By Susan Deans-Smith (Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin) and John W. Smith (Independent Scholar, University Affiliate Research Fellow-Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies)

This article is the second of two parts in a series entitled, Hidden in Plain Sight: Reflections On A Mexican Baroque Enigma. You can read the first part here.

One issue that continually surfaced during our research focused on the unresolved question and confusion about the authorship, date, and content of Miranda’s extant portrait. To repeat ourselves in order to be very clear, the extant portrait is undated, signed “Miranda fecit,” and contains only one inscription, Sor Juana’s biography. Octavio Paz lamented that “The fact that critics insist on saying that it was painted in 1713 indicates that they are repeating secondhand information without having seen the painting” (1988, 236). Almost thirty-five years later, the confusion continues. We decided that if we could find definitive evidence of the existence of a second portrait that is dated 1713 with two inscriptions that would at least resolve one issue: yes, Miranda painted two portraits of Sor Juana, one undated, signed, with one inscription, and the other signed, dated 1713, with two inscriptions. Untethered from a questionable date of 1713 offers different possibilities for the date of the extant portrait and its commission and creation. The presence of Sor Juana’s three published volumes in the portrait based on the third volume’s publication in 1700 as well as Siguenza’s death in 1700, however, also narrows possible dates. Given the portrait’s commemorative purpose, the commission could have been made as early as 1698/99 in anticipation of both the anniversary of her death and Fama’s publication. Beginning in 1697, the wealthy Mexican priest and journalist Juan Ignacio de Castorena y Ursúa Goyeneche y Villarreal (1668-1733) oversaw the compilation of Sor Juana’s works based on writings that he had collected and taken to Spain with him. He solicited tributes from both Spanish and Mexican contributors to be published in Fama, that included Sigüenza. As such, knowledge about the intended publication preceded 1700.

The most compelling evidence for the existence of two portraits of Sor Juana by Miranda appears in the work of Aureliano Tapia Méndez (1993, 1995) and Rogelio Ruiz Gomar (2004). We reread this evidence to see if we had overlooked important information related to a second, now missing, portrait. As it happens, we had, which in turn led us to focus on looking for photographs of it. Before we address their arguments, a brief review of the foundational literature on Miranda’s portraits helps to better understand the sources of confusion about the portraits as well as their “lives.”

The first notice of a portrait of Sor Juana, signed by “Miranda” and dated 1713 appeared in an essay in the Mexican periodical El Renacimiento (1894) focused on known portraits of Sor Juana including those owned by the nuns of San Jerónimo. The author, the Mexican writer and historian Luis González Obregón (1865-1938) formed part of a group of Spanish and Mexican writers and scholars engaged in research into both the visual and textual sources of Sor Juana’s life and works in the late nineteenth century to rescue her from the oblivion of two centuries. Indeed, González Obregón wrote the essay in anticipation of commemorations of the bicentenary of her death in 1895, which much to his dismay never materialized. González Obregón’s description, however, was purely textual with no illustration of the portrait included, and only a note that it belonged to one of the nuns of San Jerónimo. The description, moreover, came not first-hand from González Obregón but from his friend and colleague, José María de Ágreda y Sánchez (1838-1916), sub-director of the Biblioteca Nacional, librarian at the Museo Nacional, and of the Biblioteca Pública de la Catedral Metropolitana. Ágreda y Sánchez’s connections resulted in permission for him to view a portrait by Miranda of Sor Juana in the possession of the nuns of San Jerónimo and from which – at González Obregón’s request –he transcribed its two inscriptions and the text of the sonnet that appears on Sor Juana’s desk. González Obregón published the full texts of those transcriptions: Sor Juana’s biographical inscription, her sonnet, Verde embeleso, and a second short inscription that refers to the portrait’s commission by Sister María Gertrudis de Santa Eustaquio.

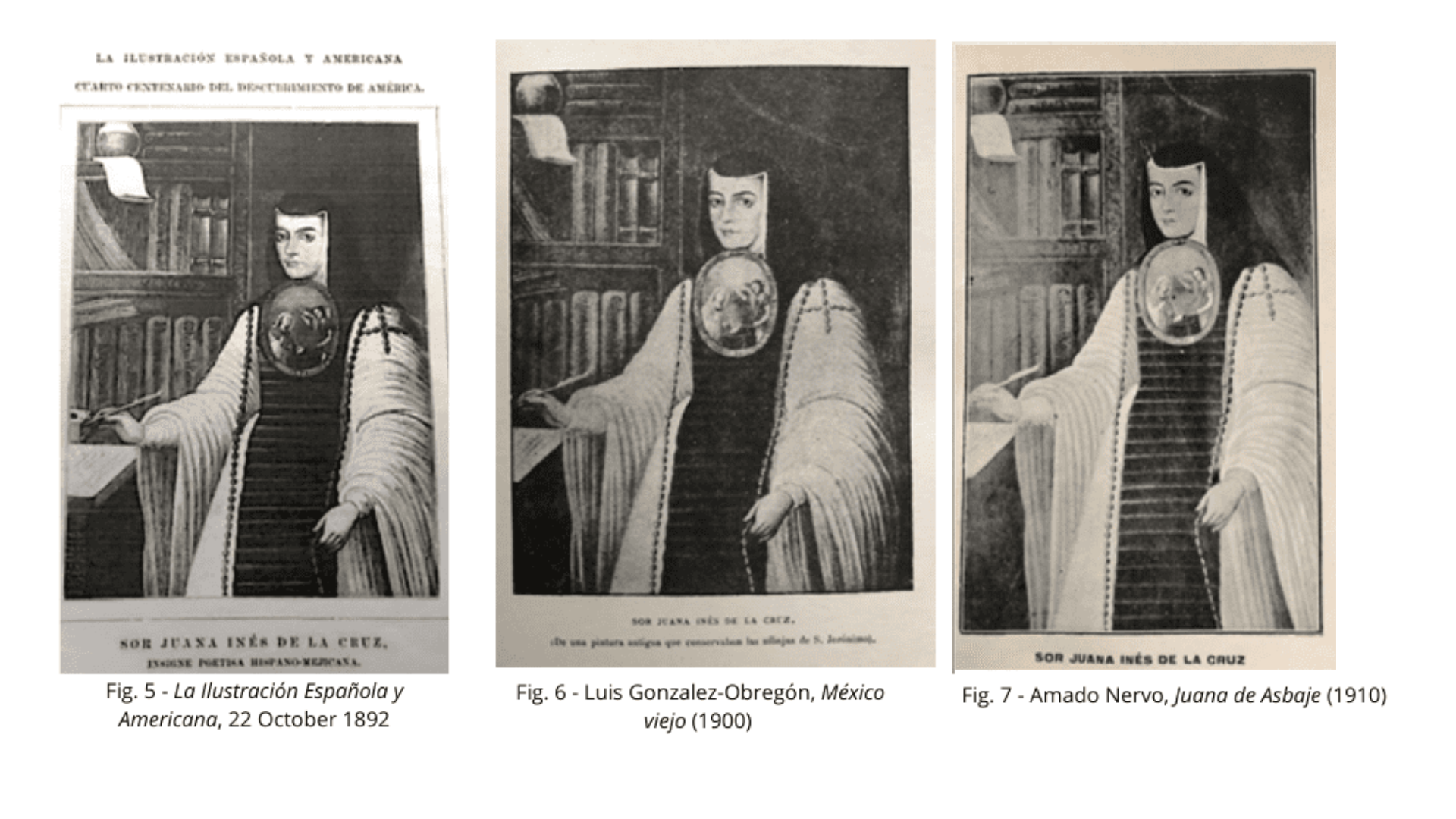

González Obregón provided no actual description of the portrait’s composition by Miranda so other than information about the two inscriptions, sonnet, date and artist, readers had no idea what it looked like. He did, however, include a brief description of a portrait of Sor Juana owned by a nun of San Jerónimo (but did not reproduce the actual image) that appeared in Madrid in La Ilustración Española y Americana (1892) (fig. 5) that describes her standing in a library at her writing table having just completed writing something. The cropped portrait is, in fact, by Miranda but was not identified as such. So, this is one of the first insights that we had not realized before: by the 1890s there was: a) textual evidence of a portrait by Miranda dated 1713 with two inscriptions but no sense of what it looked like; and b) images were starting to be reproduced of the very same portrait but not recognized as such, presumably because of the heavy cropping that eliminated the inscriptions.

