This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

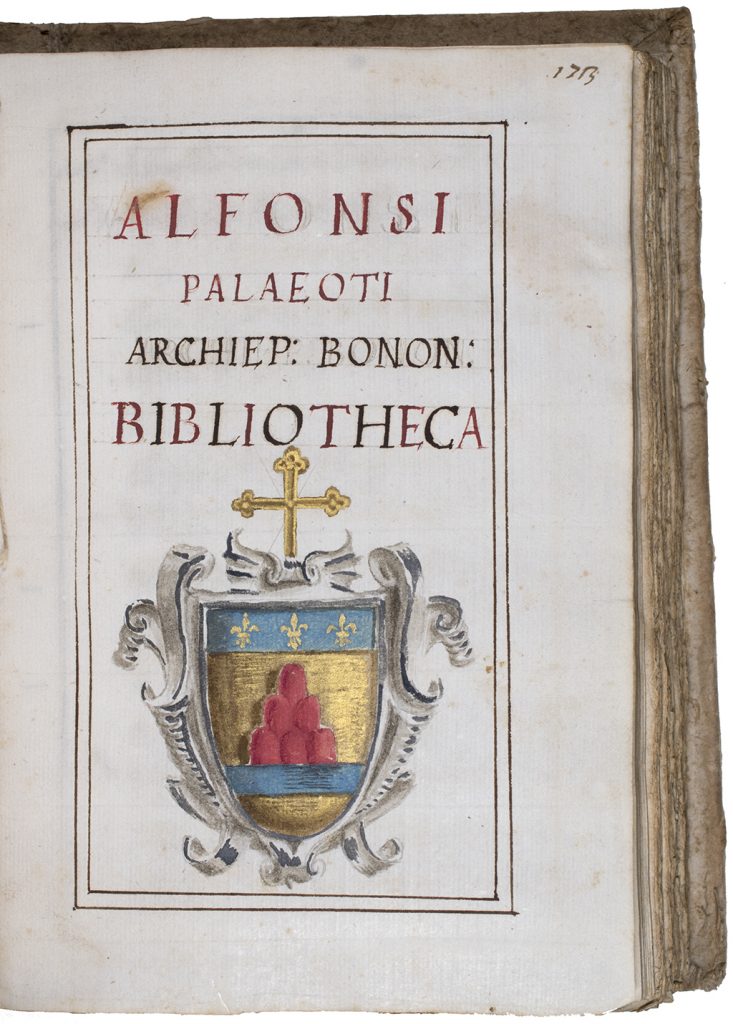

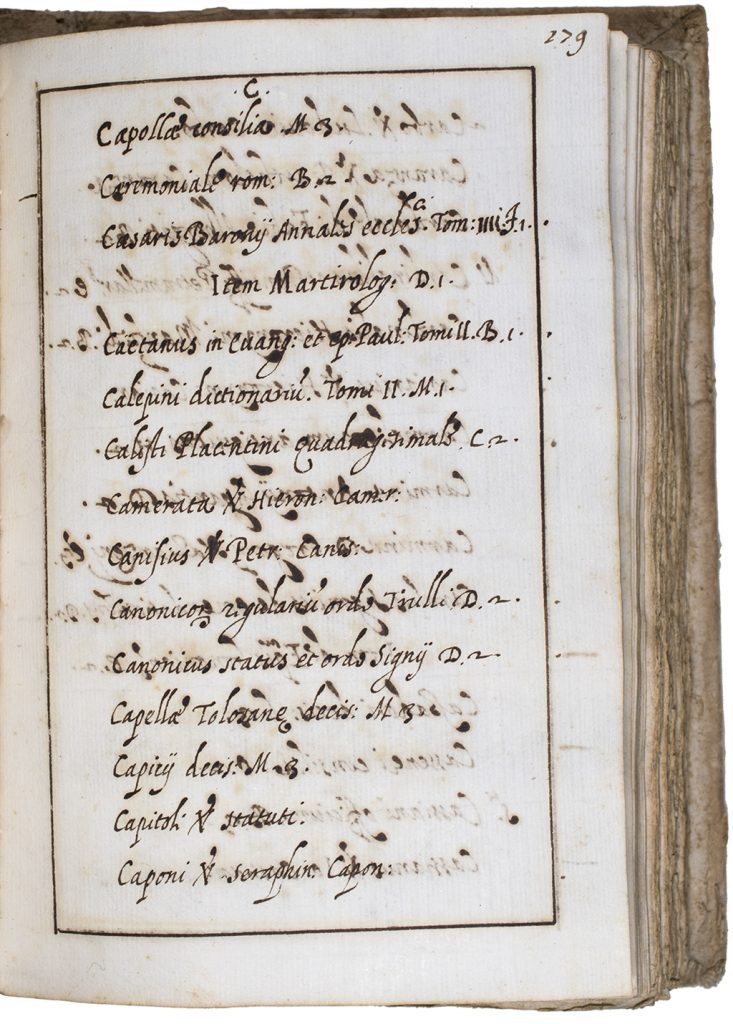

The library catalog of Alfonso Paleotti, the archbishop of Bologna from 1597 until his death in 1619, begins with a flashy title-page bearing Paleotti’s illuminated coat of arms, and, written carefully in red and black ink, the words, “The Library of Alfonso Paleotti, Archbishop of Bologna.” Judging from the long list of books that follows, Paleotti’s collection contained much of what we might expect to find in an archbishop’s library in the early seventeenth century. There were works on religious history, including Baronio’s Annales ecclesiastici, a gargantuan work on the history of the Catholic Church, published in several volumes between 1588 and 1607.1 He owned the Bible and writings by the early church fathers, like St. Ambrose, too. The catalog even included Paleotti’s own bestseller about the shroud of Turin, an object that mystified and fascinated early modern visitors much as it does those in the 21st century.2

The shelfmarks entered next to many of the archbishop’s books in the catalog hint at the less straightforward story of how Alfonso’s library came to be. They show us that the books were largely inherited from his predecessor in office, his cousin Gabriele Paleotti, archbishop of Bologna from 1567 to 1597. A comparison between a 1586 catalog of Gabriele’s library with the Ransom Center catalog of Alfonso’s reveals that many of the books in Alfonso’s library retained the same shelfmarks they had in Gabriele’s collection.3 For example, a 1578 martyrology by Pietro Galesini under the shelfmark E.2 in Gabriele’s catalog was also listed as E.2 in Alfonso’s.4 And although added by a later hand in Gabriele’s catalog, Baronio’s Annales