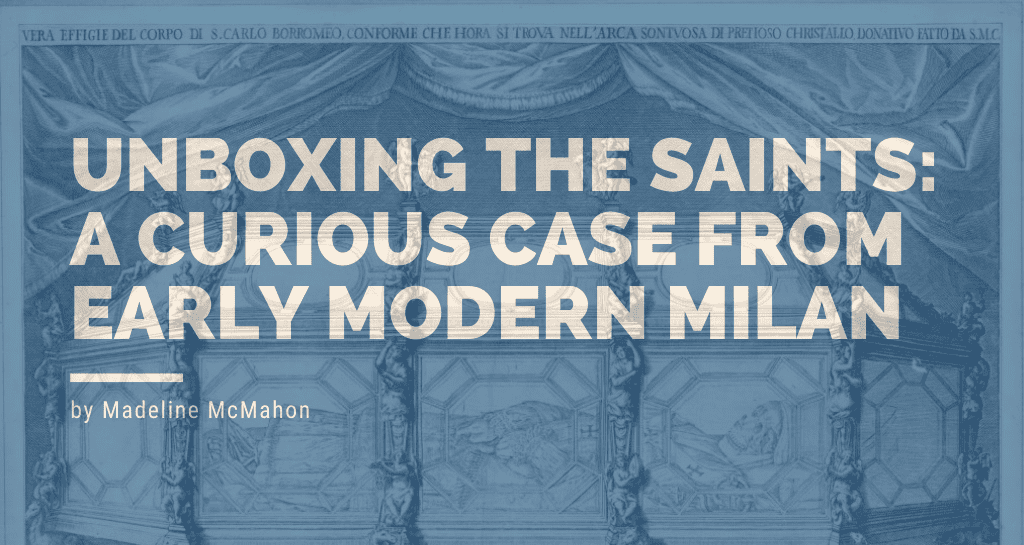

The second half of the sixteenth century witnessed a slow but steady shift in how saints and their remains were authenticated in the Catholic Church. In 1563, in its final session, the Council of Trent affirmed relics’ sanctity and due veneration against Protestant claims to the contrary, but also sought to ensure that relics really were worthy of veneration. Protestants like John Calvin had mocked not only the devotion paid towards religious relics, but also the vast quantities of fake relics in circulation. Trent stipulated, without specifying precisely how, that newly discovered relics had to be acknowledged and approved by the bishop. New practices emerged to ensure the authenticity of holy objects. At the opening of reliquaries and tombs, the local bishop brought witnesses, notaries, and even anatomists in order to detail what was found. This approach was quickly codified in local ecclesiastical legislation.