In an expanded version of the essay he published in El Renacimiento, González Obregón subsequently included an image (fig. 6) in Mexico viejo (1900) very similar to the one published in La Ilustración Española y Americana. The journalist-diplomat-writer, Amado Nervo (1870-1919) would reproduce the same image used by González Obregón in his Juana de Asbaje (1910) (fig. 7). Again, the fact that the portraits are cropped such that there is only a hint of an inscription on the side of Sor Juana’s writing table and no second inscription may account for why writers did not identify it as Miranda’s portrait as described by González Obregón. Rather, the captions for the illustrations simply identify Sor Juana and/or provide a variant of “From an old painting kept by the nuns of San Jerónimo.”

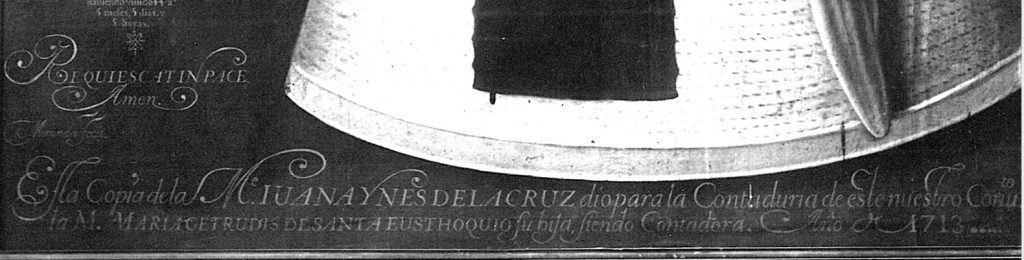

Two subsequent publications contributed to additional information about Miranda’s portrait dated 1713 and with two inscriptions. In 1899, Vicente de P. Andrade (1844-1915) included in his Ensayo bibliográfico mexicano del siglo XVII the text of Sor Juana’s biographical inscription that appears in Miranda’s portrait with a note that indicated that it was copied from the painting preserved by the nuns of San Jerónimo. He also included the text of another second short inscription that differs from the one Ágreda y Sánchez copied and reads “Copy of the sonnet that Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz gave for the Accounting Office of this our convent to Mother María Gertrudis de Santa Eustaquio, her [spiritual] daughter and Accountant. Year of 1713—Miranda fecit.” The full text of the sonnet is included. It is unclear whether Andrade drew on González Obregón’s 1894 essay or if he was also able to personally view possibly another portrait by Miranda owned by the nuns but we cannot verify this. An alternative explanation is that he provided a very confused rendition of the second short inscription provided by Ágreda y Sánchez but the differences are such that that is unlikely. Ezequiel A. Chávez’s study of Sor Juana (1931) included a short chapter on portraits of Sor Juana (largely based on González Obregón and Ágreda y Sánchez). He refers briefly to Miranda’s portrait primarily to note that the acclaimed eighteenth-century painter Miguel Cabrera ((1695–1768) documented in the inscription in his portrait of Sor Juana that he copied from it in 1750 where it hung in the Accounting Office of the convent of San Jerónimo. What is distinctive in Chávez’s study, however, is that in a chronology of Sor Juana’s life and works, he includes an entry for 1713 that states that Sister María Gertrudis de Santa Eustaquio gifted Miranda’s portrait of Sor Juana to the convent of San Jerónimo. Instead of reproducing the text of the second inscription published by González Obregón, he transforms its information into a chronological “fact.”

