When Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún arrived in New Spain (Mexico) in 1529, he embarked on an extraordinary project: the compilation of an encyclopedic compendium of the world of the Aztecs in the wake of the Spanish conquest a decade earlier.

Finally completed between 1576 and 1577 – essentially Sahagún’s life’s work – the result was the Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España (the General History of the Things of New Spain). Sometime between 1578 and 1584 the manuscript was taken to Spain and by 1588 Sahagún’s Historia found its way to Florence, part of the Medici family’s magnificent collections. How exactly the Historia came into Medici hands remains unclear but that is where it still resides today, in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, which explains how the Historia became more commonly known as the Florentine Codex.

Sahagún’s motivations for such an ambitious project can be found in his linked objectives to compose works in Náhuatl — the Aztecs’ main language — and to gain an understanding of the religious and cultural beliefs of the indigenous peoples in order to facilitate their meaningful conversion to Catholicism. Sahagún is often described as “the first anthropologist” or “ethnographer” because of the methods he employed in the collection and analysis of the information he gathered. His “ethnographic” practice included collaborations with indigenous elders as cultural informants from central Mexican towns. He also worked closely with Christianized young indigenous students and “grammarians” – indigenous scholars able to read and write in Latin, Spanish, and Náhuatl – and who Sahagún had taught in the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, a school established in 1536 specifically to educate the sons of indigenous elites in grammar, rhetoric, and theology.

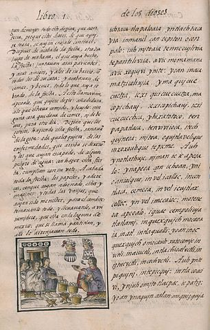

Sahagún framed a series of questions for the indigenous elders on a wide range of topics that included their pre-conquest religion and rituals, natural history, education, and medicine, as well as on the Spanish conquest. The indigenous elders’ responses to Sahagún’s questions were recorded through their “paintings” — a pictographic and ideographic form of writing. The indigenous “grammarians” and scribes, in turn, translated their responses and transcribed them into Náhuatl written in the Latin alphabet. To complete the process, Sahagún provided abbreviated Spanish translations of the Náhuatl responses and indigenous artists or tlacuilo provided illustrations.

This process is embodied in the characteristics and physical appearance of the Florentine Codex. Composed of twelve books, a total of some 2,400 pages of text accompanied by a staggering 2,468 ink and color illustrations, and organized by individual topic (e.g. “Book I. The Gods,” “Book VII. The Sun, Moon, and Stars and the Binding of the Years”), the result is a bilingual codex with its pages divided into two parallel columns of Náhuatl and Spanish text.

Although scholars have long acknowledged the inestimable value of the textual descriptions contained within the Florentine Codex, less attention has been paid to the illustrations in their own right. Fortunately, that is changing thanks to Diana Magaloni Kerpel’s innovative research and her insistence that we need to think about the Florentine Codex “as a work of art.” Her study illuminates the creative processes at work in the Florentine Codex and the indigenous artists behind them.

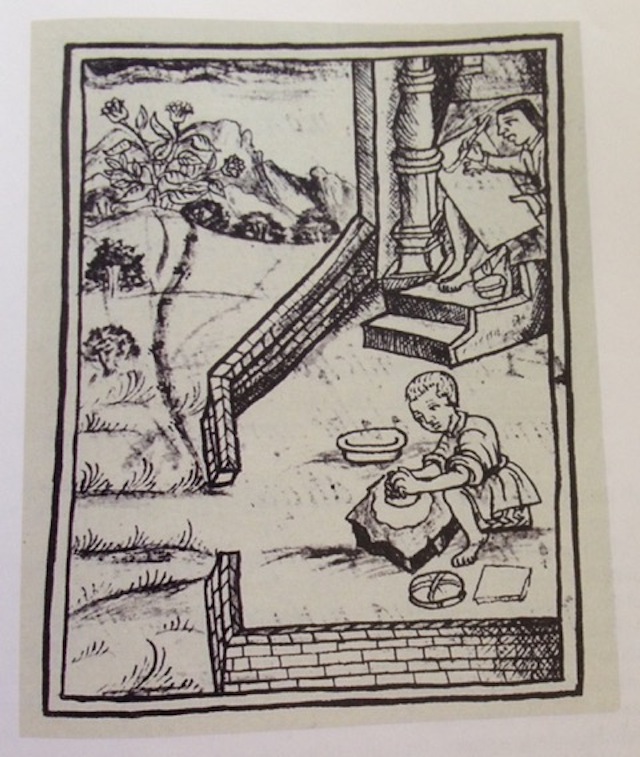

Sahagún identified by name the four indigenous “grammarians” and three scribes with whom he worked, but his illustrators remain anonymous. With meticulous attention to different artist’s techniques such as treatment of line, profiles and proportions of human figures, and how clothing was painted, Magaloni Kerpel identifies the hands of twenty-two painters at work in the Florentine Codex. Included in this number are four “well-trained” master painters. Based on their individual signature styles, Magaloni Kerpel names them Master of Both Traditions, Master of the Three-Quarter Profiles, Master of Long Noses, and Master of Complex Skin Coloring. In the case of the Master of Both Traditions, for example, Magaloni Kerpel argues that his figures show his mastery of both pre-Hispanic painting traditions and Renaissance techniques. But, even more tellingly, she observes how he used the two traditions to denote time and space – “indigenous past or the colonial present.” She also speculates that the painters may have represented themselves in the depictions of artists that appear in the Florentine Codex in Book XI, giving us an even more intimate sense of their individuality. Equally significant is her analysis (in collaboration with conservators) of the artists’ use of what she terms “symbolic colorants.” Colorants were made from both organic (plants, flowers, insects) and mineral pigments and both could be used to make similar colors. What mattered to the artists, however, were not just the colors but also their sources – from above the earth or below it –which endowed them with particular symbolic power. As Magaloni Kerpel argues, the images in the Florentine Codex should not be considered “as mere illustrations to the texts, but as self-contained visual narratives that sometimes revealed and sometimes concealed a world of their own.”

With a nuanced appreciation for the actual fabrication and materiality of the Florentine Codex, Magaloni Kerpel’s research is an outstanding example of scholars’ new approaches to the Florentine Codex. Paying attention to the illustrations as works of art and thinking about the codex as an artifact and not just as a text to be mined for information, helps us to understand in provocatively fresh ways not only its creation but also the cultural exchanges and collaborations unleashed by the Spanish conquest and its aftermath both locally and globally.

Works referred to and additional sources:

Diana Magaloni Kerpel, “Painters of the New World: The Process of Making the Florentine Codex” in Colors Between Two Worlds: The Florentine Codex of Bernardino de Sahagún, edited by Gerhard Wolf and Joseph Connors (Florence, 2011)

A video of a lecture by Diana Magaloni Kerpel

A digital version of the Florentine Codex can be accessed here and here.

An English translation of the Florentine Codex is available as Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, trans. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble, 12 volumes (Salt Lake City, 2012).

On Sahagún as an ethnographer, see Miguel León-Portilla, Bernardino de Sahagún: The First Anthropologist (Norman, OK, 2002).