On Monday, July 5, 2021, the high court in Tegucigalpa, Honduras convicted Roberto David Castillo, former head of the Desarrollos Energéticos dam company, for the murder of Berta Cáceres. The court ruled that Castillo coordinated, planned, and financed the assassination of Cáceres.

Speaking in Honduras’ Río Blanco in 2013, Berta Cáceres rallied a sea of supporters against the construction of a new hydroelectric dam. She stressed that the joint economic effort, pursued by China’s state-owned Sinohydro company, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, and Honduras’s Desarrollos Energéticos company, threatened to disrupt countless communities along the Gualcarque River. The project would not only prevent villagers from accessing water for agricultural and traditional medicines, but signaled the plundering of sacred lands. After lambasting the dam, Cáceres briefly paused to ask her supporters if they understood the risks involved in fighting the powerful interests before them. “Are you sure you want to fight this project,” she asked with intensity, “[because] I will fight alongside you until the end, but are you, the community, prepared?” The captivated crowd instantly raised their hands in support of Cáceres and the forthcoming fight against the imperialist venture. Just three years later, however, Cáceres was brutally murdered in her hometown of La Esperanza in western Honduras.

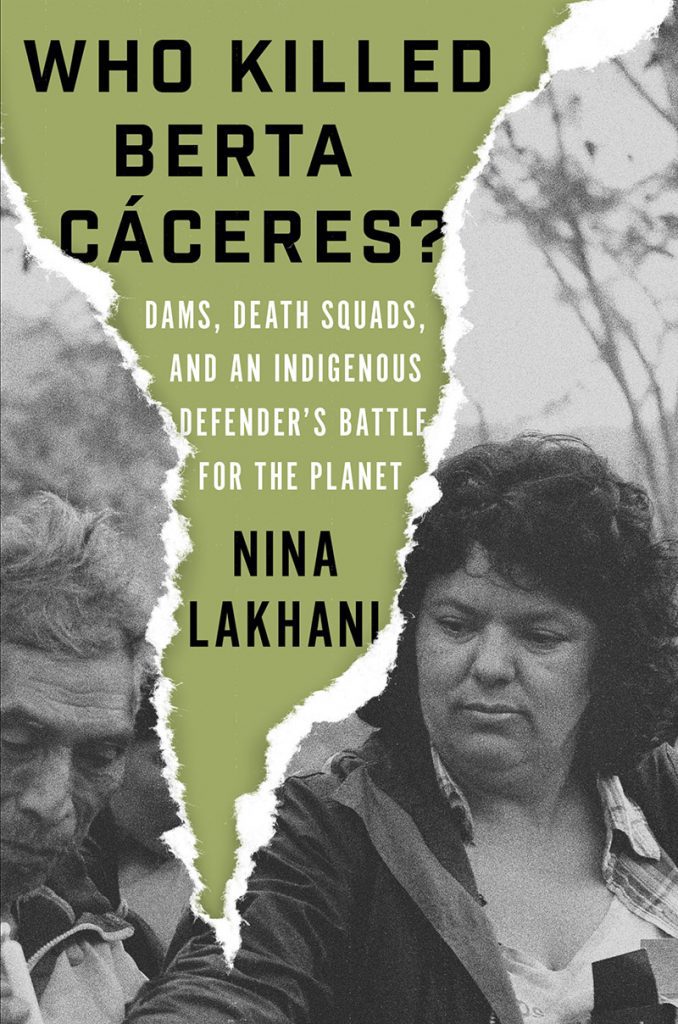

Such vicious violence and steadfast activism is the subject of Nina Lakhani’s captivating new book Who Killed Berta Cáceres?. Drawing on extensive interviews and legal documents, the investigative reporter paints a stunning picture of a woman who refused to let overwhelming bleakness dampen her spirit. Lakhlani begins by spotlighting Cáceres’ service in the “health brigade” of the Salvadoran Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) during the Cold War. During those bloody years, the young Cáceres witnessed the brutality perpetrated by state security forces. These close encounters with death, according to Lakhani, prompted Cáceres to establish a non-violent political organization in 1993 named the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras or COPINH). Over the following decades, the group headed the local communities’ resistance against foreign capital. Indigenous activists staged sit-in demonstrations and set up roadblocks to prevent multinational corporations from extracting from their lands. In Lakhani’s engrossing account, Cáceres stands at the center of this movement, as a leader who for years endured death threats and sexual harassment from defenders of the dam.

Yet Lakhani’s work goes beyond documenting Cáceres’s courageous life and tragic death. The journalist makes considerable efforts to highlight resistance across the broader Honduran population. She gestures to solidarity between Lenca activists like Cáceres and Garifuna leaders like Mariam Miranda in opposition to ecological destruction. Moreover, she highlights how campesino (farmer) organizers like Margarita Murillo relentlessly advocated for the rights of women farmers amidst frequent intimidation from security forces. She then reveals how COPINH members like Juan Galindo and William Rodriguez advocated for environmental justice, eventually giving their lives for the cause. In this way, Lakhani offers a corrective to prevailing media narratives that cast Honduras as a “basket-case,” devoid of significant popular resistance. Like Dana Frank in The Long Honduran Night, she portrays 21st-century Honduras from the activist’s perspective, which affords agency to the people.

Additionally, Lakhani repeatedly reflects on the role of the U.S. in promoting disruptive policies across Central America. She criticizes the Washington Consensus for advocating free-market policies at Honduran communities’ expense. She excoriates former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, in particular, for legitimizing a 2009 military coup that deposed democratically elected President Manuel Zelaya. While Lakhani highlights the violent repression that emerged from the coup’s ashes, she keeps her focus on the activists. She foregrounds Cáceres’ opposition to Clinton who knew “what was going to happen in Honduras” and who authorized the “meddling of North America in our country.” In doing so, the journalist showcases the Lenca activist’s acute awareness of the web of power relations she operated within. Such rich analysis casts Cáceres as a symbol of Honduras: a decent woman caught in a quagmire of self-serving interests.

In essence, Lakhani offers an incisive and impassioned account of the life and death of an incredible activist. Employing meticulous research, including an interview with Cáceres herself, she unveils how Honduran organizers continually fight for their lands in the face of unrelenting threats. She invites readers to recognize the ongoing battle for human rights in Honduras and the human costs of multinational corporations’ plunder. In this way, Lakhani shows that to answer “Who Killed Berta Cáceres?” we must go beyond investigating individual perpetrators. We must also interrogate how corporate quests for profit can corrupt governments and render human life expendable.

You might also like: