On March 27th, 1873, still more than 1,600 miles from New York and with Liverpool just as far behind, John Godbold, a steerage steward aboard the steamship SS Canada, made a telling discovery. While sweeping “after steerage,” he “found in the waterway of the single women’s quarters a placenta (human). After some investigation,” the ship’s Official Log states, “a single woman named Mary O’Connor admitted she had been confined the previous night, + as her child was stillborn she had thrown it overboard. She was at once put in the Hospital under the Surgeon’s care.”

This is the extent of Mary O’Connor’s story as told in the Official Log. It holds clues, but no answers, about her and her child. It also illuminates some oft-overlooked truths: far from being markers of desperation, dissolution, or recklessness, pregnancy and childbirth formed ordinary parts of life at sea. They were accompanied by danger and sometimes death, but these, too, were hardly unknown aboard ship, where life and death went hand in hand for crewmembers and migrants.

The experience of migration—the decisions behind it, its major demographics, its rewards and tolls both physical and emotional—has been well studied. In both scholarly and popular depictions, death during migration is also a key theme. Yet migrant women’s experiences of giving birth at sea have received less attention, and the issues of childbirth and sexuality for women who worked at sea—especially side by side with their partners or spouses—very little attention indeed.

What follows will begin to tell that story. It will also reveal some of unexpected nuances. Responses to seafaring pregnancy and its associated risks varied more across class than gender lines. For working women, self-care in the course of pregnancy and childbirth was often out of the question. Their survival depended on risking death—for themselves and their children—to make a living.

Life at Sea: Romance and Reality

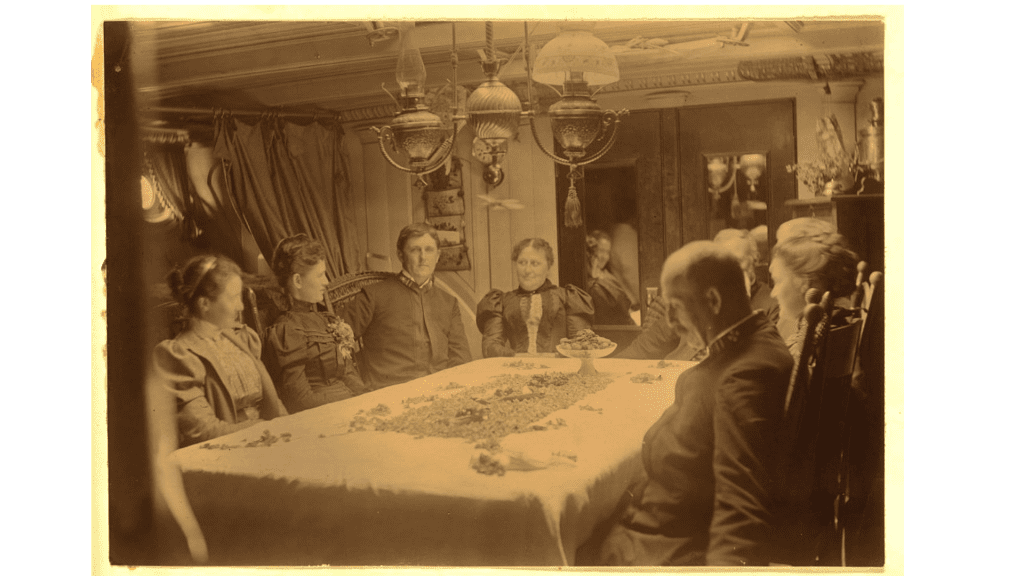

At the end of the nineteenth century, as the Age of Sail wound down under the pressure of steam technology, an upswelling of nostalgia re-characterized the great old sailing ships as representatives and nurseries of a heroic—and very masculine—Golden Age. By contrast, steamships, with their catering departments and cosmopolitan, mixed-gender crews, carried forward a new kind of empire, supposedly more “civilized” than the one dominated by the rough-and-tumble iron men and wooden ships of the past. Steamships allowed the ferocity of modern weaponry, of engines impervious to nature, to coexist with things traditionally linked to the comforts of home: women, children, and servants.