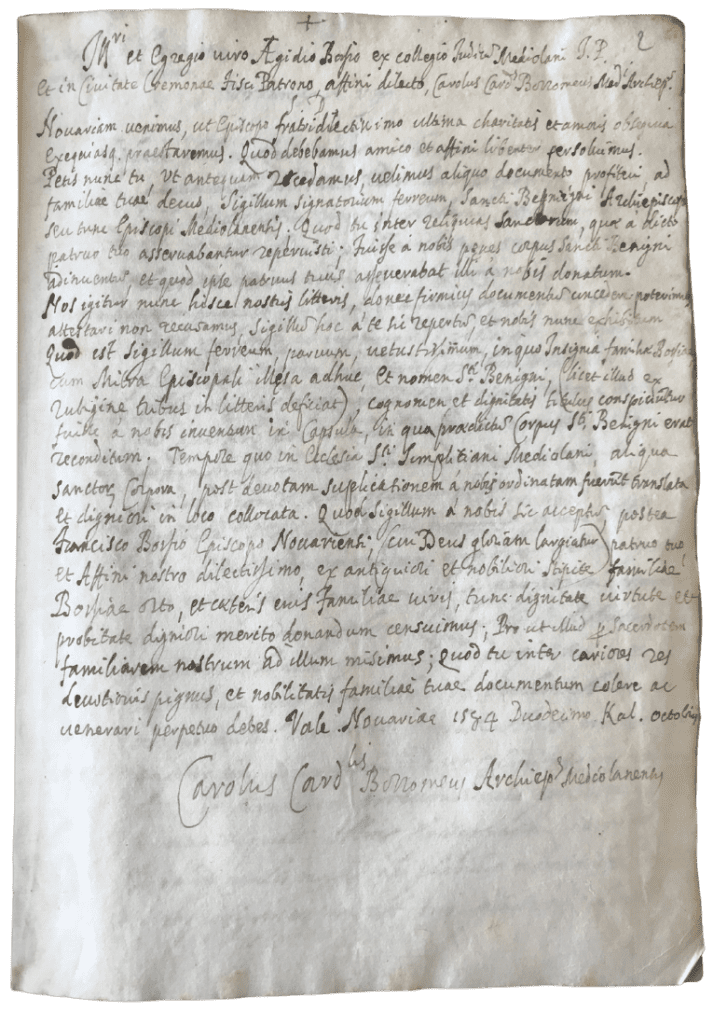

One letter in the Milanese archdiocesan archive (Archivio Storico Diocesano di Milano) seems at first glance to offer a compelling story about how Carlo Borromeo, archbishop of Milan (d. 1584), identified the remains of his late antique predecessor, Milan’s fifth-century archbishop St. Benignus. Borromeo wrote to Egidio Bossi to explain how this ancient saint had been found with the Bossi family’s insignia:

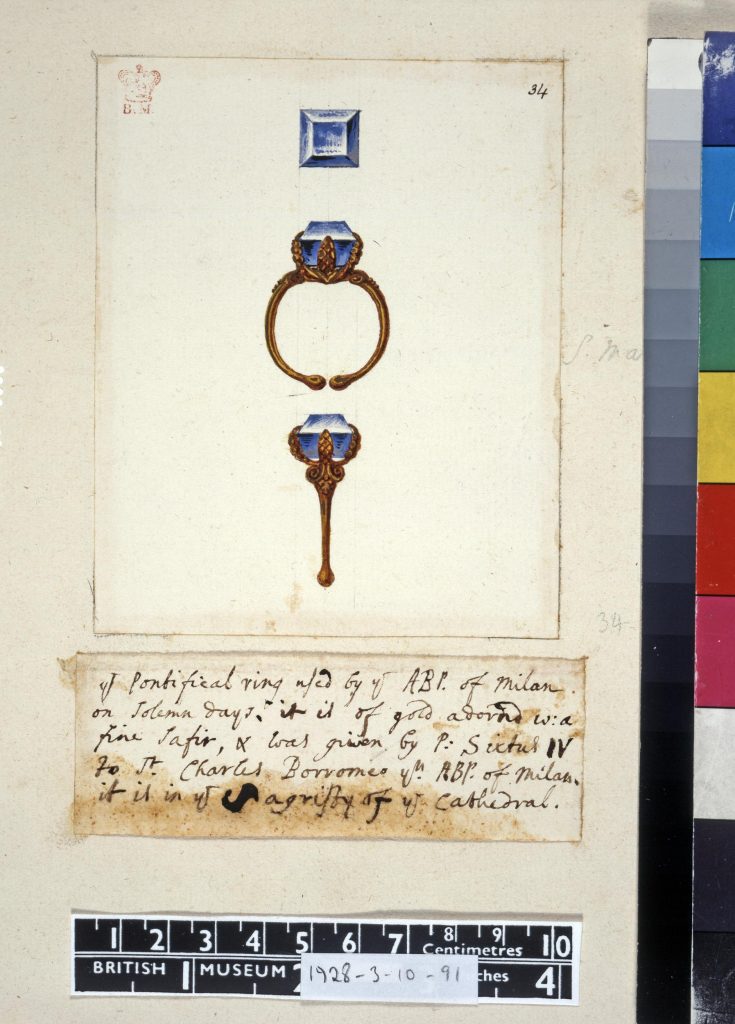

Until we are able to grant firmer documentation, we do not refuse to attest with this letter that this signet ring—which is a small and very old iron signet ring, with the insignia of the Bossi family and the episcopal miter still whole, and the name of St. Benignus (although three letters are missing due to rust)— … was found by us in a box in which the aforesaid body of St. Benignus was found. At which time, in the church of San Simpliciano in Milan, some bodies of holy saints … were translated and gathered into a more dignified place.[1]

The ring itself, according to the letter, had been given to Egidio’s late uncle, Francesco Bossi, the bishop of Novara. Borromeo urged Egidio to take care of his uncle’s ancient ring “as a document of the nobility of your family.”

