Change.org, Ipetition, petitiononline — today, the digital marketplace has spurred the easy distribution of petitions. While they are significant, modern petitioning campaigns offer a different contribution to public discourse than their nineteenth-century counterparts. For women, people of color, and others who had little access to political movers and shakers, petitioning placed them a signature and postage stamp away from the eyes and ears of legislators. Petitions provided grounds to begin a range of other campaigns and simultaneously created a network of canvassers and petitioners.

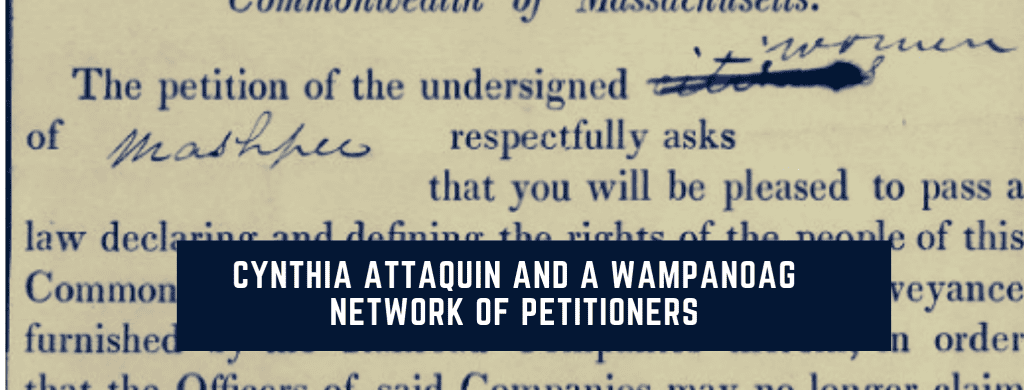

In 1842, Cynthia Attaquin and 13 other female residents of the Mashpee, a Wampanoag tribe on Cape Cod, petitioned the Massachusetts State Senate to clarify laws regarding the passage of people of color on railroads. Their petition represented a community of color with very specific motivations and understandings about what can come with organized petitioning efforts.

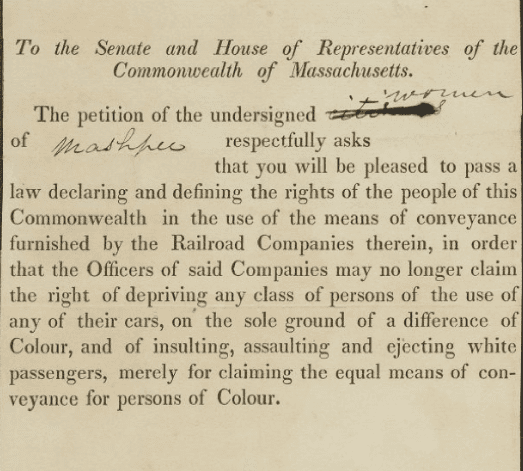

The text of the petition, likely printed in a widely distributed newspaper, requested the legislature to “pass a law declaring and defining the rights of the people [of Massachusetts] in the use of the means of conveyance furnished by the Railroad Companies… in order that the Officers of said Companies may no longer claim the right to depriving any class of persons the use of any of their cars, on the sole ground of a difference of color…”