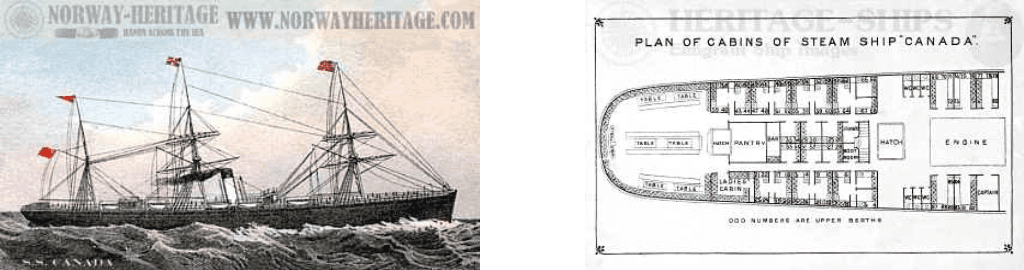

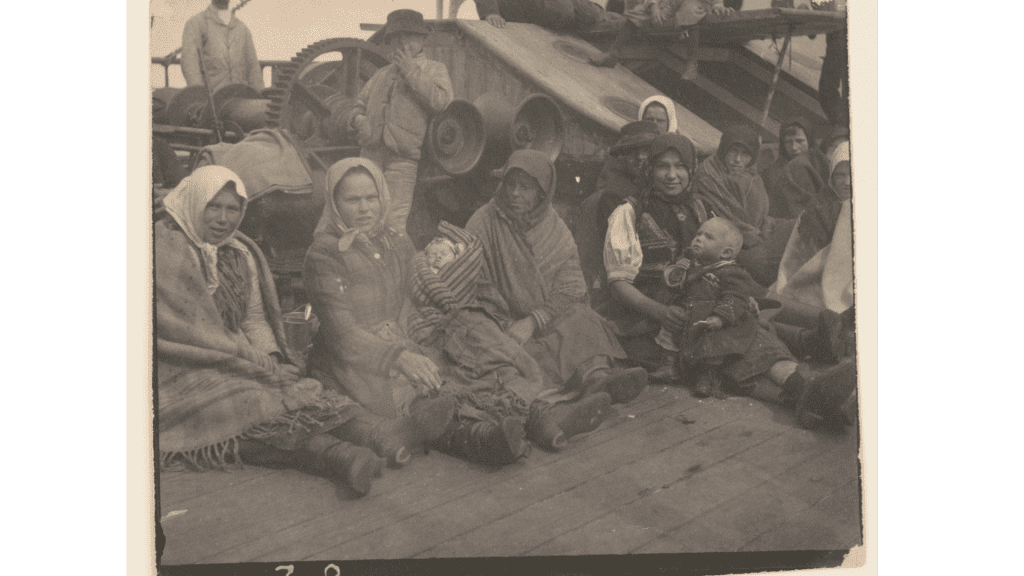

Consider the example of the Canada, the ship on which Mary O’Connor’s story took place. The Canada was an iron-hulled National Line steamship of 4,276 gross tons, almost 400ft long, capable of carrying 100 first-class passengers and 750 steerage passengers (steerage offering the cheapest tickets, often purchased by emigrants). O’Connor would have been one among the millions crossing the Atlantic to escape poverty or persecution, to reunite with family, to start a new life. But if so, she was doing so without a spouse—at least on the ship—and while pregnant.

The record of O’Connor’s pregnancy locates her in a particular part of the ship: the steerage deck. In a nineteenth-century steamship, steerage was a lower deck, enclosed and densely populated, without private cabins. At best, it contained groups of berths, sometimes only nominally separated from other groups in the same section. Men and women shared space aboard ship, particularly “public” places like saloons and on more luxurious ships, promenade decks, but only families could buy berths together. After 1850, the “after steerage”—the area towards the back of the ship where O’Connor’s placenta was found—almost always housed the single women. Families would be amidships, and the single male travellers were berthed forward, towards the bow, as far away from the single women as possible.

