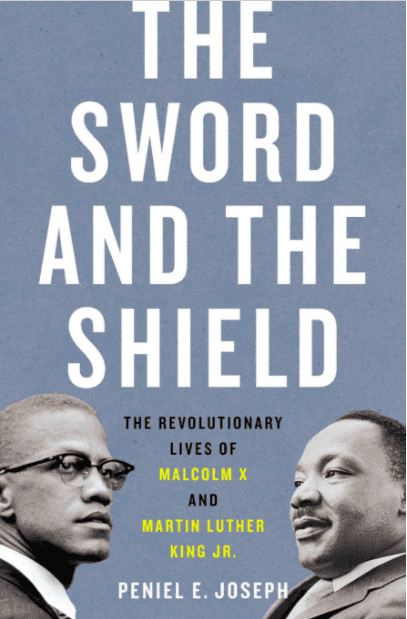

This is Part I of a conversation with Dr. Peniel Joseph. In this conversation, Dr Joseph discusses his new book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. This dual biography of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King upends longstanding preconceptions to transform our understanding of the twentieth century’s most iconic African American leaders. The Not Even Past Conversations Series was born out of the extraordinary circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. It takes the form of an interview held informally (usually at home) over Zoom with leading scholars and teachers at the University of Texas at Austin and beyond. The following is a lightly edited transcript of a conversation between Adam Clulow and Peniel Joseph.

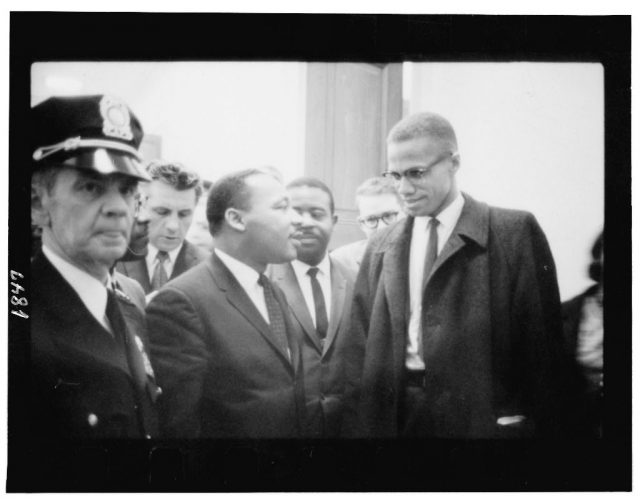

AC: Thank you so much for joining me today. You start the book with a meeting that takes place on March 26, 1964, between Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Remarkably, and as you write, this is the only time they actually met. Can you tell us about this meeting and how it came about? And the bigger question that runs through the whole book is how should we characterize their relationship? You use a few different terms. You talk about them as political partners, kindred spirits, and alter egos. How should we understand this meeting and their relationship more generally?

And do you think at that moment in March 1964, they’re aware of this partnership? They’re clearly thinking about each other. They’re reading each other’s writing. They’re listening to each other’s speeches now. They’re intertwined in all sorts of fascinating and productive ways but at this moment of meeting, is there an awareness of this partnership or do you think that lies ahead?

PJ: I think there’s an awareness. I think King is very careful until Malcolm X’s assassination. King utilizes Malcolm for leverage in the political mainstream. Malcolm X represents for white Americans, including elected officials the alternative to King. So if you think King is too militant, King is too radical. Then you’ve got Malcolm X to deal with, someone who is the boldest critic of white supremacy of his generation. And so I think that Malcolm and King realize what the other is doing for them.

But because King is so mainstream, Malcolm is the person who’s more willing to be seen with King. And that makes sense, right? Because when you think about King, it’s almost like when you think about a corporation that’s too big to fail. Now Malcolm, as we see by 1963, becomes this international figure as well. Starting in 1959 but especially in 1963-64, he’s traveling overseas. He spends 25 weeks in Africa, the Middle East. The famous Oxford Union debate. So he’s really becoming more of a global figure.

But the person who is a global leader, who’s really been given the imprimatur of the world, of mainstream politics, is the Nobel Prize winner. For these reasons, King is less interested in a formal partnership with Malcolm X. And Malcolm would be more interested because King has more to lose. But by the time Malcolm is assassinated and as we see with Watts in a lot of ways what’s going to happen to King, is that he loses his alter ego. Yes. Stokely Carmichael and King. But King loses that Malcolm X figure. And King is going to be forced to become further radicalized. And I argue really, in the later chapters, for the radical King, the revolutionary King.

AC: You talk about these two intertwined but different notions of radical black citizenship and radical black dignity that stand at the center of the book. Can you explain in more detail what you mean?

In this book, you argue for a more expansive understanding of these two remarkable figures. In particular, you talk about rescuing them from the suffocating mythology that surrounds them. I was so struck by was this phrase, how conventional images do no justice to these complex and changing figures. Does this apply equally to both of them or is the mythology more restrictive for Malcolm X or Dr King?

