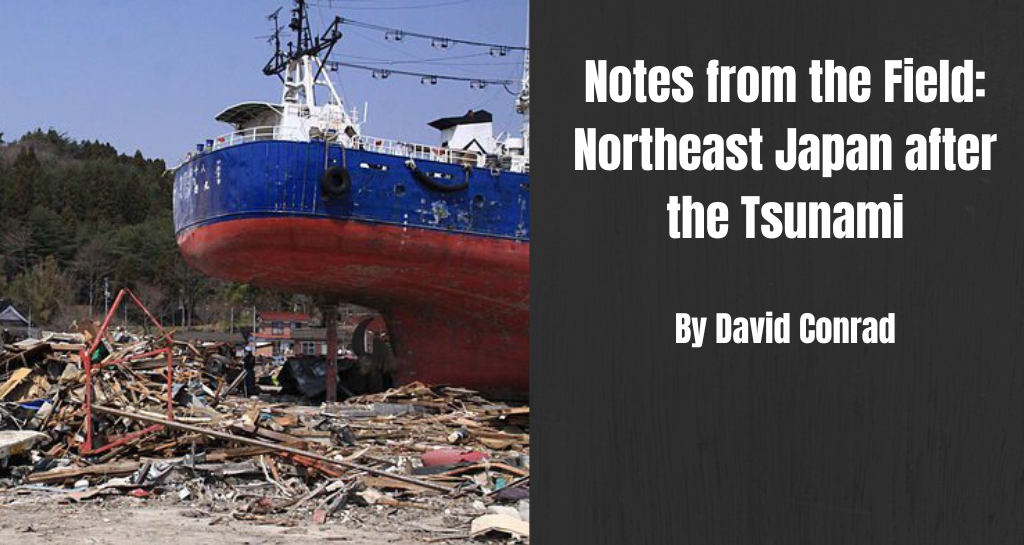

I couldn’t help but wonder how the place I used to live had changed. In the months following the disaster I heard about the shops and homes that had been washed away, about the temporary housing that cropped up, and about the giant beached ships (Kesennuma is a major commercial fishing port) that were left sitting inland after the waters receded.

My dissertation involves Japan, though it is not related to the tsunami, and I received the opportunity to research there for the 2013-2014 academic year. I was thrilled to go back, and even more thrilled that through happenstance and the invaluable help of Japanese historians on both sides of the Pacific I was able to live in the same general part of the country I had lived in years before. This time I was three hours away from Kesennuma, close enough to visit relatively easily.

Nothing I had heard could have prepared me for what I saw there. While many buildings I recognized were still standing, and some had already been rebuilt, large swaths of the town were simply gone. One of Kesennuma’s two rail stations had been destroyed, and I did not have a car, so I traveled there by bus. It dropped off in the middle of several cracked foundations. Only by memory could I tell that I was a stone’s throw from the site of a restaurant I used to frequent. A friend picked me up at the bus stop, and on our way to his home in my old neighborhood we passed a fishing vessel tipped on its side. The ocean was several meters away on the righthand side of the road, and the ship was on the left.

In my old neighborhood we drove past the site of an elementary school I used to teach at. It had been a century-old wooden building, architecturally beautiful but with a permanent stench from bad plumbing. It had probably needed to be replaced, but not like this. In its place was a cluster of small, plasticky temporary houses that stood out among the modern homes and large, old wooden ones that survived the disaster. Many observers have argued, and I agree, that the Japanese government has been too slow to replace the tens of thousands of destroyed residences in the affected parts of the country.

While there was ample physical evidence of the disaster, the attitudes of the people I met and renewed friendships with were almost universally “genki”—a Japanese word meaning healthy, happy, and lively. One friend who lost her home and her business on 3/11 treated me to her memories of that day, and concluded by insisting “This [loss of property] is not sad. Because there were many people who lost their lives.”

However, the nuclear aspect of the disaster is still a source of concern for many. The troubled and leaking Fukushima reactor is just a few hours south of Kesennuma. I visited one shop in nearby Sendai City that advertised “Fukushima-free” foods, made without any agricultural or sea-based products from the area around the plant. Every scientific study I know of has determined that food from most of Fukushima is safe to eat, but farmers there are having a hard time convincing the public to buy their goods. Almost every day’s television news broadcast leads with an update on the damaged plant. On the other hand, at one sushi party I attended another foreigner asked whether any of the fish was from waters off Fukushima. A Japanese patron responded, “Maybe, but we can’t worry about it.” Not to eat fish is too great a sacrifice.

While in Japan I hosted several visitors from America (and two from Australia), and they all reported having a wonderful time. Disaster-affected areas are working to increase tourism to help their ongoing recovery. It is safe to visit the northeast of Japan, and the area is home to several unique, ancient sites that are off the usual tourist path but every bit as rewarding as locations in Tokyo and Kyoto. If you get a chance to go, let me know, and I’ll give you a list. I miss Japan greatly and look forward to going back again someday.