Vessels like the Canada defy the romantic narratives born of our assumptions about the Age of Sail. Those narratives tend to cast ships as homosocial heterotopias: worlds within worlds, intensely-experienced spaces inhabited by a single sex (in this case, men). According to sociologists like Erving Goffman, ships are also “total institutions” that restrict contact with the outside world, subject people to harsh, inflexible discipline, and place them under and constant surveillance. In places so crowded and so constantly watched, privacy is, at best, an illusion, and secrets—as, for example, the presence of a woman among the men—are impossible to keep.

To paraphrase German social theorist Heide Gerstenberger, it’s a shame Goffman ever read the work of Herman Melville, whose novels helped romanticize the supposed insularity of ships. Goffman’s analytical tools might be apt to describe some of the experiences of migrants and travellers at sea, but whether they hold true universally, especially for regular seafarers, is less clear. Romanticism overindulged in the idea of the heroic masculinity of the sailing ship, and self-regarding concepts of modernity overemphasized the fixed and immobile nature of society in the past. Ships were not as cut-off, as inescapably surveilled, or as single-sex as nostalgia described. While historians have long wrestled with these concepts, the payoff for throwing off the weight of nostalgia has only just begun. New fields of study, new sources, and new windows onto the seafaring past are complicating our ideas of about empire, society, and more in the modern era. Pregnancy at sea is one such window, revealing the complexity of sex, privacy, health, and risk as they weighed on the lives and choices of people of the past.

Women’s Health and Medical Practice

Technological change transformed life at sea during the late nineteenth century. Simultaneously, new ideas, practices, and discoveries transformed medical practice. Historians of medicine debate the effect of these changes on women: scholars like Ann Digby note that male medical practitioners began to find “biological” reasons for supporting subordinate social roles for women, binding them into a “biological straightjacket,” while others, like Clare Hanson, have argued that medical knowledge and social mores were intertwined, each affecting the development of the other. Medical practitioners interpreted many phenomena unique to female bodies, including menarche and menopause, as signs of weakness, indicators of inherent instability, and/or moments of particular vulnerability or frailty.

Contemporary medical discourse continues to “medicalize” and “pathologize” women’s health in ways that limit women’s rights. Medical knowledge frequently overlooks health issues unique to women, including pregnancy. Women have fought back in various ways—they have, for example, tried to publicize the extent to which heart attack symptoms present differently in male and female bodies, and they have also called attention to cases in which new medications haven’t been tested on pregnant women. However, over-medicalization tends to limit women’s input into their own medical care. Serena Williams has famously opened up about her experience following the difficult birth of her child, pointing out that women in general, and especially women of color, are disproportionately disenfranchised in the management of their own reproductive health with potentially fatal and life-altering consequences.[1]

It hasn’t always been this way. During the nineteenth century, prior to the medicalization of women’s health, authors of medical books, in the words of Ornella Moscucci and Ann Oakley, “constructed a schema of pregnancy which systematized what was taken to be the everyday experience of women.” As Rachael Russell argues, many aspects of and approaches to pregnancy were still individualized and culturally informed—pregnancy was seen as natural and not necessarily “treatable” in the way an illness was, an attitude drastically different from that of today.

Any idea takes time to disseminate, and medical attitudes towards pregnancy were no different. Treatment varied by class, and likewise, class and especially the privation that came with poverty affected both fertility rates and infant mortality. Many women could expect to spend a significant amount of their lives pregnant. In her study of nausea and vomiting, Russell, based on studies by Judith Lewis and many others, estimates that “many women could have spent around two years of their lives suffering from [morning sickness].” For middle- and upper-class women, pregnancy could mean more doctor’s visits, restriction of activity, and forced rest, but for working class women, pregnancy and work went hand in hand.

