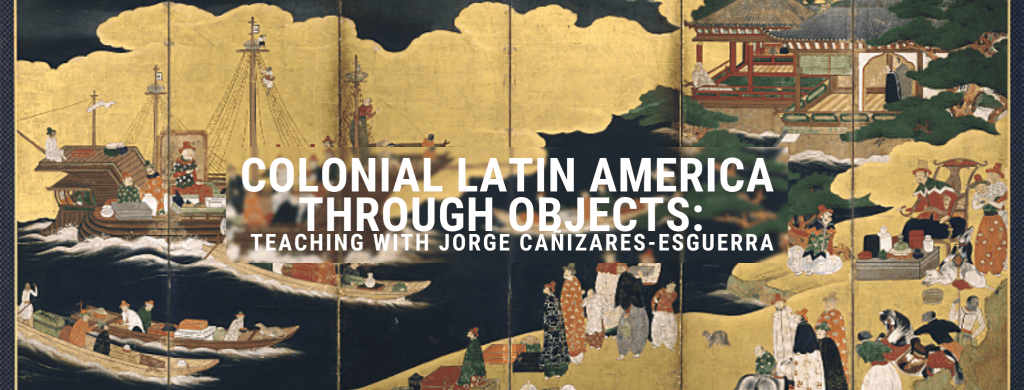

In Spring 2020, Dr Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra taught a new variant of his highly successful course, Colonial Latin America through objects. The course description is as follows:

Objects (furniture, textiles, tools, maps, books, guns, kitchen ware, buildings, settlements, monuments, ships, tombs ) often shed more light about past societies than text themselves. This course explores the past of the colonials Americas (from north to south) by paying attention to the objects these societies left behind. We’ll gain new insights on the history of slavery, education, travel, technology, science, architecture, urbanism in the Americas.

Four students below show how clay ceramics, stones, and screen folds offer significant insights. Two use objects to shed light on the notions of the afterlife among the Mocha and the Aztecs. Another uses a variety of objects the Carib people considered divine, Zemis, to explore indigenous sacralization of space and landscapes. The fourth uses screen folds to explore the way Catholic Japanese communities’ struggled to understand the novelty of Black sailors, translators, and animal handlers present in Portuguese crews.