The most comprehensive assessment of the portraits and iconography of Sor Juana after that of González Obregón appeared in 1934 by Ermilo Abreu Gomez (1894-1971), Iconografía de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Following González Obregón closely he lists a portrait attributed to Miranda as “painted in 1713 that was in the possession of the nuns of San Jerónimo,” (21). In his entry for a “portrait in the possession of a Heronymite nun” (22) he cites the anonymous cropped portrait published in La Ilustración (fig. 5). He notes its inclusion by González Obregón and Nervo, and reproduces the image from González Obregón’s Mexico viejo but still no connection is made to Miranda. He also comments on the differences between the texts of the second short inscriptions provided by Ágreda y Sánchez (gift of portrait of Sor Juana by Sister María Gertrudis) and by Andrade (gift of sonnet from Sor Juana to Sister María Gertrudis).

To sum up, what this review of information about Miranda’s portrait of Sor Juana between the late 1890s and 1930s clarified is: 1) reproductions of Miranda’s portrait (cropped) began to appear in publications in both Spain and Mexico as early as 1892. Those images are not, however, attributed to Miranda but captioned as some variant of “from an old painting owned by the nuns of San Jerónimo; 2) descriptions of a portrait that name Miranda specifically as the artist are purely textual based on the original transcriptions of the portrait’s inscriptions provided by González Obregón and Ágreda y Sánchez; 3) aside from the nuns of San Jerónimo it appears that the only other person to have viewed the portrait was Ágreda y Sánchez (possibly Andrade, but that is not at all clear); 4) reproductions of the portrait, whether published in Mexico or Europe would have required a photograph or detailed sketch on which to base them. Given Ágreda y Sánchez’s positions at the Biblioteca Nacional and the Museo Nacional, he may have been responsible for securing a photographer but this remains an open question; 5) none of the works discussed indicated knowledge about another portrait by Miranda with only one inscription, signed by the artist, but not dated.

In 1944, however, Jesús Flores Aguirre (1904-1961), literary scholar, writer, poet, and diplomat, published a short essay on “Un retrato de Sor Juana” in Papel de poesía and Vanguardia accompanied by an uncropped full length black and white photograph of Miranda’s portrait of Sor Juana (fig. 8). He identified the portrait as from a private collection owned by his friend, the scholar, writer, and poet, Gustavo Espinosa Mireles Rodríguez (1917-2009), and gave a detailed description of the portrait including its dimensions, its somewhat deteriorated state, the fact that it is signed by Miranda and although not dated “is prior to 1713.” He also included the full text of the biographical inscription that takes up the entire side of Sor Juana’s writing table as well as that of the sonnet. Subsequently, the portrait was exhibited for the first time in the Exposición bibliográfica e Iconográfica de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz in 1951 on loan from Espinosa Mireles as part of the expansive tricentenary celebrations of Sor Juana’s (alleged) birth in 1651. Espinosa Mireles eventually gifted it to UNAM where it currently resides. But is this portrait the same one that Ágreda y Sánchez saw and those reproduced by González Obregon, Nervo, and Abreu Gomez? No, it is not. It is not dated and it does not bear a second inscription and this is where we return to the studies of Tapia Méndez and Ruiz Gomar that support the argument that Miranda painted two portraits of Sor Juana.

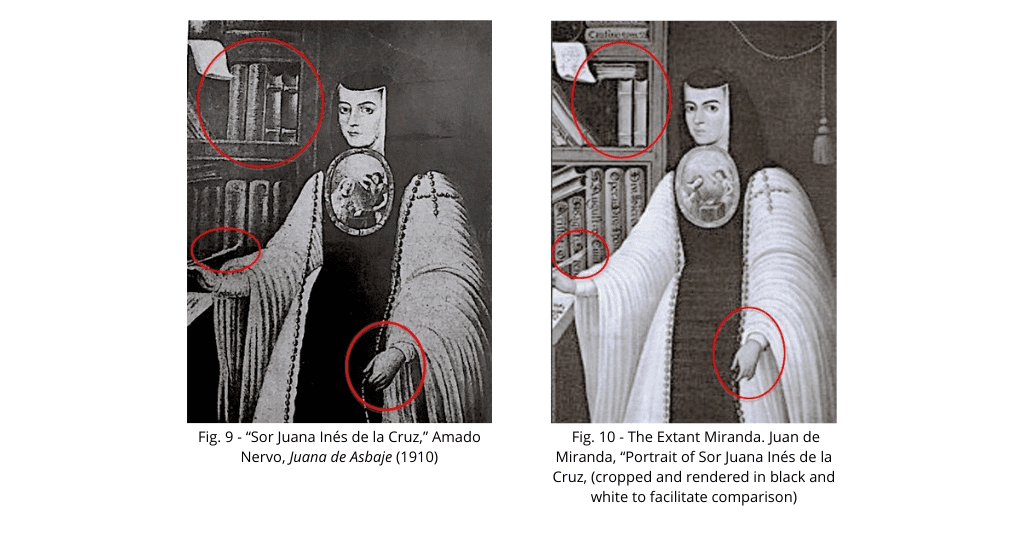

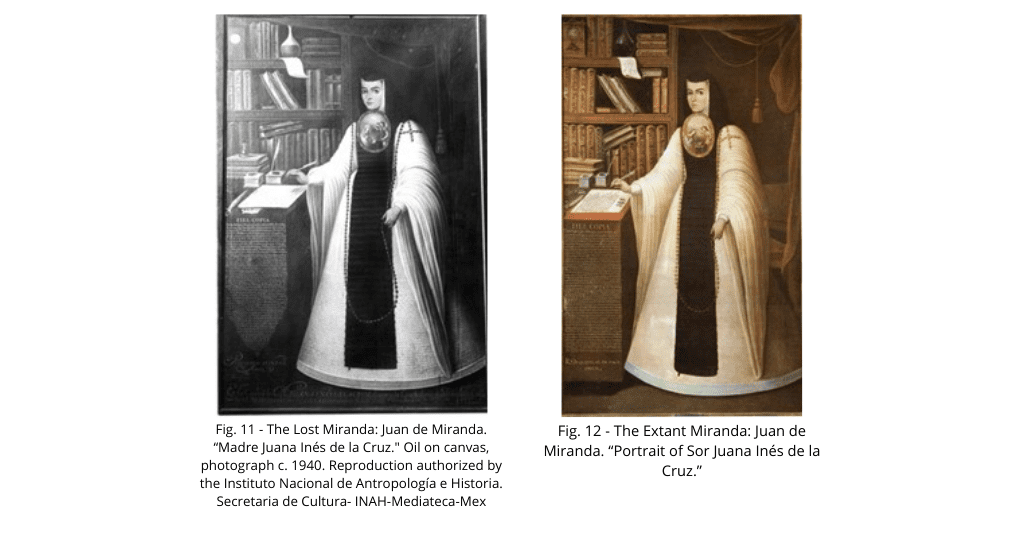

Tapia Méndez concluded that all three images published in La Ilustración Española y Americana and by Gonzaléz Obregón and Nervo (figs. 5, 6, 7), are all the same portrait but not the same as the extant Miranda housed in the UNAM Rectoría. When compared, differences are quite obvious. He emphasizes the arrangement, angles, and sizes of the books on the middle and bottom shelves on the far righthand side of the bookshelf, and the positions of Sor Juana’s hands and fingers, holding a quill in one, and her rosary in the other (figs. 9 and 10).

The legibility of the biographical inscription in the extant portrait also allowed comparison with the one transcribed by Ágreda y Sánchez. Ruiz Gomar observes that although some differences could be attributed to sloppy transcription and/or “alterations during a faulty restoration,” other differences are more significant. He notes, for example, that Ágreda y Sánchez’s transcription reads “Sor Juana took her vows in the church “of Saint Jerome, N[uestro] P[adre], in this Convent” [authors’ emphasis]; the inscription in the extant portrait reads “of Saint Jerome in the Convent.” Another telling difference is that “the phrase, ‘the role of Accountant of this our convent’ in Ágreda y Sánchez’s transcription, appears in the extant portrait as “the role of Accountant in the aforesaid Convent.” Such subtle differences signal on the one hand, specific location: “in this Convent,” as well as of possession: “of this our convent,” in comparison with language that suggests a more formal distanced “aforesaid convent” (2004, 297).

