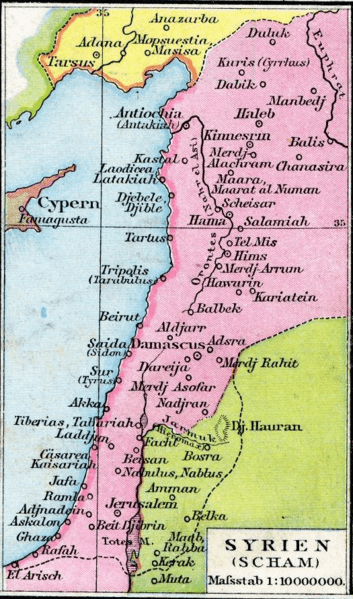

Cyrus Schayegh addresses the spatial formation of the modern world in The Middle East and the Making of the Modern World. He uses the history of Bilad al-Sham from 1830 to 1945 as his case study. Bilad al-Sham, also known as the Levant or Greater Syria, is roughly bordered by the Mediterranean to the west, Anatolia to the north, the Euphrates to the east, and the Arabian Peninsula to the south. It is comprised of the modern states of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine. Schayegh describes Bilad al-Sham as a “meso-region,” a relatively uniform area that is larger than a single nation but smaller than a continent. Although the meso-region of Bilad al-Sham is not homogenous, with ill-defined and fluctuating borders, it is comprised of interlinked cities and rural areas with a shared history.

Schayegh sees the meso-region of Bilad al-Sham as an ideal candidate for his central concept, “transpatialization,” which he defines as the “socio-spatial intertwinements” of cities, nation-states, regions, and global networks. He prescribes transpatialization as a remedy to histories that overemphasize a single scale of history, whether global, regional, national, or municipal. Transpatialization is a way to consider multiple scales of history simultaneously, providing a more complete picture of modern developments. Schayegh implements it to study the individuals, cities, and nation-states of Bilad al-Sham and connect the entire region to global trends. He argues that applying this concept to meso-regions, like Bilad al-Sham, is the most effective means of understanding developments in modern history.

