By Lydia Pyne

In 1873, there weren’t very many options for the public in the United States to see what a real whale looked like.

The occasional whale could wash up on a beach somewhere, of course, but it would rapidly begin to shuffle off its mortal coil, leaving beachgoers with the decidedly unpleasant process of natural decomposition. On the other hand, seeing the animal’s skeleton neatly hung in a museum was a bit incomplete because it required imagination or an artist’s reconstruction to put muscle and skin on the whale. Unlike other large mammals, whales can’t be taxidermied; consequently, stuffed whales weren’t part of the dioramas of charismatic megafauna installed in natural history museums at the turn-of-the-twentieth century. And photographing whales underwater – to see real whales in their natural habitats – was almost a full century away.

So, in 1873, the best possibility for people to see real whales was thanks to Great International Menagerie, Aquarium, and Circus, that touted its exhibit of “A Leviathan Whale, a grand and magnificent specimen, the King of the Deep” as “the only show in the world that exhibits a WHALE,” per then-contemporary newspaper articles.

By WHALE, the Menagerie meant a real, actual dead whale. This WHALE was quasi-preserved through the constant injection of chemicals and carted around via rail from one American town to the next in a bit of Music Man-like showmanship. Their competitor, the Burr Robbins Circus, exhibited a giant paper-mâché whale a few years later, determined to not be outdone by the Menagerie. The two whales dueled their way across the United States for the better part of a decade, vying for publicity, audiences, and the money to be made from the venture. And the Menagerie’s WHALE was all about just that – turning the public’s awe and wonder at nature’s unknown into spectacle for profit.

Whether visitors knew anything about whales after they had visited the Menagerie was irrelevant. The showmanship, the bustle of activity, the anticipation of the WHALE was something so singularly extraordinary, that it never failed to draw huge crowds. And, yet, the decades-long success of the traveling WHALE largely depended on the experience being personal. Step right up, ladies and gentlemen, and see for yourself. You know what a real whale looks like now because you saw one here and paid for the privilege to do so. It’s as though the Menagerie was able to curry a sense of authenticity or even expertise about whales since that was, technically, what visitors saw.

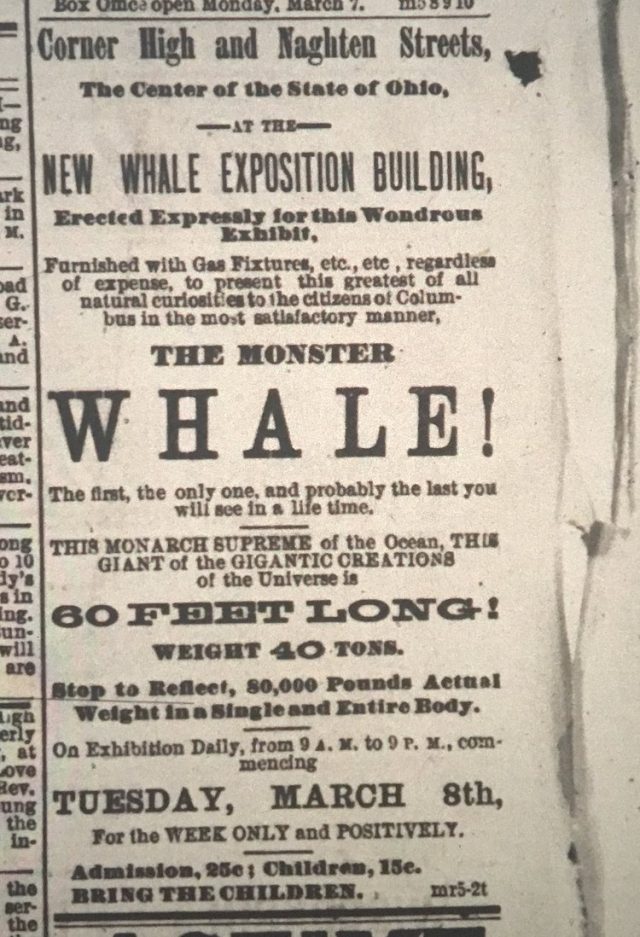

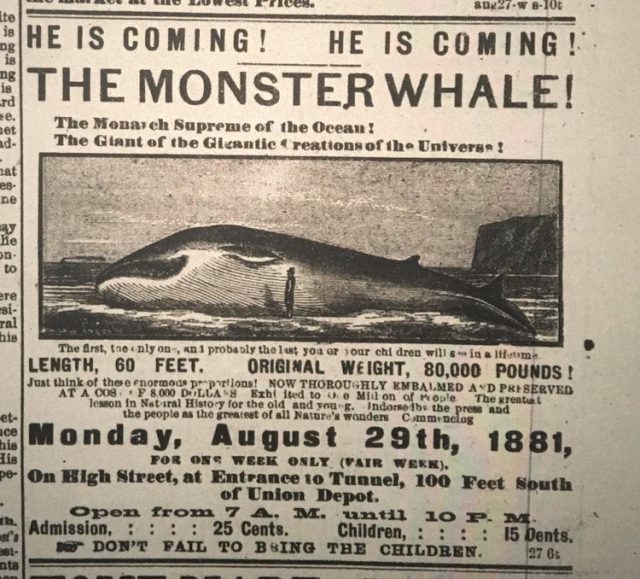

But the WHALE lacked scientific or natural history context. For example, when the Menagerie’s King of the Deep arrived in Columbus, Ohio, on March 8, 1881, the headlines from the Columbus Evening Dispatch sensationalized the exhibit, “He is coming! He is coming! The Monster Whale! The Monarch Supreme of the Ocean! The Giant of the Gigantic Creation of the Universe! Don’t Fail To Bring The Children!”

