Anyone who has been following college football over the last two to three years is aware of at least one case of a high-profile football player accused of sexual assault. It is has become an unavoidable topic. In part, that is because a fair number of cases have been reported in the media.

Here’s a sense of the scope in recent years. In 2015, there were allegations against players at Florida International University, the University of Tennessee, UCLA, and Santa Barbara City College. 2014 saw cases at Utah State, Kentucky, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Texas, Tulane, Bowling Green, Tulsa, Culver-Stockon College, Miami, Vanderbilt, Kansas, New Mexico, Ole Miss, and Eastern Washington University. In 2013, there were cases reported at Baylor, Brown, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Pacific University, Ohio State, Arizona State, Vanderbilt University, McGill University, Wisconsin, and the University of California, Los Angeles. In 2012, there were allegations against players at the University of Texas, Appalachian State University, Baylor, Old Dominion, Morehouse, and the US Naval Academy.

Football, though, does not have a monopoly on sexual violence. We are in a cultural moment where we are discussing sexual harassment, abuse, and assault throughout our society, including in the entertainment industry, the military, at university, at technology companies, and elsewhere.

And yet, despite the ubiquity of sexual violence, we often end up talking about it when it is perpetrated by college football players. There are plenty of reasons for this. Players have a high profile and, because of the money invested in them or their teams, people feel a certain ownership over them. Players are held in high esteem by fans or hated by fans of rival teams, and so their off-the-field behavior is either a shock or evidence of what we already knew. Players in legal trouble are often not able to play, which can have an effect on the team. Many athletes are African American, especially in football and, because of the racism that exists in and around the world of sports, the US media as well as the legal system often focus on crime when the perpetrators are black. At the collegiate level, there is a personal investment in the fandom from people who attended that school, who pour money into the institution, and who might see the players on their team representing themselves in some part.

On top of all of this, football is the most popular sport in the US. It makes a lot of money for a lot of people. College football is now second to the NFL in overall sports revenues. Universities are often financially invested in major sports, so officials—and highly paid coaches, making literally a hundred times what they earned forty years ago—have some motivation to absolve players and move on as if nothing happened.

This is not a new phenomenon or a recent development, however, despite the growth of the college football industry over the last few decades. I have collected a list of more than 115 cases of college football sexual assault allegations, stretching back to the mid-1970s.

Many of these cases involve multiple players. In all, approximately 40 percent of the cases I’ve studied are gang rape allegations involving multiple players. If you add in cases where teammates are witnesses or later accomplices in harassing the woman who reported the violence, that number creeps up to close to 50 percent. This is incredibly high compared to what is known about gang rapes in the overall population. In 2010, Sarah E. Ullman wrote about multiple-perpetrator rape based on research that provides a wide range of possibilities for how common gang rape is: “From under 2 percent in student populations to up to 26 percent in police-reported cases.” Granted, my research is unscientific and limited by my access to resources, but even if I am off by 10-plus percentage points, the rate of gang behavior in these cases is remarkable. These cases are collective experiences of violence and they suggest that it is necessary to take a long, critical look at the culture of football teams and the famous mystique of the locker room.

The caveat is that all of this data is based my own informal research. That the earliest I case I know of is from 1974 is arbitrary. Certainly there were football players accused of rape before that date (football has been around since the late 19th century). But my research, has been limited to keyword searches in nationally-circulated papers that are now indexed and online. I wonder what is still buried in the pages of local or regional newspapers from across this country that are accessible to people with the time and means to dig through the microfilmed versions.

Also, the idea that you could be raped by someone other than a stranger is a fairly new concept in and of itself. The term “acquaintance rape” first appeared in print in the late 1970s and didn’t go mainstream for another decade. A ripple effect of this is that sexual assault is woefully underreported, especially on college campuses. Finally, it’s much easier for me to locate cases from the last decade or so, since newspapers and TV stations began putting their content online. My Google alerts over the last three years have flagged cases that probably would have gone completely under my radar in the past. The list then is top-heavy over the last few years.

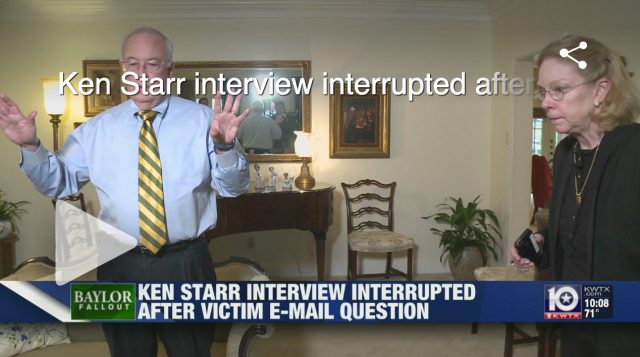

Ken Starr was forced to resign as Chancellor of Baylor University (after he had been demoted to that post from President) for the university’s mishandling of numerous rape accusations against football players and then for giving three different answers on camera to a question about whether he knew about a particular rape accusation. (The Atlantic)

What this list does show is that there is no such thing as an isolated case when we talk about college football and sexual assault. Each incident is embedded in a decades-long history that, unless something changes, will have an alarmingly robust future. And so, it’s important to think seriously about how to mitigate this problem. One way to do this is to stop focusing so intensely on the athlete and the person who reports them (there are already plenty of people who do that work). Instead, we need to interrogate the entire system, including coaches, athletic directors, universities, the NCAA, the police who investigate the crimes, and the media who cover it. What are they all doing to perpetuate this culture that minimizes and sometimes even encourages sexual violence?

For if we fail to continually and consistently ask the hard questions and accept their answers, I worry about how little things will have improved two, five, ten, or forty years from now.

More on the Baylor scandal by Jessica Luther can be found here at the Texas Monthly and here:

Dan Solomon and Jessica Luther, “Silence at Baylor,” Texas Monthly, August 20, 2015.

Jeff Benedict and Armen Keteyian, The System: The Glory and Scandal of Big-Time College Football (2013)

Jon Krakauer, Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town (2015)

“Sexual Violence on Campus: How Too Many Institutions of High Education Are Failing to Protect Students,” July 9, 2014, US Senate Subcommittee on Financial and Contracting Oversight.

Melissa McEwan, “Rape Culture 101,” Shakesville, October 9, 2009.

Sarah E. Ullmann “Multiple Perpetrator Rape Victimization: How it Differs and Why it Matters” in Handbook on the Study of Multiple Perpetrator Rape, eds. Miranda A. H. Horvath and Jessica Woodhams (2013).

Before Jessica Luther became a major author on women and sports, she was a graduate student in the History Department at UTAustin. You can find the articles she wrote for Not Even Past here:

Zeitoun by Dave Eggars (reviewed by Jessica Luther)