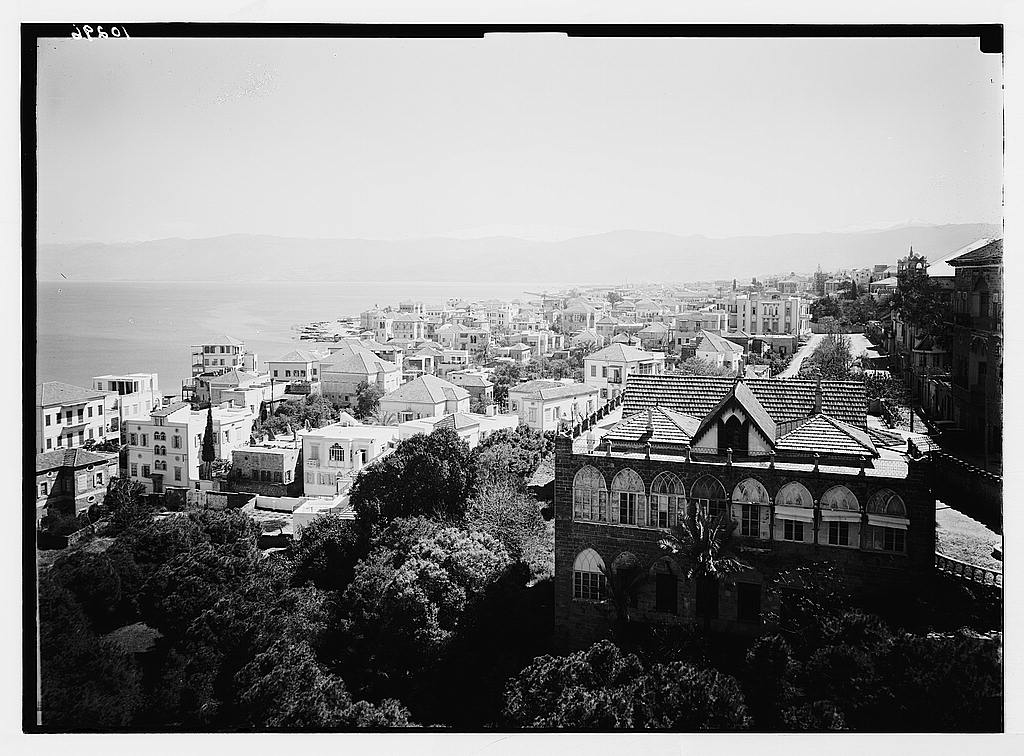

Applying transpatialization to the making of the modern Bilad al-Sham, Schayegh argues that there were two stages in its modern history. During the first stage, from the 1830s to 1910s, there were three primary socio-spatial intertwinements: Bilad al-Sham and the Eurocentric world economy, Shami cities and their inter-urban ties, and interregional transformation. Schayegh’s first stage is conceptually cogent, effectively explaining the economic and cultural development of the region. Although Schayegh notes the role of individuals living in Bilad al-Sham, cities are the primary characters and Beirut is arguably the most important character. Schyageh’s application of transpatialization is most apparent with Beirut. The city came to prominence during the nineteenth century for its role as a port city, connecting the interior cities of Damascus and Aleppo to the Eurocentric maritime economy. Likewise, the city benefited from its interregional relationship with Anatolia and the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, leading to its assignment as the capital of its own providence in 1888. Schayegh also notes individuals living in Beirut during this period such as Butrus al-Bustani (1819-1883) who was instrumental in the Arab Nahda, a cultural and linguistic renewal founded in the publication houses of Beirut. Bustani, like the city he inhabited, developed his ideas at the confluence of different scales of history. Schayegh points to the city of Beirut, its residents, its inter-urban ties, and its economic development to describe the first stage of modern Shami history as one of rapid transformation.

The second stage of modern Shami history is the primary focus of the book, where Schayegh applies transpatialization to the transitional period of the Ottoman Empire during the 1920s and the development of nation-states during the 1930s and 1940s. He argues for the development of a “national umbrella” out of what was previously described as a “patchwork region.” Instead of attributing the rise of nation-states to globalization, the decisions of powerful individuals, or any other singular narrative, Schayegh ties together all relevant factors—the Great Depression, Jewish migration, European geopolitical strategy, Arab nationalism, and more. During the second stage, Schayegh records the accentuated build-up of nation-states in the region, which were influenced by innumerable factors. One particularly influential factor was the development of economic competition between the port cities of Haifa and Beirut. Schayegh notes the individuals, communities, cities, and nations that influenced this competition. He argues that this contest, primarily between Syrian and Yishuv communities, played a significant role in the development of competing national identities in the region. Schayegh’s concept of transpatialization convincingly entwines global, regional, national, and municipal histories to provide a nuanced account of nation-state development in Bilad al-Sham.

Schayegh’s concept of transpatialization weaves together Bilad al-Sham like a tapestry. The intertwinement of local, urban, regional, and global fields presents views of the modern Middle East that are otherwise unapparent. For example, transpatialization brings new meaning to consequential topics like the development of Arab nationalism. It captures the fluctuating values of qawmiyya (pan-Arab nationalism) and Wataniyya (individual state nationalism) as individuals, cities, nation-states, and regions appropriated them. This leads to novel formulations like Syrian president Shukri al-Quwatli’s: “I am a son of Damascus including all its neighborhoods, its different quarters and houses, I am a son of Syria, and I am a son of the Arabs.”

Schayegh uses transpatialization to effectively trace some historical developments like Arab nationalism, but his attempt to offer a definitive history of Bilad al-Sham’s spatial formation is incomplete. For instance, he misses opportunities to address global networks. He mentions diasporic communities and individuals, like the Homsis in Sao Paolo and Khalil Sakakini in New York, yet fails to significantly develop these global connections into his argument. Most of his analysis remains within the bounds of Bilad al-Sham despite his global ambitions.

Schayegh pulls together a magisterial account of the modern formation of Bilad al-Sham and sets a precedent for the use of transpatialization in global history. While the argument of the book is often specific to Bilad al-Sham, it is a useful work for a broad audience seeking conceptual tools to make sense of the modern world. The concept of transpatialization is viable and should be employed in future studies of Bilad al-Sham, the modern Middle East, and the modern world.

Carter Barnett studies the history of medical institutions in the 19th/20th-century Middle East. He received his BA in History and Arabic from Baylor University and an MA in Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Texas at Austin. His MA thesis examined the ambivalent interaction between missionary medicine and Palestinian society, politics and law. In 2022, he joined Johns Hopkins History of Medicine doctoral program. His present research takes interest in the history of (post)colonial medical institutions in the Middle East, focusing on the intersections between religion, international health organizations and changing medical practices.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.