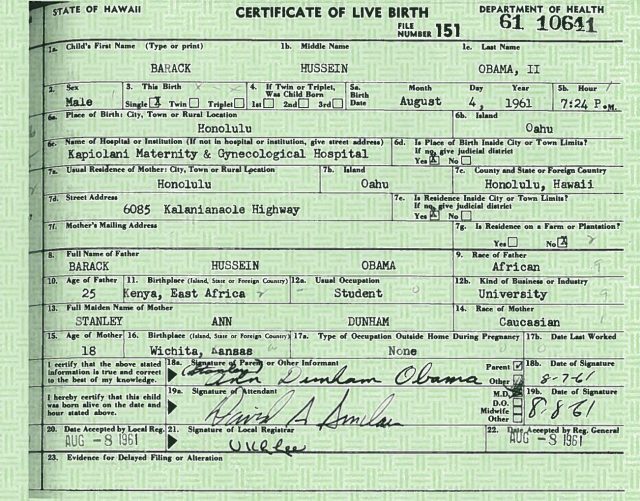

To me at least, the recent presidential election was all about history. Historians explored the precedents for what many called an unprecedented contest. Historical documents (such as President Obama’s birth certificate) became campaign talking points. The president-elect vowed to “Make America Great Again.” In an interview with the New York Times last March, he identified his favorite periods: The early twentieth century (the high tide of business-building and entrepreneurship, he said), and the 1940s and 1950s –when, in his words, “we were not pushed around, we were respected by everybody, we had just won a war, we were pretty much doing what we had to do.”

And then there was fake news and what it means for future historians.

Certainly it is doubtful that tomorrow’s historians will agree among themselves about the meaning of Mr. Trump’s victory. Some will see it as the logical culmination of forces set in motion in the 1970s and 1980s, when the emerging global economy brought prosperity to some Americans but left behind those who lost their jobs when companies took their production overseas or south of the U. S.-Mexico border. Other historians will push the timeline back further, and highlight technological innovations in the workplace that displaced employees in a variety of industries, leaving them stranded in distressed communities. Still other historians will focus on the rise of international terrorism; the demographic transformations wrought by immigration; conflicts between ethnically diverse urban areas and homogeneous (white) rural areas; the on-going culture wars over abortion and same-sex marriage; or negative attitudes toward the Washington political establishment. In other words, I can predict with some confidence that in the process of accounting for Mr. Trump’s appeal, historians will engage in a lively debate among themselves about the distant and recent past.

However, history is an evidence-based discipline, and what will happen if the evidence itself is in dispute? Historians will all agree that the election took place on Tuesday, November 8, 2016; that is a matter of chronological fact. Yet to draw some conclusions about the meaning of the election, historians must find and assemble evidence and present a coherent narrative, a story that will explain Donald Trump’s victory and Hillary Clinton’s defeat.

In discussing the nature of news today, we might return to the Jonathan Swift saying of 1710, “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it”; variations have been attributed to Mark Twain and others. Today Americans get their news from a variety of media, including Facebook and highly partisan TV cable networks and shows. A few decades ago, media observers were lamenting that our political discourse had been reduced to “soundbites” on the TV evening news; now those soundbites seem positively expansive when compared with the 140-character pronouncements unleashed on Twitter. The president-elect distrusts the news media; he wants no filter on his words; hence his determination to speak directly to his Twitter followers. Conventional media outlets can then report on his postings if they choose. (It was interesting to see so-called “lamestream” journalists as well as sites such as factcheck.org and politifact.com quickly dispute Mr. Trump’s claim that he won an electoral-college “landslide,” when in fact his margin of victory was 46th out of 58 presidential contests.) No doubt we as historians will have to show considerable resourcefulness in assembling a story about the past that relies not only on email messages but also on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat (these last two messaging apps). Although Snapchat is short-lived and self-deleting, someone could take a screenshot of a Snapchat posting and then email, tweet, text, or publish it. The sheer number of different means of communication can be overwhelming.

Websites run the gamut from legitimate, responsible news outlets, to highly partisan sites, to purveyors of fiction. This array presents a special challenge to journalists today as they craft the so-called first draft of history. These sites might or might not abide by the journalistic convention and rely on multiple vetted sources before publishing an article. And of course sensationalism defines many of these sites. In the three months running up to the election, according to a study by Buzzfeed, the “top fake election news stories generated more total engagement on Facebook than top election stories from 19 major news outlets combined.” These fake stories included the claims that the Pope had endorsed Donald Trump and that Hillary Clinton sold weapons to ISIS.

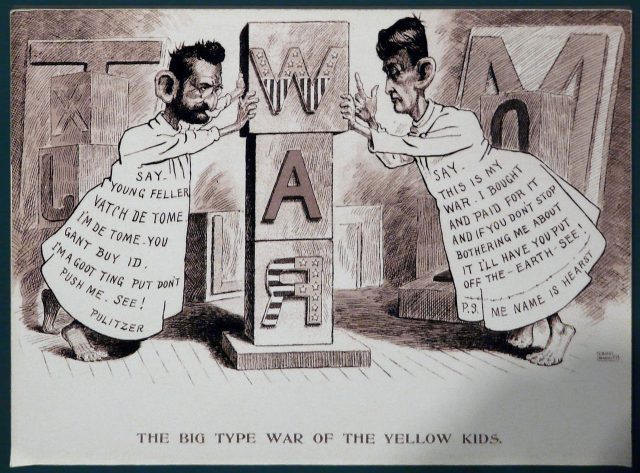

William Randolph Hearst was not the first publisher to discover that lurid and fake stories sell lots of newspapers, and his descendants in the business have brought a high-tech sensibility to the enterprise. This presidential election represents a new chapter in the commodification of news—or rather, in some cases, of fiction—as whole websites with official sounding names like USADailyPolitics.com became “clickbait” for some Americans. Advertisers are drawn to sites that are popular, and pay to place their ads on those sites, enriching the storytellers. Resourceful people in the U. S. and abroad made tidy sums by running articles that Hillary Clinton’s criminal indictment was imminent: Read All About It!

So what’s a historian to do? First of all, we have an obligation to our students to teach them how to evaluate evidence– to consider the source as well as the context, and to seek multiple sources that confirm an assertion– a skill that will serve them well in the classroom but also after college, as they become responsible, informed citizens. Second, we have an obligation to the historical profession to uphold traditional standards of excellence by adjusting our research methods to account for, on the one hand, the proliferation of all kinds of useful information online, and, on the other, the fact that some of that material is less than trustworthy. And finally, we must continue to prize nuance and complexity over simplistic explanations.

Still, we live in perilous times for historians and others in fact-based disciplines. President Obama released his long-form birth certificate in April, 2011, but that document (combined with other evidence about his childhood in Hawaii) did not convince a substantial minority of Americans that he was indeed born in the United States. For some, truth is contingent on one’s gut feelings. Indeed, in November, 2016, the Oxford English dictionary declared as the “word of the year” the term “post-truth,” defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” If we do live in a “post-truth” age, historians of the future will truly have their work cut out for them.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.