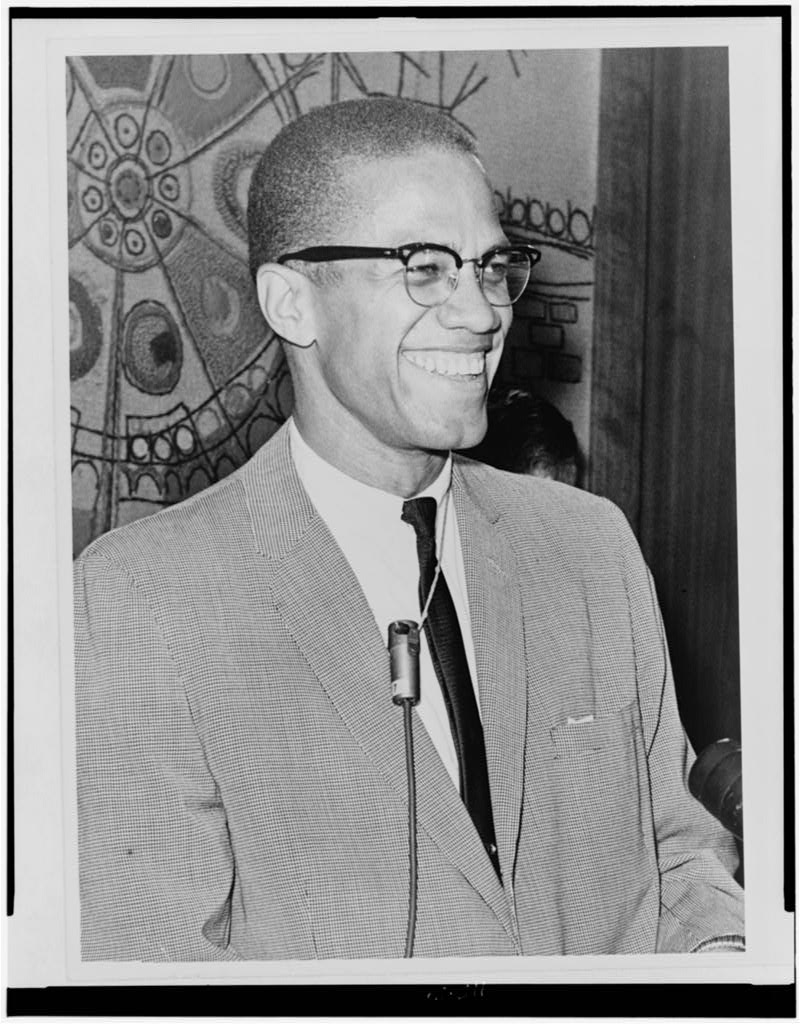

PJ: You know, I think it restricts both of them. So for Malcolm, this idea of being this black warrior really takes away from who he is. We’re not allowed to see the vulnerability, the sense of humor, the fear at times that he has, the shortcomings. Ossie Davis, the late Ossie Davis, an extraordinary actor and activist, has this great eulogy for Malcolm X, saying he was our living Black manhood, our shining Black prince. And there’s positives there, positives to have Malcolm as this kind of role model. But there’s negatives as well when he becomes somebody that’s impenetrable. Any figure, every leader has faults and flaws, man or woman, because they are human beings like the rest of us. So, Malcolm, when we take him out of that mythology, one, we see what a truly extraordinary figure he was. Because, and I say this in the book, Malcolm experiences racial trauma at a very early age. His father is murdered. His mother is institutionalized. His father is murdered by Black Legion white supremacists. He has this wayward youth that he admits in his autobiography, committing crimes, working odd jobs. He’s arrested for crimes he did commit and given a rather harsh sentence and spends 76 months in jail. And then he really becomes this person who is this intellectual, who is this political leader, this deep thinker, and then this great organizer. And so I think when you label Malcolm as just a warrior, you lose something. I think it hurts Black men because of this idea that Black men don’t have the full range of emotions. You know, it hurts you there.

Two. You’re unable to see what a truly, extraordinarily supple mind and diplomat Malcolm is, because he transforms from a prosecuting attorney into a statesman by 64. What’s so interesting is in Europe and the Middle East and Africa – even though Malcolm speaks at Harvard, at Yale – they see that intellect and embrace him more eagerly than Americans. Right. That’s why he’s at Oxford Union. And they see this brilliant man. Even when people disagree. Because the thing about brilliance and ideas, as you know, is that, of course, we’re not going to all agree on everything. The extraordinary nature of ideas is that we can disagree, hopefully civilly. Right? Well, we learn from each other in those disagreements. Right. And so Malcolm speaks at Middle Eastern universities, African universities, European universities. And they’re interested in him not only because he’s a political activist, but because of his brilliant mind. So he suffers in the standard mythology.