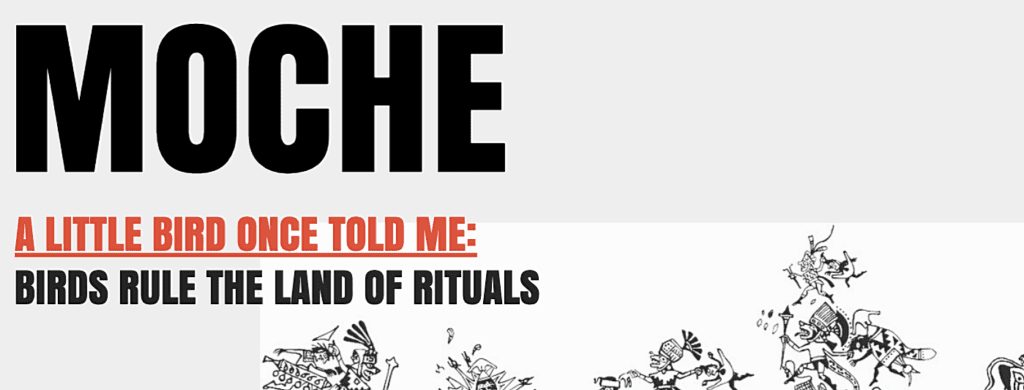

Jeremy Miller

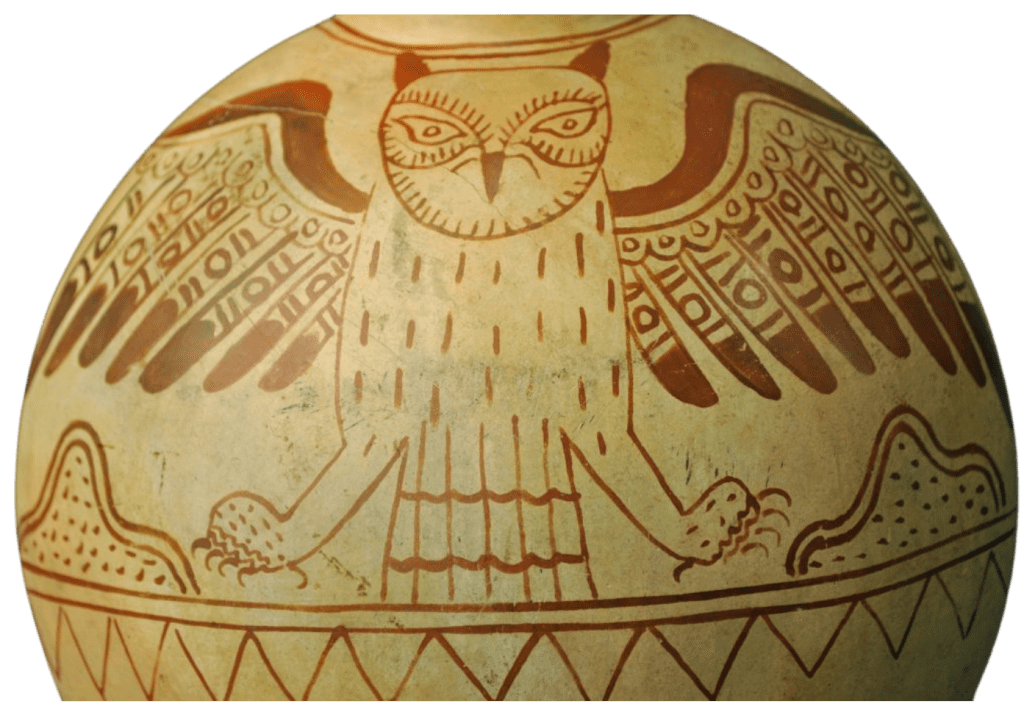

To further understand the complex mythological and religious beliefs of the Moche civilization (AD 1-800), archeologists and historians alike have taken a deep dive into the ancient tombs of this South American tribe to uncover a deep fascination with bird iconography within the ancient civilization. Though a large array of bird species are represented and lay unknown on their meaning to the Moche, it is certain that birds themselves held a high esteem to these peoples as they centered their funerary and sacrificial principles around birds, two instances which were defining characteristics to the culture. Specifically, a careful study of artifacts shows the Moche’s inclined interest between that of the owl, the hummingbird, and the bat, replicating intense meanings within their lingering artifacts and drawings. Though no written record is yet to be found, what can be concluded is that birds played an active role in Moche religion, mythology, and most importantly, in ritual adaptation, making these winged creatures a cornerstone to our understanding of this civilization.

See the full project here…

Ethan Walje

Prior to Spanish contact, The Taino people of the Caribbean possessed a vibrant and diverse culture. Their civilization, however, experienced a significant decline after contact with Christopher Columbus. Without a written record, a great deal of mystery shrouds their beliefs and practices. One window into their culture, however, exists within the Zemi idols that they left behind. By examining the manner in which these idols were created, worshipped, and utilized in Taino society, we are offered a window into the Taino civilization that helps illuminate the relationships that bound their society together. The Zemi idols reveal a society with complex spiritual, societal, and political relationships that are tied together by the worship of Zemis and the creation of the idols that housed them.

See the full project here…

Erika Voight

Prior to the Spanish arrival in Latin America, the Aztecs had long established rituals concerning burials. These practices revolved around ideas of the afterlife and the journeys that it required. In researching the objects special to Aztec rituals, I noticed similarities with Colonial era Catholic beliefs which extended beyond physical rituals, but included beliefs as well. The general afterlife for someone in the Aztec time resembles the Catholic belief in Purgatory and the comparisons between the two vastly different ideologies inevitably leads to a discussion on the primary differences. These differences manifested in various ways once the Spaniards arrived in the “New World”. Oftentimes, the differing beliefs and a need to prove superiority lead to conflict, however some natives welcomed the Spanish with open arms as ancestors. Regardless of the conflict, many Aztec’s held fast to their beliefs and continued to use objects as a way to aid the souls of the dead in their various journeys through the afterlife.

See the full project here…

Abel Martinez

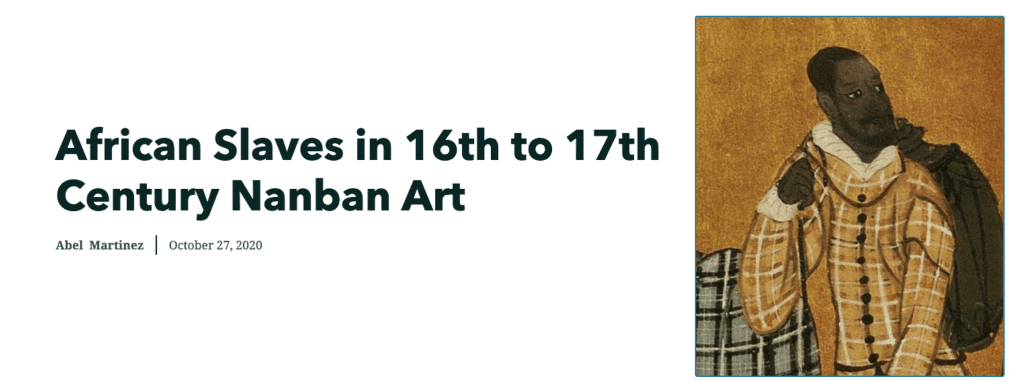

Abstract: This project seeks to understand how Japanese Nanban screen folds helped construct a different narrative of the slave trade in Southern Japan. Black individuals depicted in Nanban art arrived with Portuguese expeditions to Southern Japan as slaves. However, the status of these enslaved Africans was different from those who arrived in the Americas on transatlantic voyages. The African slaves that arrived in Japan often held intellectual occupations (clerics, translators, clerks, guides) and some were proficient in multiple Asian and European languages. These differences were shown in Nanban screen folds that displayed African slaves working alongside Portuguese explorers in many cases rather than as direct subordinates. One central conclusion that should be drawn from this presentation of Nanban screen folds is that although they may have occupied a subservient position in the eyes of the Portuguese, African slaves were, in their own right, explorers of faraway places.

See the full project here…