In his most recent book, Ussama Makdisi provides a more accurate account of sectarianism and coexistence in modern Arab history. In so doing, he repudiates two historical narratives. The first narrative, common in media headlines, claims that sectarian violence is inherent to the religious landscape of the region. The typical counter-argument – the second narrative – describes the region as one of unparalleled toleration, with a history of communal harmony. According to Makdisi, both narratives are politically motivated and false.

Makdisi approaches sectarianism in the modern Arab world by surveying its evolution from the early nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. He calls this period “the age of coexistence.” According to Makdisi, it was less an era of tolerance and harmony but one of persistent struggle for political inclusion. To better comprehend the age of coexistence, he also introduces a new term, the “ecumenical frame,” which he describes as the ongoing political project of valorizing coexistence and opposition to sectarianism. The ecumenical frame refers to three novel formulations: a body of thought that wrestled with secular political equality given the legacy of unequal Ottoman rule, a system of governance with traces of Islamic supremacy, and a legal order that balanced the constitutional secularity of its citizens with religiously segregated law. Makdisi argues that the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries witnessed the emergence of ecumenical thought amongst Arab Christians and Muslims alike.

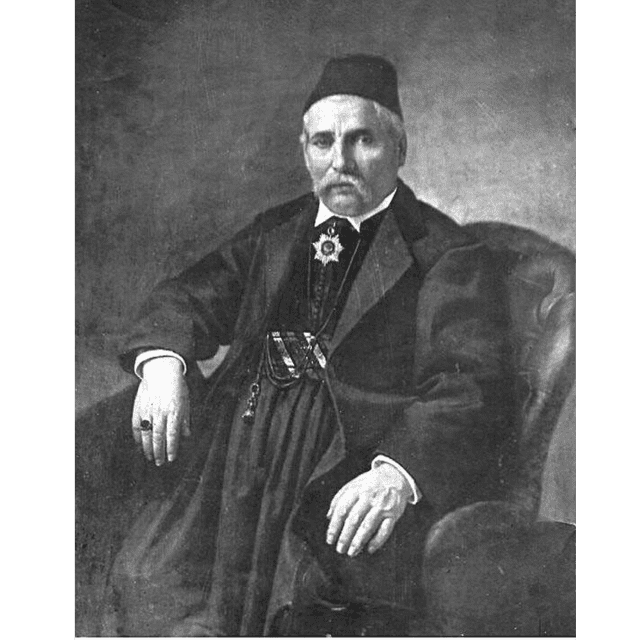

Makdisi breaks the story of coexistence in the modern Arab world into two parts, beginning with its origins during the Ottoman nineteenth century. Opposed to the common narrative highlighting the tolerance of the Ottoman Empire, Makdisi focuses on its inherent contradictions. The empire distributed privileges to religious communities despite upholding the superiority of Muslim over non-Muslim. Ultimately, Ottoman imperial rule favored obedience and loyalty to the sultan, irrespective of religious, ethnic, or linguistic identity. The calculus of Ottoman rule was severely challenged during the mid-nineteenth century by European colonialism and missionary intrusion. The Ottoman government responded by issuing numerous initiatives called the Tanzimat reforms. Makdisi documents episodes of sectarian violence between Muslim and non-Muslim subjects that occurred under the tremendous stress of transition in the Tanzimat Era. He acknowledges the sectarianism of the eastern Mediterranean, culminating in the massacres of 1860, while locating the concurrent origins of the antisectarian ecumenical frame within the writings of nahda (renaissance) intellectuals like Butrus Al-Bustani. Amidst the violence of 1860, Bustani called for transcendence, reconciliation, and ulfa (concord, familiarity), instructing his readership to turn away from sectarian fanaticism and towards patriotism and shared national identity. Makdisi’s familiarity with the Ottoman nineteenth century allows him to pay proper attention to voices like Bustani. He argues with precision and erudition as he presents the violence of 1860, spurring the writings of Bustani, as the crucible of the ecumenical frame.