Being at sea—working, traveling, migrating, or in any other capacity— meant having the potential to be or become pregnant at sea. Before pregnancy became a fully medicalized condition, however, it was handled differently by different women, according to their social and cultural contexts. People who were pregnant were able to have a greater say in their own treatment; they also relied more heavily on their own knowledge and on knowledge produced within their own communities. But as a result, class politics played an important role in shaping individual pregnancies

Working Women, Maritime Marriages, and Pregnancy at Sea

Anyone who able to afford the tickets could embark on a transatlantic voyage; the same was true of anyone who could find work during the voyage. Women had always worked aboard ships in unrecognized or “unofficial” capacities, but at the start of the nineteenth century more and more women worked in the “official” position of stewardess. Single women, both unmarried and widowed, did work as stewardesses, though doing so would become increasingly scandalous as the century wore on. In time, mores hardened against the intermingling of the sexes, and the acknowledgement of sexuality—particularly as related to women’s sexuality or sexual desires—became more taboo.

Convict transportation in the eighteenth century had established the vulnerability of single women on ships, and especially in service on ships, to sexual exploitation. Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton, in their study of the formation of the “criminal Atlantic,” share a story recorded by a grammar school master who, in 1757, crossed the ocean with his family to take up a position at the College of William and Mary: “Do you remember how this tadpole of [a] captain promised that my wife could have one of the she-thieves to serve her whilst at sea? One of them is here in the cabin, but it was to serve this husband’s penis, and not to wait upon my wife, that she was brought here.”

Growing disapproval of such behaviour would result in a legal requirement for the separation of the sexes by mid-century. Even so, many captains preferred to pursue the less morally risky and more economical option of hiring married couples: the husbands as cooks, stewards, or in another positions aboard, and wives as stewardesses.

As Julia Bonham argues, the decision to travel or to migrate wasn’t always dependent on the man’s decision or the pressure of need on the family. Women were often active participants making choices, though their choices were complicated by a number of factors. Bonham describes them in terms of a paradox: on the one hand, wives bucked convention in insisting on engaging in life at sea, while on the other, they fulfilled the domestic ideal of staying with and supporting their husbands. Though seafaring women often picked up critical technical skills and experience, they were not usually considered “workers” aboard ship. Nevertheless, wives could feel hemmed in by labor-related concerns: the need to make money, provide for the family, and maintain employment on the one hand and by various risks—including risks arising from pregnancy—on the other.

One faithful helpmeet—a Mrs. Stephens (no first name recorded), who sailed as stewardess on the Evening Star, where her husband worked as a cook—experienced the paradoxes of life at sea first hand. She became ill on July 28th, 1868 while the Evening Star was docked in New Liverpool, Quebec. With the ship readying to leave port on August 2nd, she remained ill. The captain consulted with her husband, offering to pay them and let them off the ship, but “she refused to be left behind and wished to be kept on board and carried away to sea saying she would rather risk the dying on the passage the Captain then concluded to go to sea in the morning put one man (Charles Worrell, A.B.) in the galley to cook so that Stephens may attend to the wants of his wife.” By August 18, she was well enough that they could both resume their former stations, but such an act of generosity – taking someone aboard who was too sick to work and also allowing their companion off work to tend to them – was rare in the cutthroat world of merchant shipping.

Birth, Life, and Death Aboard Ship: Telling Women’s Stories

Since her voyage was only 10 days long, Mary O’Connor likely boarded the Canada either visibly or knowingly pregnant. However, what she or anyone else thought about the risks involved cannot be clearly connected to the decision to sail. As Alison Clarke has shown, some migrant women believed that the sea voyage would ease pregnancy and childbirth, but such feelings were far from universal. Going to sea may have, in some cases, increased pregnant women’s access to medical care, as any ships carrying over 100 persons—and all ships headed to Australia—were required to carried qualified surgeons. Notably, however, merchant ships generally were not (and are not) required to carry a surgeon, leaving women working aboard potentially on their own.