The exhibit and its publicity were as big as its cetacean. “It requires a great deal of elbow room, because his whaleship is sixty feet long in the clear,” the Columbus Evening Dispatch reported. Visitors invariably wanted to know how the exhibit was possible – exactly how the whale’s entrails were removed and replaced with first ice and then chemicals, how the sawdust underneath the whale corpse kept the leviathan’s leaking in check. How yet more chemicals applied to the whale’s skin kept the outer parts of the animal from decomposing and how iron hoops within the body cavity kept His Whaleship from collapsing in on himself. (The Dispatch assured its readers that the exhibit was “free from unpleasant odor.”) In short, the WHALE wasn’t really so much about whales inspiring awe and wonder in nature, so much as it was about how the WHALE’s keepers and revenue collectors had so effectively cheated the animal’s mortal decay.

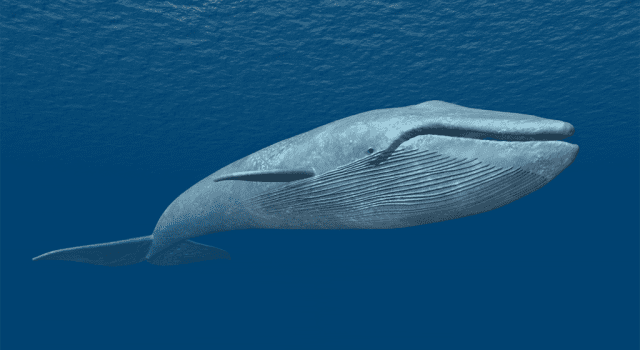

D. Finnan, Blue Whale, American Museum of Natural History

Meanwhile, in the museum world, curators, scientists, and exhibitors began to push to “properly” introduce audiences to the life, history, and biology of whales. The 1907 blue whale model at the American Museum of Natural History was built out of iron, wood, and canvas, and was eventually covered with a very believable paper-mâché exoskeleton of sorts. “They are building a whale at the Museum of Natural History,” the Wilkes-Barre Record of Pennsylvania reported on January 4, 1907, “from wooden strips, iron rods, piano wires, paper, and glue. They are carpenters, horsesmiths, and wallpaper hangers and when the work has been done in rough, the naturalists will give the finishing touches.”

Even though this wasn’t a “real” whale – it was a model – it represented the best knowledge about whales that the scientific community could offer at the beginning of the twentieth century. And as curators and showmen found, there’s only so much whale authenticity that audiences were willing to tolerate – no leaking, dripping, or smelling – even if those details are just as “real” as the other parts of an exhibit.

Rather than spectacle, credible institutions like the American Museum of Natural History argued, audiences ought to have accuracy. Scientific accuracy, to be precise. Unlike the free-wheeling world of sideshows, museums run by conservators, curators, and biologists could offer scientifically modeled and expertly credible specimens.

Understanding the Blue Whale (National Geographic)

Both sorts of whales – the menagerie act and the model in the American Museum of Natural History – have real and less-than-real parts to them: neither is in its natural habitat. So what makes one of these fake whales more real than the other? The intent? Its manufacture? The materials? What visitors take away? Some combination of everything? Both whales made audiences consider what was real, what was authentic, and how each aspect of the whales changed over time.

Each of the genuinely fake whales from the Great International Menagerie and the American Museum of Natural History balanced a series of tradeoffs in cost, audience, and realness. Whether or not history considers each authentic – or if that could change in the future – is an open question.

The stories of these whales are retold, here, as they appear in my book, Genuine Fakes: How Phony Things Teach Us About Real Stuff (Bloomsbury, Sigma, 2019.)

Noah Charney. The Art of Forgery: The Minds, Motives and Methods of the Master Forgers. London (2015).

Historian Noah Charney takes up the question of fakes, frauds, and forgeries; his book traces truly fantastic stories and offers a perspective from art history as to the cachet that fakes carry.

Byung-Chul Han. Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese. Translated by Philippa Hurd. Bilingual edition. (2017).

“Shanzhai” is a contemporary Chinese neologism that means “fake” and in this longform essay Han discusses all of the ways that “fakes” can exists — from copies to replicas to counterfeits to facsimiles. Every object, every fake, take on a life of its own.

Michael Rossi. “Fabricating Authenticity: Modeling a Whale at the American Museum of Natural History, 1906–1974.” Isis 101, no. 2 (2010): 338–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/653096.

———. “Modeling the Unknown: How to Make a Perfect Whale.” Endeavour 32, no. 2 (June 2008): 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endeavour.2008.04.003.

Michael Rossi’s work is key for anyone who want to dig into the specific details of the AMNH whale models.

Kati Stevens. Fake. Object Lessons. (2018).

In Fake, Kati Stevens offers a contemporary read on how “fake” has become a label, a judgement, and a moral judgement in the twenty-first century.

Erin L. Thompson. Possession: The Curious History of Private Collectors from Antiquity to the Present. (2016).

Possession traces the afterlives of antiquities and all of the many and bizarre ways that they’ve been collected and valued over millennia.

Header Image Credit: Richard Lydekker, Sperm Whale Skeleton 1894 (Wikipedia).