Inspired by these analyses and without any substantive evidence of the whereabouts of an actual physical second portrait to go on, we opted to search for photographs of it. We speculated that may have involved Ágreda y Sánchez, especially given his position at the Museo Nacional. That in turn led us to the extraordinary digital repository developed by Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mediateca and its photographic collections. Finding the photographs of the lost Miranda actually proved to be relatively easy, as long as you know what to look for – in this case, the books’ different arrangements on the bookshelf (figs. 9 and 10). A search pulls up black and white photographs of both the missing and the extant portraits so without looking specifically for that kind of detail it would be very easy to assume that you are looking at the same portrait while scrolling through thumbnails since the portraits are very similar overall. There are two photographs of the missing portrait, one dated c.1915 and one dated c.1940, which are very similar to the cropped versions. With two uncropped portraits now to compare, additional differences become apparent between the extant and missing portraits (figs. 11 and 12). In addition to those detailed by Tapia Méndez, we add the following examples (not exhaustive).

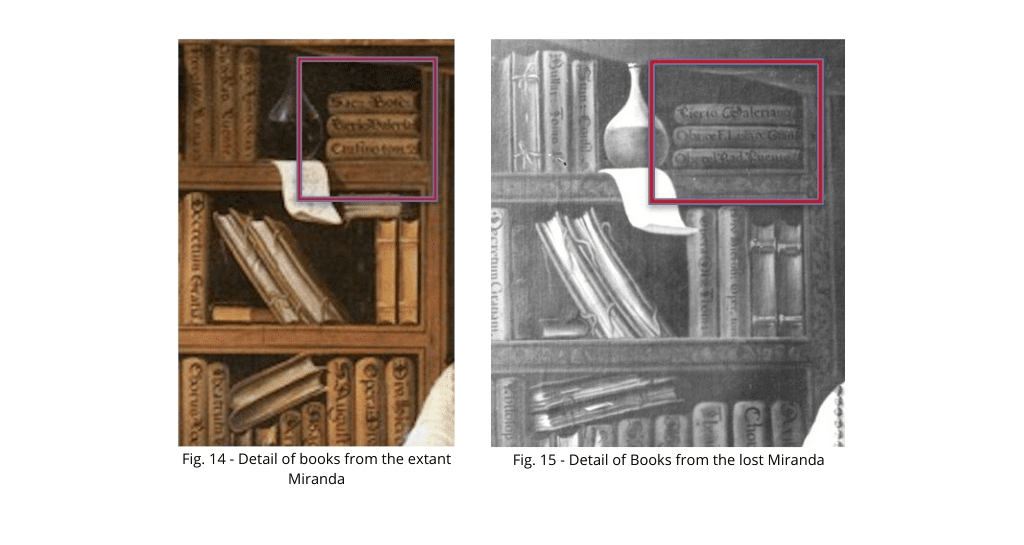

Reconfiguration of books and their groupings (figs. 14 and 15), the curl of the white piece of paper with its geometric notations and numbers, the positioning of the three volumes of Sor Juana’s works and inkwells and quill, and the biographical inscriptions’ designs – rectangular versus “V” shaped – as well as a flourishing versus a more restrained Requiescat in pace. And, of course, one inscription versus two. The biographical inscription in the lost Miranda matches Ágreda y Sánchez’s transcription perfectly, as does the short inscription written across the bottom of the portrait (fig. 13) that identifies Sister María Gertrudis de Santa Eustaquio. Miranda’s signature appears under Requiescat in pace in both portraits. The apparent absence of the geometric notations and numbers on the white sheet of paper and hardly visible lettering of the sonnet in the lost portrait is probably due to the nature of the photographic reproduction.