Ocean voyages were known to place infants at risk, too. Also on the Canada, just four days before the discovery of O’Connor’s placenta, Matze van Peyl, the two-month-old infant son of Guard and Nedge Van Peyl, died of “deficient vitality” and was “committed to the deep.” Sailing so soon after Matze’s birth, Guard and Nedge may have been waiting for Nedge’s pregnancy to pass before beginning their journey. Had they been sailing to Australia, the surgeon superintending the voyage might not have let them board with Matze, as regulators and medical professionals had already determined that young children were the most likely to die on emigrant voyages. Australia-bound ships therefore limited each family to not more than 2 children under the age of seven to lower mortality rates. On the comparatively less-regulated North Atlantic crossing, the risk devolved upon the parents. It was, potentially, safer to board pregnant, and hope not to have the child before landing, than to take even a young child on a long sea voyage.

Domesticity, however, could create an uneasy situation aboard ship by technically sanctifying sexual activity, of which childbirth was the inevitable proof. This was less true in the “family” sections of ships, where no suspicion would arise from even an unexpected birth even as single women faced intense social scrutiny. The situation was more ambiguous, however, for women working aboard ship—even if they were working with their husbands.

In one case from 1872, a married woman may have feigned illness to hide a pregnancy. H. J. Williams and his wife signed on the Henry Pelham as steward and stewardess while the ship was navigating the St. Lawrence River on July 1st. On July 10th, Mrs. Williams briefly stopped working, telling the mate that she was “homesick.” The next day, the log records that the stewardess told either the master or the mate’s wife that “she was sick with the monthlys and was afraid she was going to have a miscarriage.” On July 13th, Mrs. Williams took time off again, ostensibly due to pain in her back and head; the officers record that they offered her whatever medicines were wanted. Both the stewardess and her husband are recorded confessing that she might be “in the family way” on July 24th, and almost daily updates on her health—when and if she got up, whether she was moving about the galley, how she was feeling, and whether she took medicine—appear in the ship’s through August 4th. While not unprecedented, the detail and regularity of these logged updates possess an unusual solicitousness for what is usually a dry, sparse, official record of a limited number of events. One of the last log entries reported that “with fine weather at 8Am stewardess was not up asked the steward if she was sick he said she was not very well I told him that my wife had panes (x not very well) but felt better to get up and go on deck and no doubt but his wife would feel better she got up at 8:30 Am and was about the galley all the remainder of the day with her husband.” Such minute observations of daily activity, and unsolicited personal accounts and stories, are extremely unusual, and make the ultimate lack of resolution the more puzzling and dissatisfying. The log does not report a miscarriage, and offers no further detail once the stewardess reports she is “well again.”

Pregnancy posed risks in addition to the average risks of life at sea, particularly to stewardesses, though this does not seem to have deterred them from joining a ship’s company. Pregnancy could occur before and during voyages, but it wasn’t always identified correctly, and if it was, it wasn’t always reported to the master to be logged as such. Emma Dorsey, sailing on the Jesse Morris, went into premature labour and delivered a stillborn male at sea on May 18th, 1873. She was logged as “recovering slowly” on the 21st, and went back to work the 26th. May Ann Thomson, 34, of Aberdeen, boarded the Marco Polo on February 4th, 1859, and gave birth to a boy on September 13th, with no stoppage of work; she may not have known she was pregnant when she boarded, but surely would have noticed during the voyage.[2]

Even everything appeared “safe”—even when a stewardess was securely married and secure in her position—pregnancy would be kept secret. Such was true in the case of Grace Frank, a married woman hired to look after the pregnant wife of Norval Smith, master of the Birdie. The Birdie’s log records that, on December 12th, 1865, in Montevideo, Frank “resigned work . . . without any provocation whatever for which I stop pay”—stoppage of work often equaled a stoppage of pay—and “to this date she remaining [sic.] on board idle.” Once the ship was at sea, on February 13th, 1866, Frank took sick, with the captain applying a variety of curatives including calomel and quinine with a light diet. At noon on March 1st, “still bad” and attended by her husband (most likely the boatswain John Frank), she had a miscarriage.