When I first came upon this letter, I was thrilled. Here was Borromeo, Indiana Jones-like, hacking into a bishop’s tomb and emerging with a powerful ring, just legible enough to tie this long-dead saint to one of northern Italy’s leading families. I wondered how the ring had been described in the formal finding, or cataloguing, of the saint’s bones. Had those present immediately recognized the coat of arms of the Bossi? I had read a manuscript copy of this catalogue in a different library, so I returned to my notes. According to that record, Borromeo had opened the box with St. Benignus’ bones in 1581 and found “a few pieces of congealed blood” and nothing else.[2] Where was the iron ring? This description suddenly cast the letter in a different, and suspicious, light: it was in Latin, a language Borromeo rarely used in correspondence with his fellow Italians, and it was nestled among documents from the 1620s and 30s, not the 1580s.

Benignus “Bossi’s” signet ring was a fake: a later forgery created as part of a feud between Milan’s aristocratic Bossi and Benzi families. The ring had been produced in the early seventeenth century, decades after Borromeo’s actual encounter with St. Benignus in 1581 and Borromeo’s death in 1584. In 1617, in a formal judgment in Rome, this ring provided apparently ironclad evidence for the Bossi’s claim that St. Benignus was an ancestor of theirs. They alleged that the ring had been found in the formal opening of the saint’s tomb by Borromeo—who had just recently been canonized as a saint in 1610. As an eighteenth-century historian, Angelo Fumagalli, pointed out, this feud was one of several attempts in seventeenth-century Milan to make specious genealogical claims on the city’s earliest archbishop saints. Just as the Borri and Albigatti had skirmished over St. Monas, and the Beverate and Soresina over St. Simplician, so the Benzi and Bossi both asserted their kinship with St. Benignus.