If the discovery of these photographs confirms that Miranda painted two portraits of Sor Juana – very similar with minor compositional variations – retracing their histories leaves several important questions unanswered. There appears to be no mention of Miranda’s extant portrait in the historical record until Flores Aguirre published his article and photo of it in 1944. Intriguingly, it is around the same time when the extant portrait’s existence is made known that references to the lost portrait disappear. So, where had the extant portrait been prior to its appearance in 1944 and where did the lost portrait go? Tracing their respective histories is further complicated by the disruptive impact of the Reform Laws in 1855 and 1856 that sought to disempower the Catholic Church in Mexico and the tumultuous decades that followed exacerbated by the Mexican Revolution. Confiscation of church wealth, the exclaustration of female convents and suppression of male religious orders resulted in the removal, theft, and destruction of many religious treasures, archives, paintings, and books. Nuns were forced to move to approved houses, or to stay with family or friends in the 1860s and ultimately many sought refuge in Spain in 1926 confronted with the anti-clerical policies of President Calles (1924-28). We know that the lost portrait hung in the Accounting Office of San Jerónimo from its commission in 1713 and was still there by 1750 when viewed by Cabrera. Where Ágreda y Sánchez viewed it in the 1890s, however, is unclear based on the vague description as in the possession of a nun of San Jerónimo. We assume that the extant portrait was also originally housed in the convent and remained there until the nuns’ exclaustration in the 1860s but where it was originally displayed in the convent is unclear.

Interviews with Mireles Espinosa and close friends provide contradictory accounts about how he acquired the extant Miranda (Tapia Méndez, 1993, 1995; León, 2012). What does seem clear, however, is that Mireles Espinosa’s great aunt, Sister Asunción Hurtado de Mendoza, an Heronymite nun, is the link between the extant portrait and how it came into his possession. Depending on which account one reads, either Sister Asunción deposited the extant portrait with a family directly for safekeeping or she asked Mireles Espinosa’s father (1891-1939), the former governor of Coahuila (1915-1917) to safeguard several works of art from the convent that included Miranda’s portrait of Sor Juana, before fleeing to Spain in 1926. Regardless, it appears that Miranda’s portrait was left with a family of “modest means,” possibly that of an antiquarian in Mexico City. Mireles Espinosa subsequently tracked down the portrait where “the canvas had been kept wrapped over a wooden support in some dank basement, so that its edges rotted” (Ruiz Gomar, 2004, 297). In all of these accounts, there is only one mention of two portraits by Miranda. Mireles Espinosa recounted that before leaving for Madrid, Sister Asunción related that “there were two portraits of Sor Juana by Juan de Miranda, not signed (Tapia Méndez, 1992, 216). Reference to the portraits being unsigned strikes an odd note, but the signature on the extant portrait is not immediately obvious. So, we have some idea of how Miranda’s extant portrait found its way into Mireles Espinosa’s private collection in the 1940s, but nothing substantive about its whereabouts prior to that journey. Similarly, we do not know what happened to the lost portrait after Ágreda y Sánchez viewed it in the 1890s, except to say that it had to have been photographed around that time for the subsequent cropped images to be published (the Mediateca dates of the photographs are catalogued as 1915 and 1940).

Confirmation of the second portrait’s existence clarifies the relationship between the extant (undated) and the lost (dated) portraits and should remove any confusion about the conflation of the two. It also creates a productive dialogue between the two portraits, one of which contains the enigma, while the other identifies the patron and the date of 1713. If the lost portrait honors Sor Juana by her “spiritual daughter,” Sister María Gertrudis, it also marks the occasion of the latter’s election as convent accountant in 1713. Evidence for this appears on the cover page of the second book of professions for the nuns of San Jerónimo dated 28 August, 1713, and on which her name appears prominently as accountant. As such, additional insight is provided into Sister Maria Gertrudis’s motivations to commission Miranda to paint a second portrait copied from the original one. It is no accident that the Accounting Office appears in both versions of the second inscriptions transcribed by Ágreda y Sánchez and Andrade.