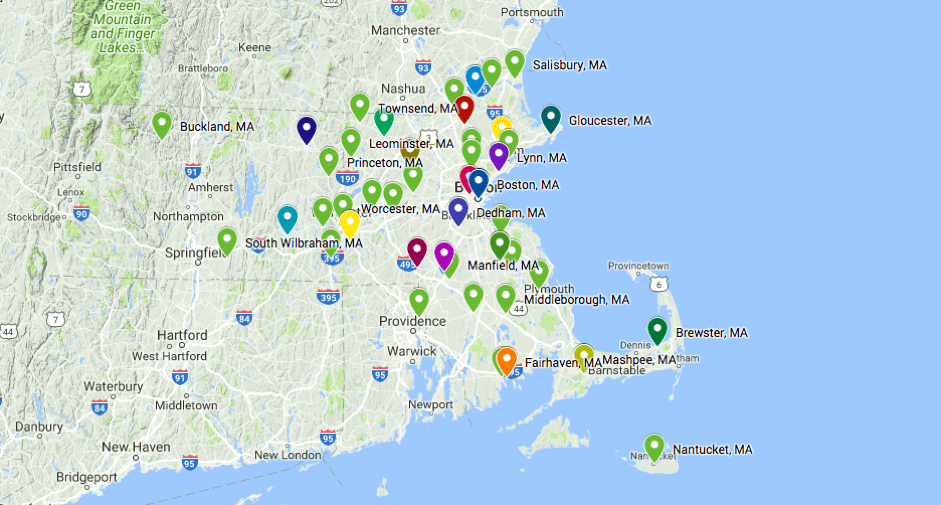

For several years in the mid-nineteenth century, Congress established a “gag rule,” immediately tabling all abolition-related petitions. However, the focus of this particular campaign was local, and Attaquin’s was one of sixty sent to the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1842 on the topic of clarifying railroad regulations. In total, 5129 individuals participated in this petitioning campaign (Map 1).

State representatives responded with Senate Bill No. 9 and 10, which proposed to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color on railroads and remove a clause in the state constitution outlawing “intermarriages of different races and complexities.”[1]This campaign is a great example of successful, local mobilization efforts by canvassers, however, it was not unusual. According to Colin D. Moore and Daniel Carpenter, “women canvassers garnered 50% or more signatures than men while circulating the same petition requests in the same locales.”[2] Additionally, as Manisha Sinha and others have argued, people of color were instrumental in advocating for their own social and cultural place in the United States. Native women were no different.

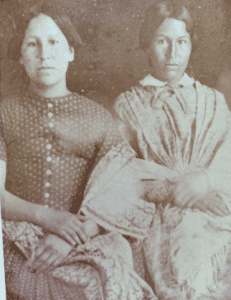

While the campaign itself is interesting, what is more compelling are the signers: the petition submitted by the “women of Mashpee” was signed entirely by women of color.[3] The first signer, likely the canvasser, or the individual who encouraged others to sign, was Cynthia Conant Attaquin, originally from Plymouth. According to 1860 and 1880 census data, Cynthia was married to and lived with Solomon Attaquin, Mashpee’s first postmaster. Their racial classifications fluctuated between “Indian” and “Mullato,” but they were listed as members of the Indian tribe in official reports to the state department responsible for managing the Mashpee. Census data confirms that both Cynthia and Solomon were literate and could speak fluent English, making it even more likely she was the canvasser. Though in their 30s and recently married, both gained social prominence in Mashpee because of their relationship to other high standing elders, particularly, Ezra and Solomon Attaquin, Solomon’s father and grandfather. Familial ties to political and tribal leadership could also explain the involvement of four other Attaquin women in the petition: Betsy J. and Martha (Solomon’s sisters), Desiah (Solomon’s paternal grandmother), and Leah (Solomon’s aunt and wife of Ebenezer Attaquin).

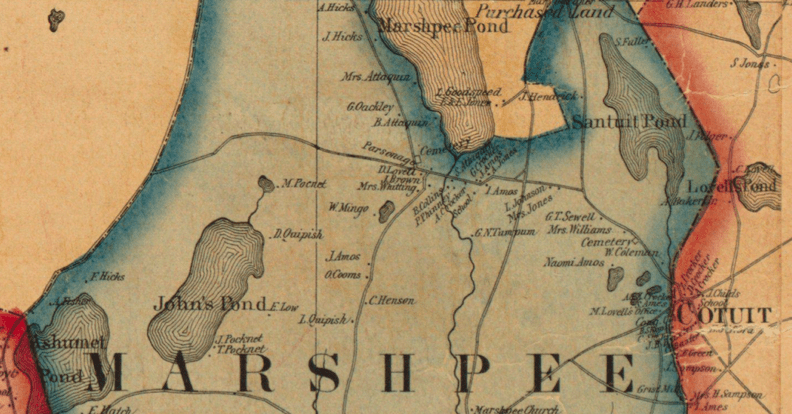

Additional signers included Achsah R. Jones (also spelled Axah), identified in the census as either Black or Indian, Martha Simmons who was 59 at the signing, Ruth Coombs, Ruth Kurt, Ophelia Ceasar, whose family lived next door to Benjamin Attaquin (Solomon’s brother), Sarah (Wickums) Barney, and finally, Abigail (Wickums) Amos, who married either Joseph or Josiah Amos. In an 1858 map of Barnstable County (below), one can note the proximity of “S. Attaquin,” ” J. Amos,” “Mrs. Jones,” “B. Attaquin,” and others just off what is still Main Street facing the Mashpee Pond. (See map 2).

