by Adam Clulow

Digital Humanities is a capacious term that means different things to different people. For me, Digital Humanities is at its best when it emphasizes “making, connecting, interpreting, and collaborating”.[1] When I did my doctorate, Digital Humanities was just emerging as a set of skills and I paid very little attention to it. I wrote my first book much as a scholar might have done at any point in the past century by diving deep into archives and thinking of a largely academic audience. The key shift came for me when I became stuck as I attempted to write my second book.

My research project at this time focused on the Amboyna (Amboina) conspiracy case, a controversial legal trial that took place on a remote island in Indonesia but involved a global list of characters including Japanese mercenaries, English officials, Dutch merchants, slaves from South Asia and local polities. Because it was so controversial, the case generated thousands of pages of frequently contradictory court records, depositions and other materials. Putting together the different versions of the case creates a dizzying Rashomon- like kaleidoscope of possible interpretations, making reaching any sort of conclusion very difficult.

In 2014, after almost a decade of research on the case, I decided that I had to try something different. My breakthrough came when I noticed that all my students in Australia were talking about a different trial that had taken place some year earlier. What I was witnessing was the remarkable worldwide response to the groundbreaking first season of the podcast Serial, which focused on a 1999 murder case in Baltimore. I watched in wonder as students, who were previously reluctant to engage with legal materials, dissected new pieces of evidence, often devoting hour after hour to the details of a decades-old case. The average Serial episode was downloaded over 3 million times and it generated a tremendous response as the public logged vast numbers of hours working through the key pieces of evidence.

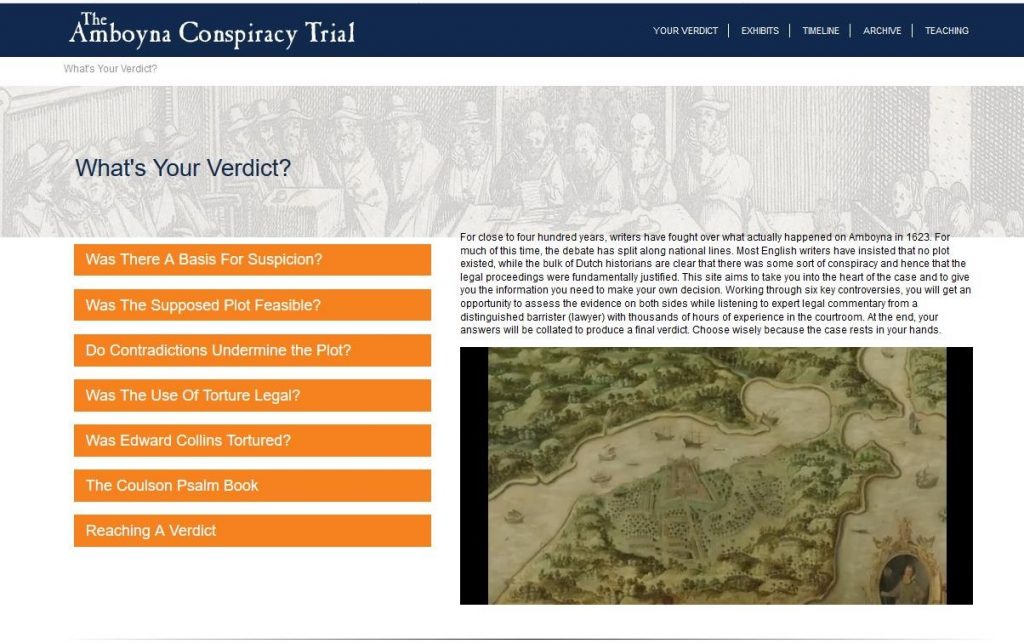

Listening to Serial, I began to wonder if I couldn’t do something similar (on a far smaller scale) for my classroom, that is make a large quantity of information related to the trial I was working on freely available and see if students would respond in the same way by digging into these sources and putting forward their own conclusions. Working with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, I built an interactive website, The Amboyna Conspiracy Trial, designed to do just that. At the heart of the site is an interactive trial engine which places students at the center of the case. To make a complex trial more accessible, we boiled the controversy down to six key questions that have to be answered one way or the other in order to come to a verdict. For each question, the site presents the arguments mobilized by both sides, the prosecution and defense, in conjunction with the most important pieces of evidence, related documents and legal commentary from a distinguished trial attorney. In addition, we created a large repository of additional material and documents, which students can work through at their own pace to support their conclusions.

After hundreds of hours of consultation, design, and construction, the website went live in 2016. It was trialed first with multiple classes at Monash University in Australia, then at Brandeis University and finally at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Students worked through the materials, completed the trial engine, and then arrived at class ready to debate and defend their conclusions. When these tests were complete, we made the website publicly available, and since then thousands of visitors from across the world have worked through it, with their verdicts all recorded in our database.

The site had an immediate impact on students, pulling them deep into complicated material and stimulating impassioned and productive debate in big lecture courses and seminars. Although some students tossed off a verdict after racing through the materials, many others confided to me that they had become engrossed by the details of the trial, trawling through the sources and coming back again and again to key points.

As Digital Humanities tools go the Amboyna website is not especially sophisticated or technologically demanding, but it changed my approach to both the case and the classroom more generally. First, having dozens of pairs of new eyes examining familiar material proved a revelation for me. By homing in on points that I had dismissed too quickly and forcing me to defend lazy assumptions in class, these students helped me think through the mass of evidence. Second, it changed the way I taught. Trying and retrying the case in seminar after seminar was one of the most satisfying experiences of my teaching career and it made me want to incorporate such exercises into all my classrooms. Over the long term, the experience convinced me that I wanted to focus my energies and time on DH resources built for the classroom that could be used to enrich my teaching and then pushed out to other teachers looking for reliable, vetted digital content.

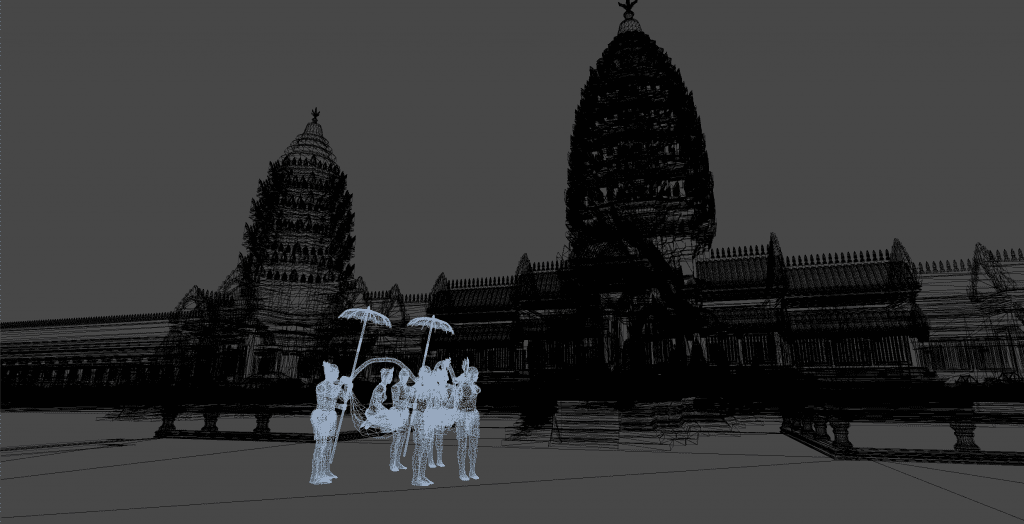

This ethos motivated a second DH project, Virtual Angkor, which was built from the ground up for the classroom. Constructed by a team of Virtual History Specialists, Archaeologists and Historians at Monash University in Melbourne, Flinders University in Adelaide and the University of Texas at Austin across a period of more than ten years, the Virtual Angkor project aims to recreate the sprawling Cambodian metropolis of Angkor at the height of the Khmer Empire’s power and influence around 1300. Although it has been used for research, Virtual Angkor was constructed specifically for the classroom and can be used at both secondary and tertiary level. It deploys advanced Virtual Reality technology, 3D Modeling and Animation to bring a premodern city to life, to place students on its streets and allow them to interact with a historical environment.

Most Asian history survey courses make reference to Angkor but the standard black and white illustrations featured in textbooks make it difficult for students to gain a sense of the scale and grandeur of the city. The Virtual Angkor project allows educators to place students inside the Angkor Wat complex, to view the famous bas-reliefs first hand without leaving their seats, to sail down one of the hundreds of canals crisscrossing the city, to inspect a marketplace selling goods from across Southeast Asia and to watch as thousands of animated people and processions enter, exit, and circulate around the complex. The result is to draw students into a virtual world and then to use this experience as a jumping off point to engage with primary sources.

Both my Amboyna Conspiracy Trial project and Virtual Angkor were driven by faculty, that is by professors like me with an interest in DH and some funding. In 2020, I wanted to try something different: to see if a group of students could develop their own DH resources in the form of historically-based, educationally focused video games. The experiment was driven, first, by an awareness of the dramatic growth of the video games industry in recent years and, second, by a sense that History departments needed to engage more closely with what has become a key conduit for students in our classes.

At current estimates, video games are a $120 billion industry and one that is growing rapidly every year. For university students in particular, video games are pervasive. According to surveys, more than 70% of college students play video games, even more watch gaming content streamed on a range of services and the overwhelming majority report some exposure to video games across multiple platforms. At the same time, video games have become an increasingly important gateway for majors. Many students who enter our classrooms come to History via historically-based games which proliferate across multiple platforms.

Historians can engage with video games in two basic ways. First, we can deploy them much as a film or a novel to interrogate popular understandings of particular topics, moments or figures. Second, we can use them as a learning tool by asking students to design their own games. This was our approach. After an open call for applications followed by interviews, we recruited four students, Ashley Gelato, Michael Rader, Izellah Wang and Alex Aragon, for a semester long Digital Humanities internship focused on game design, story-telling, programming, and history.

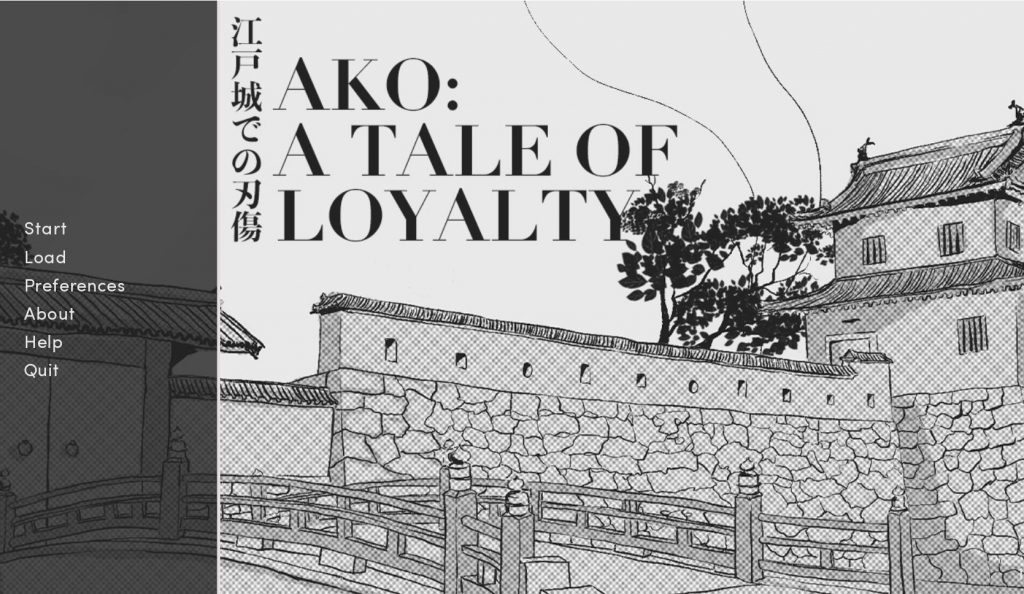

The game to be developed was constrained by a set of guidelines. First, it had to be built around a specific historical episode, the Akō incident (also known as the story of the 47 ronin). Second, the game had to have clear educational payoff that could provide a window into the difficult life of a low-ranking samurai family in the eighteenth century. Third, the game had to be developed on zero budget, using only free, publicly available platforms and software without purchasing game assets.

The result of the experiment was impressive: a deep learning experience for the students, who combined extensive research, multiple disciplines and different technologies, to produce a fully functional game, Ako: A Tale of Loyalty, that was hooked to contemporary scholarship. By the end of the semester in May 2020, the game was distributed to beta-testers who provided feedback. In September 2020, it was used for the first time in a university setting as an educational resource and it will soon be released on commercial platforms where it will be available for download at no charge.

I have other DH projects but the ones described above taught me four key lessons. First, decide what you want to achieve with your DH profile. Having taught at high school and a range of tertiary institutions, I decided I wanted to reach as many teachers and students as possible. For this reason, I built DH resources specifically for the classroom as there is a huge appetite for vetted, scholarly content that is also accessible. Second, the technological hurdle can be as high or as low as you want. Although I have grown accustomed to using bulky Virtual Reality equipment in class, some of my best teaching experiences have been using the Amboyna conspiracy trial website even though this is nothing more sophisticated than a few web pages, some videos and a basic voting system. Third, collaborate always and often. In History, the emphasis is so often on solo-authored publications and this is how we are trained. But DH is done best when you collaborate as widely as possible. This means making connections, working across disciplines, and constantly communicating. For Virtual Angkor, working with Tom Chandler, who teaches in the Faculty of Information Technology at Monash has been illuminating, challenging and always exciting. And fourth, don’t be afraid to share your research. For the Amboyna Conspiracy trial website, I was counseled not to put all my material online as it might be used by other scholars or would diffuse the argument of my eventual book. In fact, sharing these resources was the best thing I could possible have done as it sharpened my argument while creating a community of scholars who pushed me to rethink my assumptions. Although I love working by myself in archives with only the sources and my computer, DH can be an antidote to the sometimes isolating nature of our profession. It pushes us to collaborate, to share and to think about how our research can be useful for others. This is why I find Digital Humanities so exciting and why I think it rewards any time you invest in it.

Right now we are, I believe, in a moment of transition when not only faculty but also undergraduate students can produce world-class DH resources like the Ako game that can be developed across a single semester and then shared around the world for use in a range of classrooms. This makes Digital Humanities skills more important that ever before. All of this brings me to one last lesson that has animated the development of my DH portfolio: Just start. You never have all the skills, all the training and all the resources but you can produce something valuable that will be of use. Whereas academic publishing is measured in months or usually years, DH allows radically different timelines. Starting is often the hardest part of DH projects but in a very short space of time your work can reach a wide audience.

[1] Digital_Humanities. Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp. MIT Press. December 2012.