Guns and America enjoy a symbiotic relationship, the one constantly evoked when you refer to the other. A Congressional Research Service report estimated that, in 2009, the number of firearms in the United States surpassed the number of people, 310 million compared to 306.8 million. That gap has continued to widen, and as of 2015, guns outnumbered people by 40 million. These aren’t exact figures; more concrete numbers are hard to come by. Still, they show that the number of firearms in the US, by an reasonable estimate, dwarfs that in any other country in the world. In the list of gun-loving nations, the United States has nearly twice the number of guns per capita as the next country, Serbia.

Guns and America enjoy a symbiotic relationship, the one constantly evoked when you refer to the other. A Congressional Research Service report estimated that, in 2009, the number of firearms in the United States surpassed the number of people, 310 million compared to 306.8 million. That gap has continued to widen, and as of 2015, guns outnumbered people by 40 million. These aren’t exact figures; more concrete numbers are hard to come by. Still, they show that the number of firearms in the US, by an reasonable estimate, dwarfs that in any other country in the world. In the list of gun-loving nations, the United States has nearly twice the number of guns per capita as the next country, Serbia.

How do we explain this? How did the US become such an outlier? Many point to the Constitution and the second amendment, the right to bear arms folded into the fabric of our nation almost from its inception. Guns were what fueled westward expansion, and the citizen militia is what beat back the British. Therefore, the gun holds a spot of preeminence in the national lore of America.

Pamela Haag’s book The Gunning of America: Business and the Making of American Gun Culture, offers a meticulously researched and beautifully written corrective to this mytho-poetic view of the gun. Haag, who received a PhD in history from Yale, takes the old journalistic maxim of “follow the money” and applies it to the American gun industry. As she writes, “We hear a great deal about gun owners, but what do we know of their makers?” This is the guiding light of her book: to trace the development of the gun industry and the loose constellation of entrepreneurs who laid the foundation for what we have today. These were men like Oliver Winchester, Samuel Colt, and Eli Whitney (yes, that one).

Haag’s overall argument is that it was the gun industry itself that turned the United States into a gun-loving nation. To begin her book, she points out what many gun enthusiasts themselves have been saying for years, albeit selectively and ahistorically: that guns were tools, used and marketed as such. They were unremarkable objects, with as much emotional resonance as a claw hammer or a bow saw.

Coupled with this reputation as ordinary and functional was a style of production that limited the number of guns that could find their way to the market. Guns were originally made by blacksmiths, few of whom specialized in manufacturing firearms, and were therefore often clunky items, prone to breaking and difficult to repair.

Two Pennsylvania rifles. Rifles like this were used by militiamen and snipers during the American Revolutionary War (via Wikimedia Commons).

Eli Whitney was among the first to propose a solution to this problem. In 1801, he made a presentation before President John Adams, demonstrating the merits of constructing guns out of interchangeable parts. This approach would enable him to quickly produce a large number of reliable firearms that could be easily repaired.

This development is what made the modern gun industry viable and other manufacturers soon followed Whitney’s lead. It was not a very stable market, though. The gun business was largely tethered to the boom and bust cycle of war, with the United States government serving as its largest client. In times of peace, manufacturers turned to the overseas market, selling weapons to whichever foreign government happened to be in need of them.

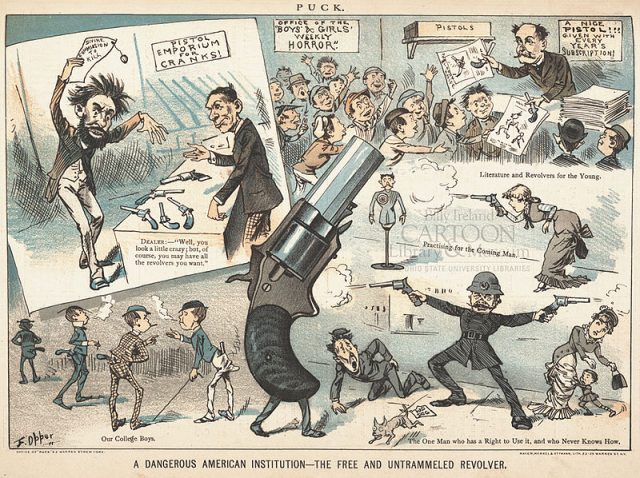

But in order to expand their business, the gun manufacturers knew that they had to increase the domestic demand for their product. Through a close look at advertisements and items like dime-store Westerns, Haag brilliantly demonstrates how savvy marketing transformed the gun from a tool to an emotionally-charged emblem of masculinity, individualism, and the nation. As she writes, “what was once needed now had to be loved.”

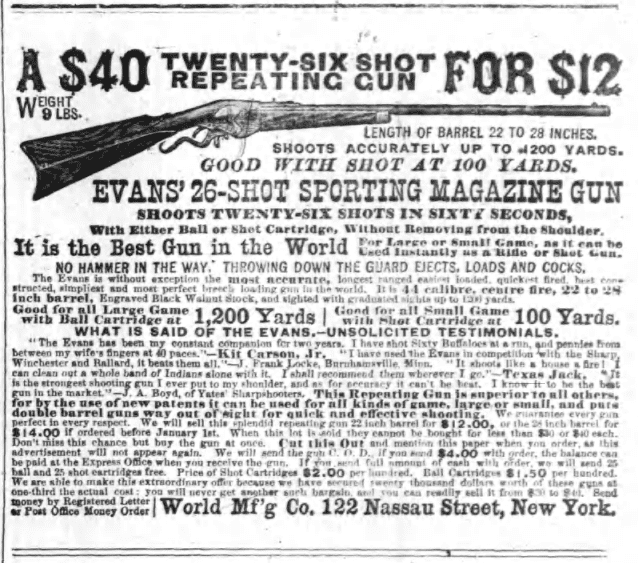

In the earliest examples that Haag chooses, guns are listed as just one of many items that your local smithy could make and repair. Later ads would grow more sophisticated, but they would still focus on mechanical virtues and overall utility.