One is left to wonder the motivations of the female actors in this narrative. Seeing as many of them were literate, had they read of the call for petitions in the newspaper or heard tell of an abolitionist circular? Did they see themselves immediately impacted by the cause? And once Cynthia decided to sign her name onto this petition, did she walk down Main Street, stopping at each of her family member’s and friend’s homes convincing them of the potential for positive repercussions? Or did they meet up somewhere, possibly the Indian Meeting House, the parsonage (also on Main Street), or even the Attaquin Hotel? What is certain is the imprint of their participation on the town of Mashpee. Local histories like Earl Mills’s Son of Mashpee: Reflections of Chief Flying Eagle, A Wampanoag recall that the legacies of the Amoses and Attaquins remained stamped on the town even after the campaign.[4]

Solomon and Cynthia were known to have opened the famous Attaquin Hotel that often doubled as the town’s post office and that hosted government officials and diplomats. They were also heavily involved in a previous petitioning campaign for tribal rights. The recently married Attaquins were active participants in what would be called the Mashpee Revolt, a peaceful protest in response to unfair exploitation of Mashpee land and frustrations with the guardianship. Led by a Methodist preacher and Pequot Indian named William Apess, a 1833-34 petitioning campaign and protest resulted in the reclamation of Mashpee self government. The revolt’s primary petition from the Wampanoag contained a total of 287 signatures of men and women living in Mashpee including Ophelia Caesar, Betsey Attaquin, and Martha Simmons. By 1842, Cynthia and others in Mashpee were well aware of the potential in petitioning, and their effort drew on a well-established network of Native American petitioners.

The pattern of Cynthia Attaquin’s petition affirms what many scholars have pointed to, which is firstly, the importance of social networks and kinship ties to mobilization; secondly, the presence of women and people of color writing their own histories; and finally, the importance of indigenous petitioning efforts. Native peoples continue to petition the government. In 2016 a Change.org petition by a 13 year old member of the North Dakota Sioux Tribe to protect waterways on the Standing Rock reservation gathered over 560,000 signatures and this month a petition for the UT Austin Native American and Indigenous Student Space Collective also circulated. In 1996, Chief Flying Eagle, Earl Mills Sr., of Mashpee summed up the importance of petitions to Native peoples:

Mashpee was different in the past and is still different today from other towns in the Cape. Our presence, the Wampanoags’, and the influence of our culture here, have made the difference. This small community and the United States have gone through similar stages of development. In many ways Mashpee is a microcosm of this country. To understand Mashpee is to understand our society better.[5]

[1] State Library of Massachusetts, Senate Bill No. 9 and 10.

[2] Daniel Carpenter, Colin D. Moore. “When Canvassers Became Activists: Antislavery Petitioning and the Political Mobilization of American Women”. American Political Science Review. Vol. 108, No. 3 (August 2014): 481.

[3] Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, Boston MA, 2015, “Senate Unpassed Legislation 1842, Docket 11057, SC1/series 231, Petition of Cynthia Attaquin”. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FHCL:11858184

[4] Sr, Earl Mills, and Alicja Mann. Son of Mashpee: Reflections of Chief Flying Eagle, A Wampanoag. 1st edition. North Falmouth, Mass: Word Studio, 1996, 12.

[5] Sr, Earl Mills, and Alicja Mann. Son of Mashpee: Reflections of Chief Flying Eagle, A Wampanoag. 1st edition. North Falmouth, Mass: Word Studio, 1996, xi.

Also by Alina Scott on Not Even Past:

Missing Signatures: The Archives at First Glance

You may also like:

A Historian’s Gaze: Women, Law, and the Colonial Archives in Singapore by Sandy Chang

Secrecy and Bureaucratic Distancing: Tracing Complaints through the Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive by Vasken Markarian

Justin Heath reviews Peace Came in the Form of a Woman by Juliana Barr (2007)

Mapping & Microbes: The New Archive (No. 22) by Christopher Rose