Returning to Sigüenza’s hidden enigma, of the many differences between the two portraits that we have discussed, the books’ arrangements and their titles are of particular importance. Why? The presence of the enigma, its nature, and how to decipher it in the extant portrait is identified by the titles of the three horizontally grouped books on the right hand side of the top shelf (fig. 14). The uppermost book by Johannes de Sacrobosco (1195-1256). (Sac:Bosc) indicates that the enigma is calendrical in nature and is directly linked to the numbers and geometric notations on the white sheet of paper (fig. 1). The other two volumes by Nicolas Caussin (1583-1651) (Causino tom 2) and Pietro Valeriano (1477-1558) (Pierio Valer) signify that the enigma’s solution lies in the decipherment of the emblematic constructs represented by the other groups of books. Changing two of those titles in the lost portrait (fig. 15) effectively removed those signifiers that indicated the enigma’s existence, its nature, and how to decipher it. The new grouping of Valeriano (Pierio Valeriano) with Luis de la Puente (1554-1624) (Obr del Pad: Puente) and Luis de Granada (1504-1588) (Obr de F. Luis de Gran) not only removes the key role of emblems but also any reference to the importance of calendrics as signified by the presence of Sacrobosco’s volume in the extant painting. Without Sacrobosco’s work the enigma ceases to exist. The question remains whether this change was an intentional act on Miranda’s part or not? By 1713, signifiers for the hidden enigma have been erased from Sor Juana’s portrait as well as the possibility that only a handful of individuals – if that – knew that it ever existed.

Works Cited:

Abreu Gómez. Ermilo. Iconografía de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. México: Imprenta del Museo Nacional de México, 1934.

Andrade, Vicente de Paula, Ensayo bibliográfico Mexicano del siglo XVII. México: Imprenta del Museo Nacional, 1899, 483-485.

Burke, Marcus. Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Bullfinch Press, 1990.

Chávez, Ezequiel A. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: su vida y su obra (Barcelona: Casa Editorial Araluce, 1931).

González Obregón, Luis. “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” El Renacimiento, 15 April, 1894.

–––– México viejo. (Paris-México: Bouret, 1900).

Flores Aguirre, Jesús. Papel de Poesía, no. 16, January 1944.

–––– “Un retrato de Sor Juana,” Vanguardia, 3 February, 1944, 28, 77bis-78bis.

León, Jesús de. “Este que ves engaño colorido.” In Nací en el mero Saltillo. Crónica personal de figuras, casos y leyendas de mi localidad (siglos XVI-XX) (México: Saltillo Eres Tu. Programa editoral, 2012)

Maza, Francisco de la. “Primer retrato de Sor Juana.” Historia Mexicana 2/1 [5] (July-Sept. 1952): 1-22.

—— Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz ante la Historia. (Biografias antiguas. La Fama de 1700. Noticias de 1667 a 1892). Recopilación de Francisco de la Maza. Revisión de Elias Trabulse. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, 1980.

Paz, Octavio. Sor Juana or the Traps of Faith. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press 1988, trans. by Margaret Sayers Peden.

Perry, Elizabeth. “Sor Juana Fecit: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and the Art of Miniature Painting.” Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 7 (2012): 3-32.

Ruiz Gomar, Rogelio. “Miguel Cabrera. Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” In Donna Pierce, Rogelio Ruiz Gomar, Clara Bargellini, Painting a New World. Mexican Art and Life 1521-1821. Denver Art Museum; Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Salceda, Alberto G. “El acta de bautismo de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” Ábside, vol. XVI, (1952): 5-29.

Sánchez Moguel, Antonio,“Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Insigne poetista Hispano-Mejicano.” La Ilustración Española y Americana, 22 October, 1892.

Tapia Méndez, Aureliano. Carta de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz a su confesor. Autodefensa espiritual. Monterrey:Producciones Al Voleo El Troquel, S.A., 1993.

––––– “El autorretrato y los retratos de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.” In Memoria del coloquio internacional. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y el pensamiento novohispano 1995. México: Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura, 1995, 442-453.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.