On the 14th, Norval Smith’s wife Margaret, the woman whose presence aboard the Birdie had led to Grace Frank’s employment, gave birth to a boy named Fernando. Grace Frank died at sea that same day.

Did Grace Frank board knowing she was pregnant? She and John joined in September 1865; it seems more likely she became pregnant during the voyage. Once her pregnancy made it too difficult to work, she stopped. Perhaps she did not know at the time that she was pregnant, or perhaps sickness seemed like a more appropriate, acceptable, or responsible reason to stop working than pregnancy.

Many of the women who crossed the Atlantic while pregnant survived the voyage, as did many of their children – but many others didn’t. Mortality rates for pregnant women and for young children were both higher at sea than on land, despite help often being closer at hand on ships, which were very early on required to have surgeons aboard. Frank kept her secret, and died; the long dance of inquiry and demurral on the Henry Pelham may or may not have been to preserve conjugal privacy, or just economic security. The Van Peyls made a choice which cost them dearly. Perhaps Mary O’Connor did as well: a single woman in close company would be under intense scrutiny, and her behaviour aboard could affect her prospects on land. The Log only records that she reported the child stillborn, but perhaps her pregnancy wasn’t the secret she had been so eager to keep. Short of finding her own account, we can only guess; the Official Log, on which the whole weight of social authority and approval rested, which would be returned to the government and preserved for more than a hundred years, is an unreliable witness.

Secrecy and scrutiny, along with poverty,

amplified the dangers of pregnancy at sea. In some cases, it killed pregnant

women and their children.

Sources and More Information

Archival sources:

The Crew Lists and Logbooks Collection at the Maritime History Archives, Memorial University, Newfoundland, Canada.

Secondary sources:

Bonham, Julia C. “Feminist and Victorian: The Paradox of the American Seafaring Woman of the Nineteenth Century.” The American Neptune 37, no. 3 (1977): 203–18.

Digby A., ‘Women’s Biological Straitjacket’, in Mendus S. and Rendall J. (eds), Sexuality and Subordination: Interdisciplinary Studies of Gender in the Nineteenth Century (London: Routledge, 1989), pp. 192-220.

Gerstenberger, Heide. “Men Apart: The Concept of ‘Total Institution’ and the Analysis of Seafaring.” International Journal of Maritime History 8: 1 (June 1996): 173–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/084387149600800110.

Hanson C., A Cultural History of Pregnancy: Pregnancy, Medicine and Culture, 1750-2000 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Lewis J.S., In the Family Way: Childbearing in the British Aristocracy, 1760-1860 (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1986).

Morgan, Gwenda and Peter Rushton, Eighteenth-Century Criminal Transportation: the Formation of the Criminal Atlantic (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004).

Moscucci O., The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England, 1800-1929 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Oakley A., The Captured Womb: A History of the Medical Care of Pregnant Women (Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher Ltd., 1984).

Russell, Rachael.

“Nausea and Vomiting: A History of Signs, Symptoms and Sickness in

Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Ph.D., The University of Manchester (United

Kingdom). Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1774234326/abstract/9F3608E0CC194381PQ/1.

[1] Rob Haskell of Vogue interviewed Williams about her experience, but she has given multiple interviews about her experience: https://www.vogue.com/article/serena-williams-vogue-cover-interview-february-2018

[2] The father was listed on the agreement only by first name, “William,” but the only William Thompson apparent on the agreement was a seaman who deserted in Melbourne in July of that year; Ann was discharged with “very good” ratings in Liverpool in October. While this could be a case of abandonment, it seems more likely that the stewardess was a passenger given free passage in exchange for her work, but in this case, the lack of last name for the father would be unusual.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.