was kept under F.1 in both.5 As in Alfonso’s, Gabriele’s catalog generally lists books alphabetically by author, with a shelfmark at the end of the entry.6 Even the title-pages of the two archbishops’ catalogs are similar, featuring their shared family crest. But not everything is identical. In addition to adding more recent books like his work on the shroud, Alfonso also removed books that had been included Gabriele’s catalog and could no longer be found. It seems Alfonso had done due diligence: missing books were marked as such in Gabriele’s catalog by a later hand, and a list was compiled of the hundreds of missing books.7 Alfonso’s catalog in the Ransom Center lists the books that survived.

The many missing books perhaps attest to the collection’s heavy use. Gabriele wanted his books to serve as a kind of public library for clergy, particularly poor clerics who could not afford to buy good books to help them write sermons. During Gabriele’s lifetime, the English Catholic refugee and theologian William Shepreve served as librarian for the archbishop’s collection, “always adding books, not only for the service of the archiepiscopal palace, but also for preachers, or others who have need of the books, of which he keeps an index.”8 In his final years, Gabriele took steps to make his personal book collection a permanent feature of Bologna’s archiepiscopal palace. He had a purpose-built room constructed for it in 1595, and in his will, he stipulated that a complete inventory be drawn up within two months after his death, and that no book be sold or taken out of the library.9 The catalog in the Ransom Center advertises itself as “the library of Alfonso Paleotti.” In reality, though, Alfonso’s library was both a family heirloom and an institutional resource for the archdiocese of Bologna.