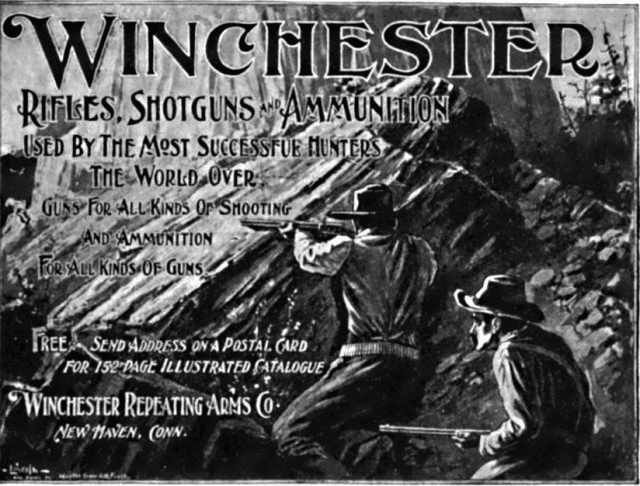

This began to change in the early 1900s, as the gun manufacturers switched from their previous text-heavy ads to more emotive, visual ads, rendered in full color and often regarded as works of art in themselves. They depicted excitement, romance, and nostalgia, drawing heavily on images of cowboys and hunters in the Wild West, their trusty firearm at their side as they faced down a vicious bear or band of Native Americans.

The manufacturers didn’t stop at wannabe woodsmen. They sought to make their market as wide as possible, and in doing so made the gun seem an integral part of American life and history. A key part of this process was to make owning a rifle synonymous with manhood, targeting the father-son relationship in particular. “You know [your son] wants a gun,” one ad reads,” but you don’t know how much he wants it. It’s beyond words.” Another tells fathers that a boy’s “yearning for a gun demands your attention. He will get hold of one sooner or later. It is his natural instinct.”

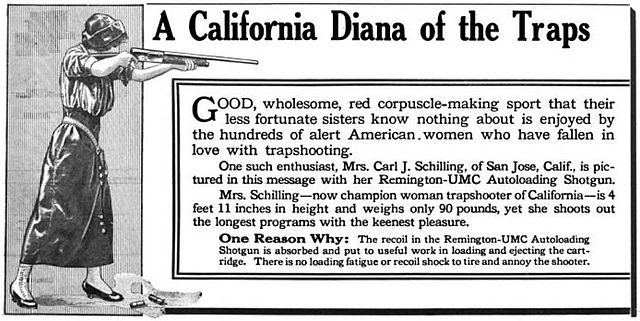

But guns weren’t the sole province of men. An ad for Smith and Wesson read, “Any woman can learn how to use a Smith & Wesson in a few hours, and . . . she will no longer feel a sense of helplessness when male members of the family are absent.” A Winchester ad from 1921 proclaimed that “Every man, woman or child has an inherent desire to own a gun.” Advertisements like these, alongside their countless depictions in popular culture, are what created America’s gun culture.

Juxtaposed with the account of these early arms manufacturers is that of the women associated with them, and in particular Sarah Winchester, who married Oliver Winchester’s only son. Sarah led a singularly unhappy life. She lost her first daughter, Annie, when the child was only 40 days old. She’s believed to have suffered one or two more miscarriages, and she lost her husband to tuberculosis, and, shortly after, her mother also died.

At this point, Haag’s account drifts into speculation. She theorizes that Sarah thought herself cursed, haunted by the victims of all the guns that her husband and father-in-law brought into the world and thanks to whose money she lived in splendor. In a possible attempt to ward off the spirits she built the Winchester mystery house in San Jose, California, a vast mansion that she was perpetually making additions to, with stairs that lead to nowhere and rooms, fully furnished and decorated, that are completely walled off. Now a tourist attraction, it stands as an architectural depiction of madness.

This is fascinating stuff and it’s readily apparent why Haag thought it necessary to counterpose her depiction of the gun manufacturers, who have all the humanity of adding machines and clearly distanced themselves and their capitalist aims from the visceral reality of the violence of the arms they made, with the almost unbearable humanity of Sarah Winchester. The one drawback is that because it is so highly speculative, this part of the book runs the risk of detracting from the brilliant research that Haag deploys elsewhere.

And the research really is quite brilliant. Haag gained access to the company archives of Winchester, Colt, and other gun manufacturers, and she makes excellent use of the privilege. Haag is a beautiful writer, able to weave together a compelling narrative studded with memorable lines and anecdotes, like the gun salesman in Turkey who, upon realizing during a demonstration that his gun was clogged with sand, solved the problem by urinating on the offending component.

In the end, Haag strips away the mythology of guns in America to reveal a truth that’s both more ordinary and more profound than what existed before. It was the ineluctable logic of capitalism that drove the original gun manufacturers to seek out as wide a market as possible for their product, and it was the story that they told their customers that has lived on until today.

Pamela Haag. The Gunning of America: Business and the Making of American Gun Culture. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

![]()

Also by Isaac McQuistion on Not Even Past:

Examining Race in Appleton, WI.

You may also like:

Kalashnikov’s Lawn Mower: The Man behind the Most Feared Gun in the World.

![]()