Judith Brown’s Gandhi, Prisoner Of Hope published in 1989 amply reflects the decades of quality research that went into its production. Brown elucidates  Gandhi’s transition from being “a man of his time” to “a man for all times and all places” by his unswerving and whole-hearted submission to the idea of satyagraha or truth-force, most significantly reflected in the deep questions that he asked, many of which he himself did not find answers to. Brown’s biography breaks many a myth about Gandhi and encourages readers to evaluate his life and achievements for themselves, as they find access to Gandhi’s own voice, that of his contemporary’s opinions on him and even the attitudes of the Raj’s officials towards Gandhi.

Gandhi’s transition from being “a man of his time” to “a man for all times and all places” by his unswerving and whole-hearted submission to the idea of satyagraha or truth-force, most significantly reflected in the deep questions that he asked, many of which he himself did not find answers to. Brown’s biography breaks many a myth about Gandhi and encourages readers to evaluate his life and achievements for themselves, as they find access to Gandhi’s own voice, that of his contemporary’s opinions on him and even the attitudes of the Raj’s officials towards Gandhi.

The title renders to the readers two aspects of Gandhi’s life. First, the book describes Gandhi’s career from being a “nonentity” in England to symbolizing Indian identity to the world; from being an unsure leader in South Africa in his early middle age to becoming the central public figure in India in his old age. The book carefully constructs the image of Gandhi, juxtaposing it against the popular image of him as Mahatma, or “Great Soul,” a title by which he began to be called much before any of his ideas were accepted or executed on a large scale. Brown tries to project the man behind the mahatma, with his failings, doubts, mood swings and blood pressure problems. Second, Brown projects the ideological and philosophical mind of Gandhi, tracking carefully the origins of his ideas, be it satyagraha, non-violence, civil-disobedience or his stand against westernization and modernization; their development, their timely execution and their fall out. In this process Brown sets the groundwork on which she is able to explain how time and again, almost ironically, Gandhi falls in his own esteem in trying to execute his ideas, yet tries again, and how in doing so with uncompromising optimism, Gandhi became a “prisoner of hope.”

Brown does not praise Gandhi uncritically nor does she place him on a pedestal, above human beings and closer to the God that Gandhi so relied on. The beauty of her work lies in the way she discovers the mahatma in Gandhi, almost at the end of the book. In the epilogue Brown’s thesis comes to a full circle and she shows how Gandhi’s greatness, his well deserved praise, lay in being a flawed man but being courageous enough to correct those flaws. Gandhi, a frail man by stature, emerges in Brown’s works one of the strongest men in history. “God centered and man oriented,” Gandhi searched for “[H]im in humanity” and there lay his strength.

Photo Credits:

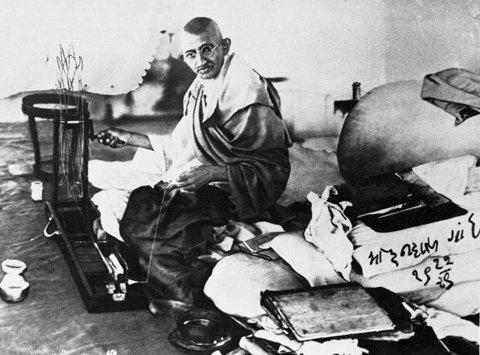

Left: Gandhi spinning, December 1929 (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

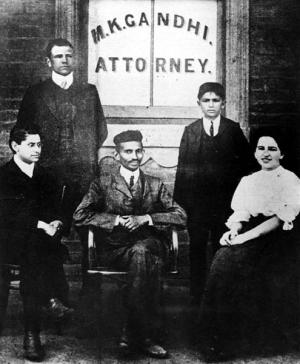

Right: Gandhi at his Johannesburg law firm, 1905 (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)