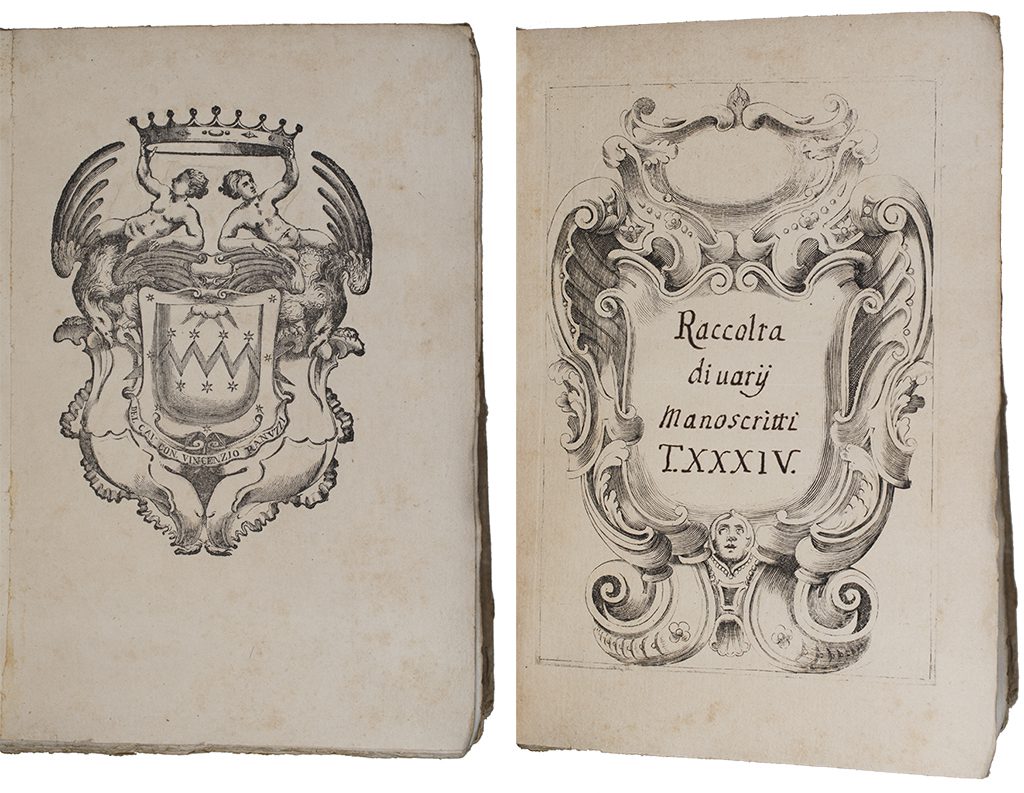

The current location of Alfonso’s catalog is also revealing. It is bound as part of a miscellany of manuscript material (both originals and copies) from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This single volume is one of the 620 volumes the Ransom Center owns from the Ranuzzi collection—another Bolognese family library. This collection was started by Count Vincenzo Antonio Ranuzzi, between 1706 and 1726, who wanted to preserve information and knowledge for his son, Marc’Antonio.10 As in other Ranuzzi volumes, the one containing Alfonso’s catalog begins with Count Ranuzzi’s own elaborate coat of arms and a title-page with a shelfmark. This one was the 34th volume in the library’s “Raccolta di varii manoscritti,” or “collection of various manuscripts.”

It seems likely that the Ranuzzi acquired Alfonso’s catalog during the Count’s initial burst of collecting in the first decades of the eighteenth century; by 1731, another archbishop of Bologna had searched for this text in vain. Better known as Pope Benedict XIV, Prospero Lambertini was archbishop of Bologna from 1731 to 1754 and made it his pet project to restore the Paleotti library in the archiepiscopal palace to its former grandeur. Lambertini lamented that in 1642, Archbishop Girolamo Colonna had moved the collection to a different and more spacious location: “But in that part [of the archiepiscopal palace], nobody remembered it.”11 During one of Bologna’s wet winters, the books became water damaged. Lambertini had the books repaired, including the magnificent Antwerp Polyglot Bible that he had found “mutilated,” and moved them to another wing. He also sought to fulfil the stipulation in Gabriele Paleotti’s will that an inventory of the books be made by his successor. He wrote, “With no amount of diligence could we find this catalog—if it was ever made.” So, in 1738, Lambertini created a new catalog. And he had it printed so it would avoid the same fate as the manuscript catalog Alfonso must have made:

We had this inventory of the books that could be found printed so that there would be many copies, and it would never again disappear, if it were only left copied in manuscript—as we strongly suspect happened earlier to the first catalog, which we don’t doubt was created and compiled by Alfonso Paleotti, who succeeded Gabriele, even if as we said, it never came into our hands.12

If only Lambertini had thought to send his agents on a short walk across town to Palazzo Ranuzzi, where Alfonso’s missing catalog was already bound and shelved as “Raccolta di varii manoscritti,” Vol. 34.

Fortunately for us, the once-elusive manuscript is now in Austin. In addition to solving a little eighteenth-century puzzle about its existence and whereabouts, its presence at the Ransom Center makes it possible to tell part of a long history of the creation, continuation, and destruction of book collections in Bologna. The vast majority of the sources we study as historians are often several times removed from their original contexts, and recovering those contexts often requires tracing the sinuous provenance of the books and manuscripts that preserve them. We can see other places that Alfonso’s catalog had meaning when we learn that it moved to Ranuzzi’s collection and was sought after by Lambertini in the eighteenth century.