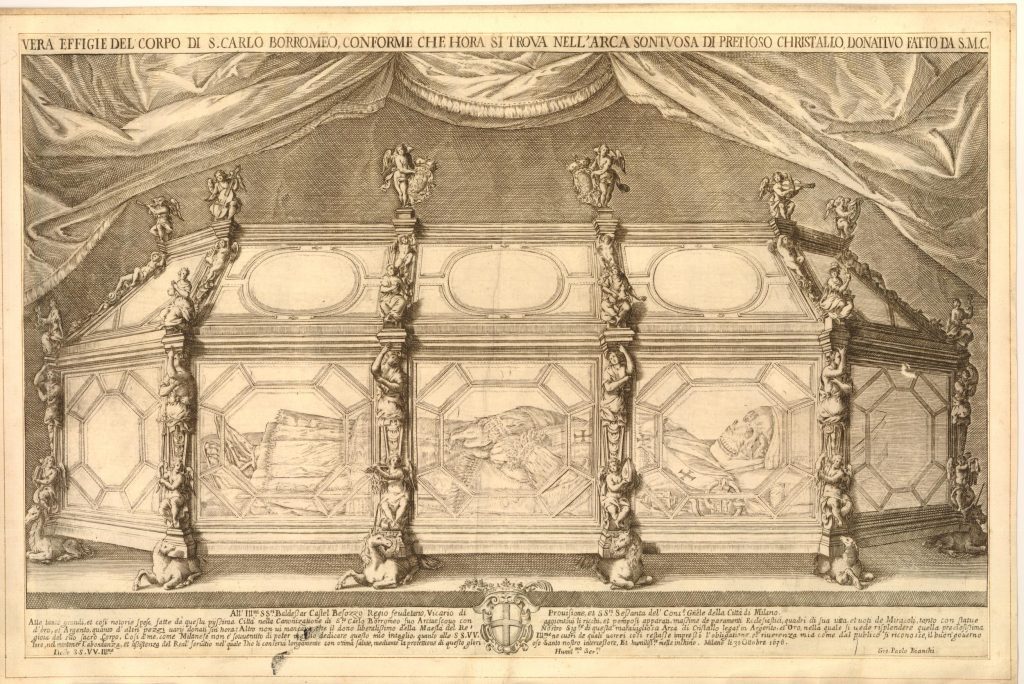

The letter in the Milanese archive was forged—either around the same time as or perhaps after the 1617 judgment— to provide a believable context for the fake ring. I had been looking for documents about how Carlo Borromeo interacted with relics in the sixteenth century. But I found this seventeenth-century forgery useful nonetheless, because it illuminated Borromeo’s legacy in shaping the sacred landscape in Milan. Borromeo had legislated the proper process for authenticating and preserving relics quite carefully, with greater specificity than the general Council of Trent. Relics were to be described in order, and diligently written down, along with any further information from monuments or inscriptions. The seventeenth-century creators of the fake ring and accompanying letter clearly knew that an object like a saint’s ring found in the tomb would have been written about, as part of the relevant information gleaned from the saint’s surroundings. They also knew that Borromeo had translated (ritually processed and reburied) the bodies of St. Benignus and other early bishop saints buried in the Milanese church of San Simpliciano. Perhaps there was still a collective memory of this event, refreshed thanks to the ceremonies and printed biographies that celebrated Borromeo’s canonization in 1610. In some ways, the Bossi’s later efforts to coopt a fifth-century archbishop of Milan show how successful Borromeo was in making the city’s past archbishops and their relics an integral part of Milanese life. These kinds of families wanted to be associated with the saints whom Borromeo had honored.

And yet, ironically, the claims of the Bossi and other prominent families suggest that Borromeo’s reforms of the city failed in important respects. Borromeo sought to remove prominent and ornate individual tombs from Milan’s churches. He removed the sarcophagi of Milanese dukes hanging on chains from the ceiling of the Duomo, so that they would not compete visually with the main altar. In this period, bishops like Borromeo also worked to remove family-funded chapels from the perimeter of churches, and the family coats of arms that often decorated individual tombs as well as private chapels.

Decades later, the Bossi family found a creative workaround. By imagining that Borromeo had once found their family crest inside St. Benignus’s tomb, they effectively made the tomb of the saint into a family tomb, and even suggested that their coat of arms had been found inside that holy space. They used their knowledge of the regulations governing how evidence for relics was documented to then turn these on their head. The same protocol for unboxing the saints that was meant to provide a failsafe—careful documentation by bishops about the inscriptions and imagery found with saints’ remains— instead provided a how-to for successfully passing off a forgery. The Bossi had played by Borromeo’s rules, to a degree. And in so doing, they showed that there was greater continuity before and after the reformer’s episcopate than he would have liked. After all, family crests and the tombs of the nobility were still found in churches, and fake or misidentified relics still proliferated. But the forged letter and fake ring also show that denizens of seventeenth-century Milan had mastered the ways of looking at and documenting relics that Borromeo and the Council of Trent had introduced—enough, even to counterfeit them.

Madeline McMahon is a post-doctoral fellow in history at UT Austin. You can find her on Twitter @madmcmahon.

______

[1] The letter, in Archivio Storico Diocesano di Milano VII A 25, fasc. 1, fol. 2r, is reprinted in Aristide Sala, Documenti circa la vita e le gesta di San Carlo Borromeo, vol. 3, vol. 3 (Milano: Ditta Boniardi-Pogliani di Ermenegildo Besozzi, 1861), 555, https://books.google.com/books?id=t1AYAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=egidio%20bossi&f=false

[2] Biblioteca del Seminario Arcivescovile di Bologna, MS Oppizzoni 4901, fol. 7v.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Bradford Bouley, Pious Postmortems: Anatomy, Sanctity, and the Catholic Church in Early Modern Europe (2017) -For more on how bodies, in particular, were examined in order to make cases for sainthood in the Counter-Reformation Church.

- Anthony Grafton, Forgers and Critics (1990) -A modern classic illuminating the productive interplay between those who create forgeries and those who expose them.

- Katrina Olds, Forging the Past: Invented Histories in Counter-Reformation Spain (2015 – Olds shows how the pressures of the Counter-Reformation led one enterprising Jesuit to forge, wholesale, an invented past for Catholic Spain.

- Ingrid Rowland, The Scarith of Scornello: A Tale of Renaissance Forgery (2004 – How a 17th-century Italian teenager forged a cache of ancient Etruscan documents and objects and had to live with the consequences.

________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.