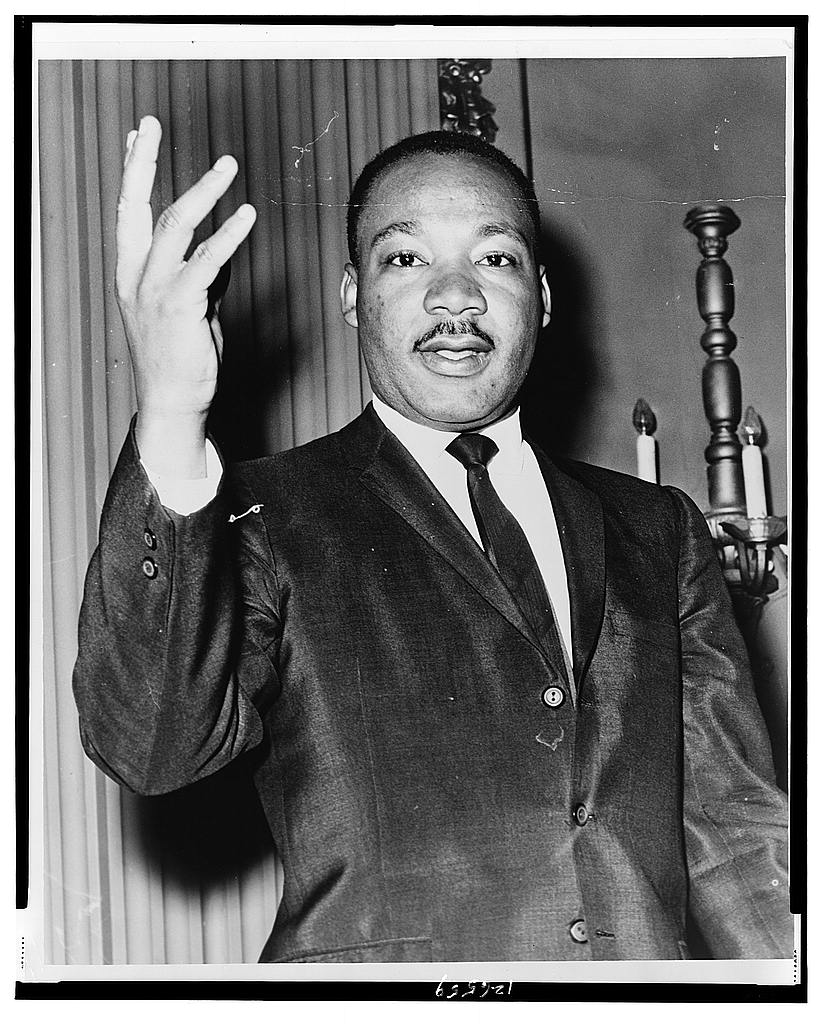

And then King suffers in ways at times on a bigger scale, because King is still a larger, more global figure. When you think about the holiday, when you think about the annual celebrations, when you think about it, King is virtually the only Black American figure accorded this monument in Washington. I mean, you know, we haven’t done that for other Black figures. You know, Harriet Tubman. Sojourner Truth. There’s people that we could pick. Ida B. Wells just won a Pulitzer Prize posthumously from Columbia University for her journalism against lynching in the late 19th, early 20th century. So we have these truly extraordinary figures. But King is the exceptional one. The two most well-known Black figures in American history are King and now Barack Obama. And when we think of King’s suffocating mythology, we don’t want to talk about how much of a revolutionary Dr. King was. We don’t want to say that Dr. King was interested in social democracy, that Dr. King had a criticism against capitalism, that Dr. King remained nonviolent, but the reason Dr. King was assassinated is because Dr. King was using nonviolence to coerce the country into doing things it doesn’t want to do, namely Black citizenship and dignity.

And so King is this anti imperialist, anti-war revolutionary and King becomes a fire breather. What’s so extraordinary is how you can be that radical. And he’s not cursing. He’s not threatening violence. And he’s trying to use the moral force of the witness. Right. John Lewis does the same thing. Congressman John Lewis, when you’re saying you’re going to reveal to the world the opponent you’re up against is using immoral tactics just through your witness. And if the police commit acts of violence, we’re going to roll ourselves up into a ball and let the world watch and the world will decide. Is this the land of the free and the home of the brave? That’s who Martin Luther King Jr becomes.

And the interesting thing about Malcolm and Martin is Malcolm had criticized the march on Washington as the Farce on Washington because he said they didn’t paralyze the city. By 67, 68, as early as 65, Dr. King says that’s the next step. We’re going to use nonviolence to paralyze cities in his essay Beyond Los Angeles. So the two start to have a meeting of the minds. Even though Malcolm is no longer alive by February 21st, 1965. So it’s truly extraordinary.

Part 2 of this conversation with Dr. Peniel Joseph is available here. The banner image comes from Malcolm X and MLK, Jr., mural, E. W. alley view, N. of Manchester Ave. towards Cimarron, Los Angeles, California, 2010. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015647507/

PENIEL JOSEPH holds a joint professorship appointment at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the History Department in the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin. He is also the founding director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. His career focus has been on “Black Power Studies,” which encompasses interdisciplinary fields such as Africana studies, law and society, women’s and ethnic studies, and political science. His newest book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., was published in March 2020 and is available now.

More from Dr. Joseph on Not Even Past

- Stokely Carmichael: A Life

- Muhammad Ali helped make black power into a global brand

- 15 Minute History Episode 90: Stokely Carmichael: A Life

- Watch: “The Confederate Statues at UT”

- The Sword and The Shield – A Conversation with Peniel E. Joseph (Part II)

Consider also reading: