In 2020-21, the Institute for Historical Studies will convene a series of talks, workshops, and panel discussions centered on the theme “Climate in Context: Historical Precedents and the Unprecedented”. As part of that, we are delighted to publish this roundtable discussion consisting of three reviews focused on Carolyn Merchant’s The Death of Nature, a classic work in environmental history and the history of science. These reviews come out of Dr Megan Raby’s class, History Of Science And The Environment.

- Nature’s Death or the Killing of Nature? Review by Atar David

- A Predecessor to Intersectional Eco-Feminisms Review by Khristián Méndez Aguirre

- Reviving The Death of Nature: Female presences in the configuration of the Early Modern cosmos Review by Rafael David Nieto-Bello

Nature’s Death or the Killing of Nature?

Caroline Merchant’s the Death of Nature (1980) challenges the heritage of progress often associated with the scientific revolution. Forty years since its first appearance, it is more relevant than ever. Rather than blindly accepting the fact that the scientific and intellectual developments of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries fostered progress for all, Merchant asks “progress for who?” as she examines how ideas about nature and scientific innovations brought, in addition to economic and intellectual development, social repression. She suggests an “ecosystem model of historical change,” which “looks at the relationship between the resources associated with a given natural ecosystem… and the human factors affecting its stability or disruption over a historical period” (p. 42-43). For her, nature and culture are deeply connected. Analyzing rich source material, ranging from fiction to scientific writing, Merchant reconstructs the process through which the scientific apparatus recognized alleged problems of disorder with both nature and women, subjugated and regulated the two, and finally institutionalized this intellectual tradition through modern science.

Merchant begins her inquiry by identifying an intellectual tradition that began in ancient Greece, which associated the concept of “nature” with feminine qualities and projected a dual image of both nature and women. On the one hand, the earth was a “nurturing mother” who provided her children – humanity – with products and resources. Such was also the image of the mother/wife who held an important social role in maintaining the household and held key social positions in society. At the same time, nature/woman could be cruel, unpredictable, and chaotic, holding not only the power to build and nourish but to destroy. Some even went as far to present women as witches. Both nature and women posed a challenge for those who aspired to reorganize society according to scientific principles.

Merchant then moves on to describe how both nature and women were subjugated through the intellectual effort and the technological invasions of the scientific revolution. At the core of this revolution stood the idea that nature, which in the past was understood as a holistic organism, was actually a manageable system that can be taken apart and then reorganized to benefit human needs. The idea of a “mechanism,” according to which both nature and the human(feminine) body were seen as machines, allowed a reconfiguration of the two according to scientific as well as economic ideas and interests. The subjugation of nature reached its peak during the seventeenth century with Newton and Leibnitz, whose works helped institutionalize these ideas and created the basis of modern science.

Highly acclaimed for her intervention in both environmental and feminist historiography, Merchant should also be praised for her unique contribution to understanding the power structures that fostered the scientific revolution. Her analysis begins with a Marxist reading of natural changes, where a capitalist struggle over the fenlands, farms, and forests of England (the means of production) resulted in the reconceptualization of “nature”, and later during the seventeenth century, of women as an economic resource. The realization that to maximize revenues and increase surplus value nature needs to be reconstructed and regulated was one of the main catalysts for the scientific revolution. The deterioration in the status of nature and the scientific/capitalist desire to control it was followed by attempts to subjugate women of various social classes. Scientific measures of experiment and regulation were used to control the behavior of lower-class women, while their middle- and upper-class contemporaries were stripped from their production and reproduction of social place and became passive, and therefore dependent on men’s support.

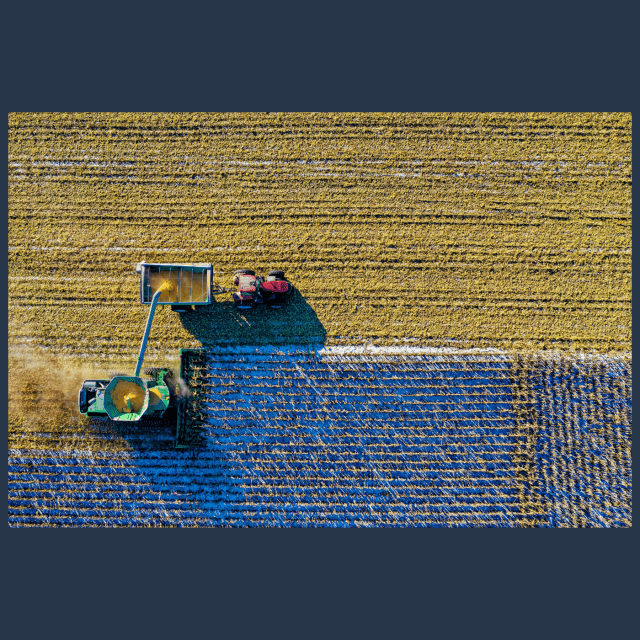

For Merchant, the “death of nature” was not only due to the dramatic ecological changes that followed the scientific revolution, where meadows turned into fields and forests to timber. Nature’s death was first and foremost the result of the collapse of the concept itself. Nature, once a complex ecosystem built on interdependence and equilibrium, became an economic resource, stripped from its core values, turned into a machine in the service of men, a market worthy of man-made regulation. The process described in the book is not so much the “death” of “natural causes”, but rather the killing of it by the hands and minds of men and women who sought to subjugate it, transforming the once vivid system to a passive one. Merchant calls to restore equilibrium to the ecosystem and suggests possible solutions for some of our contemporary ecological and social challenges such as climate change and women’s oppression. The Death of Nature can be read not only as a description of the past, but also as a prescription for a better, more balanced and equal, future.

Atar David is a Ph.D. student in the History department at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on the socio-economic history of the modern middle east, with special emphasis on food, agricultural, and resource allocation.

A Predecessor to Intersectional Eco-Feminisms

Although Carolyn Merchant’s current research is focused on American Environmental history, her first and most influential publication had a much different geographic scope: 16th and 17th-century Europe. The Death of Nature is a text that remains at least as important today as it was following its original publication. Her scholarship explored parallels between women’s movements and ecological movements –both of which sought complementary kinds of liberation in the 1960s. It was also heralded by much more pointed events, like the Three-Mile Island reactor accident in 1979 Harrisburg, PA. More and more, it began to seem like the mastery over nature and women also meant their suffocation and demise. And so Merchant went to work. Her proto-ecofeminist arguments are perhaps even more relevant today, as the backdrop to both environmental activism and scholarship that foregrounds how the impact of environmental degradation is worse for different sectors of the population based on their gender and other forms of identity.

The book details the philosophical, political and economic transitions into modern capitalism and away from a more –to use her term– ‘organic’ understanding of nature. Merchant describes the dissection, control, management, capture and ultimate attempted mastery over nature that also paralleled an equally violent re-conception of women and their control, management, and subjection. Both nature and women, Merchant argues, have become increasingly (but never completely) subjected to man’s mind, his technology, and his theorization of their role in an ideal world. Her examples of violence to the (female) earth and women themselves range from mining to the execution of women accused of witchcraft and the use of forceps to do what men believed midwives could not. Notable men wrote philosophical treaties, supported them with (or used them to justify) capitalist economic systems, and developed physical and conceptual machines and instruments to achieve their progressive mastery over nature and women.

The scope of the book is wide. She foregrounds the role that the environment played in the history of European capitalist societies, like Dutch organic farming and early British technocratic farming during the 16th and 17th centuries. She also identifies the patriarchal philosophical traditions that envisioned organic quasi-egalitarian utopias (like Campanello’s City of the Sun) but also those with sexist and oppressive ones (like Bacon’s New Atlantis). Finally, she situates particular machines, like the clock, in the mechanization of nature. Through wide-ranging sources and methodologies, Merchant firmly establishes her argument within philosophy, environmental history and history of science.

The writing is detailed, but her sections are scaffolded and easy to follow. This makes the text both accessible to a more general audience and worthy of inclusion in any academic study. Some sections contain intriguing and powerful illustrations with historical woodcuts, etchings or drawings. The visual quality of these images provides bold visual references and forceful characterization to her subject: the patriarchal ideas about mastery of nature weren’t only abstractions, but realities experienced by women’s bodies.

As a robust argument for the relationship between the domination of nature and the domination of woman, The Death of Nature paved the way for other kinds of histories of science vis-a-vis particular identities. For example, Merchant’s ‘historicizing ‘the theory of female passivity in reproduction’ during the 16th century, likely influenced –if not all together enabled– the histories that detail the medical experimentation on Black women slaves in the American south during 19th century (such as Deirdre Cooper Owens’ Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and The Origins of American Gynecology (2017)). In summary, the text remains ambitious, rich in sources and approaches, and opened many doors for scholarship to follow its footsteps.

Khristián Méndez Aguirre is a theatre-maker and arts-based researcher, currently a second-year PhD student in Performance as Public Practice in the Department of Theatre and Dance. His research focuses on the relationship between theatrical performance and climate change in the Americas. He holds a B.A. in Human Ecology from College of the Atlantic (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and an MFA in Performance as Public Practice.

Reviving The Death of Nature: Female presences in the configuration of the Early Modern cosmos

Forty years ago, Carolyn Merchant published The Death of Nature which aimed to critically reassess the Scientific Revolution by considering changes in the conceptions of nature in Renaissance Europe. Merchant embraced an ecofeminist perspective, associating images of nature with feminine allegories and metaphors that were popular in intellectual spheres. She linked the consolidation of mercantilist capitalism to environmental transformations and scientific reflections of an expanded canon of thinkers (including women, utopians, and magicians).

She argued that precapitalist nature was understood as a living nurturing feminine organism before the Scientific Revolution, before being gradually transformed into a feminine wild or inert mechanism. That new conception of nature demanded to be controlled and exploited for human benefit and progress. The triumph of mechanism condemned to a secondary role the images of nature, earth, and cosmos as holistic or vital systems, although twentieth-century ecology tended to recover some of those ideas with a certain degree of reductionism.

This book lies halfway between the history of science and environmental history, carefully considering the discourses of thinkers and the concrete processes of land-owning, usage, and exploitation. Because of that, the author analyzed processes of farming, deforestation, famines, fens-drainage. Regarding Francis Bacon, she described how his works illustrate the triumph of mechanism and exploitation of nature, based on the development of crafts and sciences to know and claim power over the female nature. Merchant discovered that the “penetrations” and “inquisitions” of the new Baconian method were related to the language used in witch trials, observing the overlaps in their sexist biases.

The book organizes its narrative and argument around the correspondences between nature and women. Thus, the changes in women’s reproductive and productive roles in a mercantilist world were analogous to the “death” or mechanization of nature. Notable examples of this were the subjugation of early modern women to housework and the end of traditional midwifery. Furthermore, she examined alchemical and philosophical approaches to the conciliation of feminine and masculine aspects of the cosmos and charted the role of female thinkers in the preservation of holistic perspectives of nature. For instance, she studied Margaret Cavendish, a literate and naturalist closely related to the Royal Society of London, and Anne Conway, a cabalist and natural philosopher who was close to Leibniz.

This is a militant book that emphasized the normative condition of the relation between humans and nature. This in no way undercuts the strength and relevance of its purpose. Merchant’s style and arguments were deeply empowered by ecofeminism, and her intentions were not merely descriptive. She was denouncing the moral implications of the transformation in the conceptions of nature and woman in modernity (which were still relevant to her and our time). In a late-Cold War age, she supported an ecological critique of capitalist progress and mechanist sciences from the academic sphere but also engaged as an intellectual in the effort to bring closer the social movements of environmentalism and feminism, very active during the second half of the twentieth century.

Merchant engaged in a context of growing academic criticism toward the technical rationality of modernity, following the legacies of Heidegger and Marcuse. Besides, the influence of the Annales School (a historiographic trend) seems clear when it comes to her effort in connecting geographical and ecological concerns with social history. Additionally, she was committed to Bookchin’s anarchic-communism, shaping her analysis of late-medieval communal peasantry and their organic interactions with nature and also her ideological support to communitarian projects which understand nature as a holistic system rather than as a resource (Mitman, 2006). Nevertheless, she did not advocate for a return to premodern conceptions of nature.

A few critiques can be suggested: she still believed in the existence of a modern Scientific Revolution (Park 2006) and overestimated the agency of intellectual sources to explain concrete environmental changes, instead of focusing on practices. Moreover, the relative omission of the Iberian discovery and conquest of the New World, seems glaring in retrospect (Park 2006). However, her work has brought new opportunities for the scholarship to reframe the relationship between Iberian naturalists and the New World starting from their considerations of nature as wild or profitable.

This book is, despite the latter critiques, a milestone in ecofeminist approaches to the histories of science and the environment. This book should interest readers concerned with natural philosophy, political thought, feminism, and environmentalism. Merchant was important in reframing a predominantly patriarchal history of early modern science and providing a nuanced and source-rich testimony of how gender problems and real women were always present and active in this long story.

Rafael David Nieto-Bello is a first-year Ph.D. student in the History Department. He holds a BA in Political Science and History from the Universidad de Los Andes (Bogota, Colombia). His research interests include the history of social knowledge, Latin America’s intellectual history, ethnohistory, and history of science in the early modern Atlantic. He is currently working on the Relaciones Geográficas’ concern on depicting Spaniards and indigenes’ customs and the configuration of social knowledge to “govern better” the Spanish Atlantic empire.

References

- Mitman, Gregg. 2006. “Where Ecology, Nature, and Politics Meet: reclaiming The Death of Nature.” Isis, no 3 (September): 496-504.

- Owens, Deirdre Cooper. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. University of Georgia Press, 2017.

- Park, Katharine. 2006. “Women, gender, and Utopia: The Death of Nature and the Historiography of Early Modern Science.” Isis, no 3 (September): 487-95.

Image Credit | Image 1: Cover of Death of Nature; Image 2: Photo by Tom Fisk from Pexels; Image 3: Portrait of Francis Bacon via Library Company of Philadelphia.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.