A similarly rich story could be told about the catalog’s journey to Texas. What does Paleotti’s catalog tells us about the movement of books in early modern Bologna? The libraries of elite families and ecclesiastical institutions overlapped, and, even though both were intended to preserve knowledge for future generations, books often went missing. The creation of one library drew on the dissemination of books from others. Gabriele’s creation of an archiepiscopal library incorporated his own family’s books.13 Books that had once been kept in the Palazzo Paleotti were moved to the Palazzo Arcivescovile. Even then, under Alfonso’s care, the collection continued to blur the line between a personal library and a public, institutionalized resource. And as Alfonso marked books in Gabriele’s old catalog as missing, more almost certainly disappeared. A century later, the Ranuzzi turned to Bologna’s ecclesiastical libraries as well as the city’s private collectors to create their family library, making their collection out of the remnants of many Bolognese libraries. The catalog documenting “The Library of Alfonso Paleotti, Archbishop of Bologna” sheds light on one of them.

Madeline McMahon is a PhD candidate in history at Princeton University, funded by the Mellon-CES Dissertation Completion Fellowship (’20-’21). Beginning in the 2021–2022 academic year, she will commence a postdoctoral appointment in History at The University of Texas at Austin. You can find her on Twitter @madmcmahon.

1 Harry Ransom Center, Ranuzzi Family Manuscripts, Ph 12840, “Alfonsi Palaeoti Archiep: Bonon: Bibliotheca,” fol. 175r, and “Annales ecclesiastici Baronii Tomi III. F 1,” fol. 179r.

2 Ranuzzi Family Manuscripts, Ph 12840, fol. 174v. “Alfonsus Palaeatus Dichiaratione della sindone.” Alfonso Paleotti, Esplicatione del sacro lenzuolo (Bologna: Heirs of Giovanni Rossi, 1599).

3 Biblioteca comunale dell’Archiginnasio, MS B. 1348, “Catalogus bibliothecae…Gabrielis Palaeoti.”

4 Pietro Galesini, Martyrologium S. Romanae Ecclesiae (Venice, 1578). Ranuzzi Family Manuscripts, Ph 12840, fol. 198v. Archiginnasio, MS B. 1348, fol. [137r].

5 Ranuzzi Family Manuscripts, Ph 12840, fol. 179r. “Caesaris Baronij Annales eccles.ci Tom: IIII F.1.” Archiginnasio, MS B. 1348, fol. [31r]. “Cesaris Baronii Annales ecclesiastici Tom. 4. F.1.”

6 In fact, Alfonso’s catalog tended to list works both by title and author’s first name, while Gabriele’s listed works under author’s first name.

7 Archivio Arcivescovile di Bologna, Misc. v. 841, fascicolo 7, “Index librorum qui in archiepiscopali bibliotheca desiderantur.”

8 Quoted in Paolo Prodi, Il cardinale Gabriele Paleotti (1522 – 1597) (Rome, 1959-1967), vol. 2, 264-65. “sempre si va aumentando di libri, non solo per servitio dell’Arcivescovato ma ancora per predicatori, o altri che habbino bisogno de libri, de quali tiene l’indice.”

9 Prodi, vol. 2, 266-67.

10 Maria Xenia Zevelechi Wells, The Ranuzzi Manuscripts (Austin, 1980), 1–5.

11 Prospero Lambertini, Catalogus librorum qui reliqui inventi sunt in bibliotheca archiepiscopali Bononiae (1738), sig. a 2 v. “Primo adventu nostro Bibliothecam Cardinalis Palaeoti, studio Cardinalis Columnae novis Codicibus ornatam deprehendimus in amplo quidem loco Sedis Archiepiscopalis, sed in ea parte ubi nemo commoratur. Quare ob negligentiam hominum factum est, ut per hyemis tempora in eum locum aquae penetraverint.”

12 Lambertini, Catalogus, sig. [a 3v]. “Porro hunc Catalogum (si fortasse antea confectus est) nulla diligentia potuimus invenire: Illum modo Librorum, qui inventi sunt, Typis imprimendum committimus, ut multa exemplaria suppetant, ac ne rursus intereat, si solum manu descriptus relinquatur, uti contigisse merito suspicamur primo, quem ab Alphonso Palaeoto (qui Cardinali Gabrieli Palaeoto statim successit) confectum, digestumque minime dubitamus, licet in manus nostras, uti dictum est, nunquam pervenerit.”

13 Prodi, Il Cardinale Gabriele Paleotti, vol. 1 (1959), 52-53, vol. 2 (1967), 264.