Makdisi then shifts attention from the Ottoman nineteenth century to European colonialism in the early twentieth century by presenting an innovative comparison between the development of the northern and southern regions of the Ottoman Empire. He first attends to the Ottoman north, the Balkans and Anatolia, where state violence rendered the potential of the ecumenical frame irrelevant. In a poignant example of the amplification of violence, Makdisi shows how in 1821, during the Greek War of Independence, the Ottoman government hung the Greek Orthodox patriarch as a warning for non-Muslim subjects of the empire. One century later, during the destruction of the Christian quarters of Izmir in 1922, Turkish nationalist forces killed the Greek Orthodox Bishop Chrysostomos, allowing the mob to mutilate his body. While the Ottomans sought to bring the Greeks back under their governance, the Turks sought their elimination. According to Makdisi, the draconian practices of the Ottoman (now Turkish) north were not replicated in the Ottoman south, otherwise known as al-Mashriq or Greater Syria, where the ecumenical frame developed between 1860 and 1914. Ottoman subjects in al-Mashriq mutually discouraged sectarianism, viewing it as a problem of ignorance, which culminated in an emphasis on national unity between Muslims and non-Muslims. By bifurcating the Ottoman north and south, claiming a distinct evolution of the ecumenical frame in each, Makdisi generalizes the history of the entire Ottoman Empire. The borderlands between Anatolia and Greater Syria were gradual, not stark. However, Makdisi’s strategic decision to sever the history of Greater Syria from the atrocities of Turkish nationalism in Anatolia extends Arab ecumenism beyond its Ottoman origins.

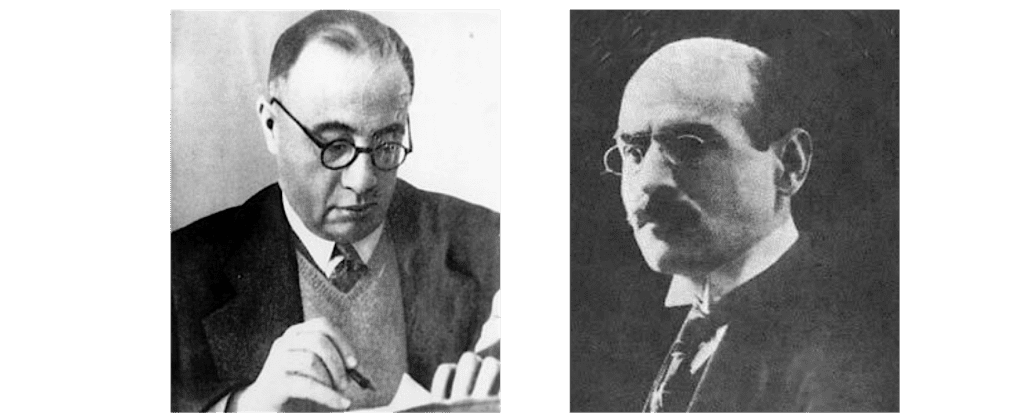

In the second half of the book, Makdisi sketches the development of the ecumenical frame from its Ottoman origins to its politicization within the nascent Arab nation-states. He initially contrasts the manifestations of political ecumenism in Lebanon and Iraq, focusing on the views of Michel Chiha and Sati‘ al-Husri. Chiha, one of the architects of the Lebanese constitution, worked closely with French colonial authority to craft a communalist political culture. Husri, a prominent Arab nationalist thinker in Iraq, advocated alternatively for a secular nationalist culture in opposition to British colonial authority. As Makdisi explains, both political visions, despite their differences, originated in the ecumenism of the late Ottoman Empire. Chiha and Husri sought to overcome sectarianism and political exclusivity in Lebanon and Iraq respectively. Nonetheless, their ecumenical efforts were derailed with the establishment of the state of Israel. While Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq witnessed the logical continuation of the Ottoman ecumenical frame, novel sectarian conflicts between Arabs and Jews altered the trajectory of Palestine. The events leading to the establishment of the Jewish state in 1948 created new ecumenical identities as Palestinian nationalism coalesced under the banner of anti-Zionism rather than religion, class, clan, or geography. Makdisi ends his work with a melancholic yet hopeful tone for the broken but ongoing project of ecumenism in al-Mashriq.

Makdisi excels throughout the book in outlining the logical evolution of the ecumenical frame without choreographing its inevitability. He crafts a powerful and timely response to misrepresentations of the Arab world, which haunt contemporary politics. In doing so, he achieves a rare feat by seamlessly bridging the historiographical divide between the late Ottoman Empire and modern Middle East. Readership within and outside of the academy will find this work useful as Makdisi’s ecumenical frame provides an empathetic and consequential perspective on the making of the modern Arab world.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.