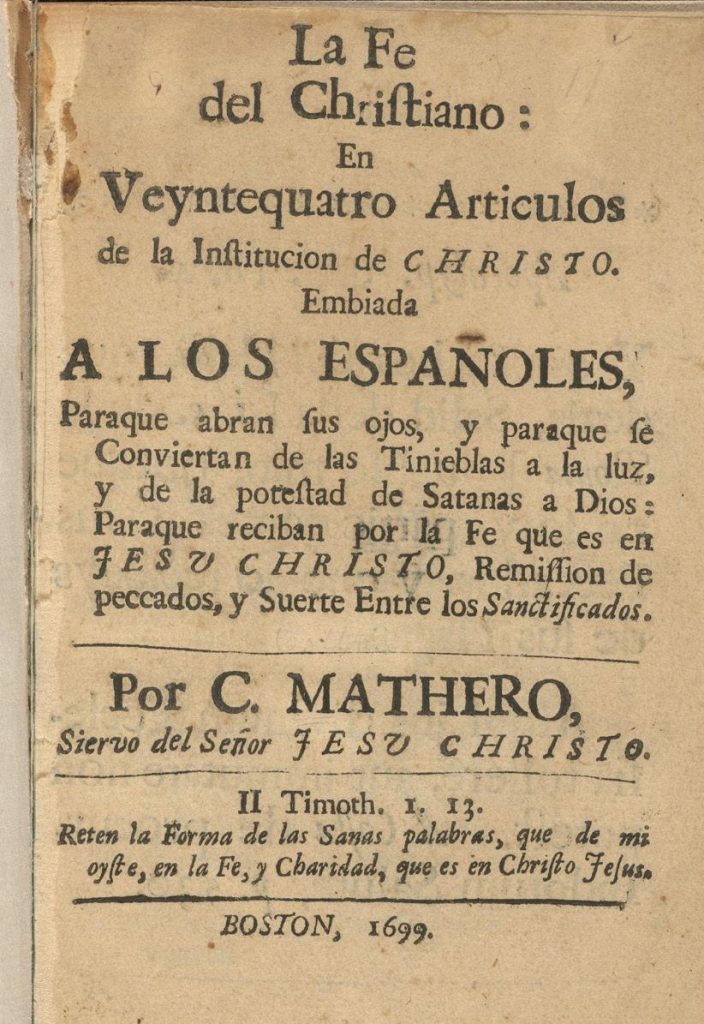

In 1699 Cotton Mather published a 16-page catechism in Spanish, La Fe del Christiano.

The only three surviving copies reveal a hastily printed catechism riddled with improvisations and errors. To get an “ñ,” as in Señor (Lord), the anonymous typesetter split a fragment of a double long “ff” serif.

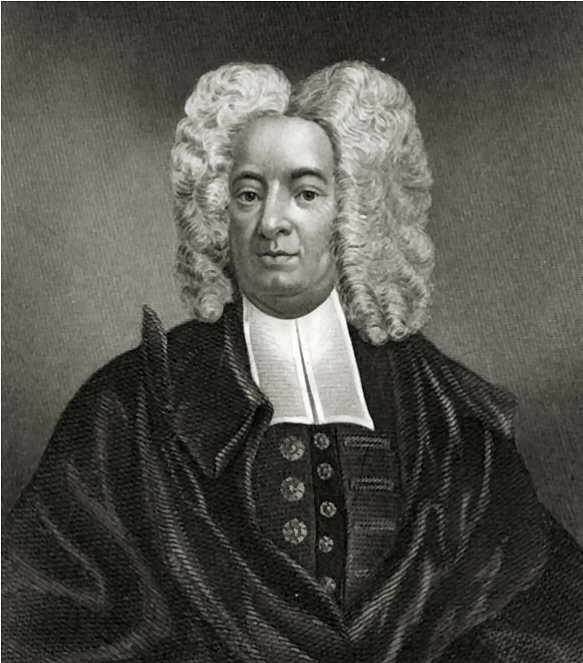

Mather’s catechism was printed in miniature: on an eighth of a folded page with one letter page per catechism. In an important new book, Cotton Mather’s Spanish Lessons: A Story of Language, Race, and Belonging in the Early Americas, Kirsten Silva Gruesz has examined the origins of this tiny piece of ephemera, one of 4,000 titles written by Mather, including the ten-volume Biblia Americana.

Who was the intended audience of Mather’s catechism? How did Mather learn Spanish? Seeking to answer such seemingly simple questions, Gruesz uncovers the extraordinarily complex racial universe of early eighteenth-century colonial Boston. Using the little-known history of this ostensibly disposable item, Gruesz boldly explores the colonial origins of “Latinos” in Anglo America.

To be sure, there were no “Latinx” in Mather’s Boston. Gruesz, however, focuses on the many “Spanish Indian” and “Spanish Negro” slaves serving Puritan households. These early modern captives not only lacked names, but they also embodied ambiguity. What did “Spanish” mean? That they were Timucua captives driven from Florida missions by the Westo and Yamasee allies of South Carolina planters? That they were maroon Spanish captives from Jamaica? That they were Angolans that shared common ethnic Catholic markers with “Spain”? That they were “Spanish-speaking” captives introduced in Boston by the numerous Portuguese conversos relocating from Olinda, Curaçao, and Surinam? Gruesz argues that these are the same ambiguities of belonging that Latinos face today. Latinos, she maintains, are the nation-state descendants of the mongrel, “Tawny,” and “Spanish-speaking” populations that Mather sought to address. They are, in other words, unclassifiable in the traditional White-Black racial dichotomies of Anglo-America.

Gruesz suggests that Mather learned Spanish from the various nameless “Spanish” Indian-Negro slaves in his household and that the catechism was addressed to similar individuals on the continent. Mather’s project, Gruesz argues, was one of conversion not unlike that of the Franciscan missionaries with the Timucua in Florida or John Eliot with the Wampanoag in the praying towns of Massachusetts. Mather introduced La Fe del Christiano citing Acosta’s Procuranda Indorum Salute (1589–in English, How to procure the salvation of Indians), an influential Jesuit text on missions that argued for the use of indigenous vernaculars in conversion.

Acosta was responsible for putting together catechisms, confessional manuals, and sermons in Quechua and Aymara during the Third Council of Lima, which took place in the1580s.

Mather uses Acosta to argue that it was a “right” of people to hear the word of God in their own tongues. This basic Protestant tenant was, however, tested by King Phillip’s War, which pitted Puritans against the Wampanoag, the very people who the “apostle” Eliot had sought to convert. It was Mather himself who put an end in 1700 to all further printing of Wampanoag bibles and catechisms.

Gruesz suggests that the “mongrel,” “tawny” castas of the continental and Caribbean Spanish “frontier” became Mather’s new mission target. Gruesz draws on Mather’s and Mather’s friend, Samuel Sewall’s, chiliastic publications to make her case.

Clearly, Calvinists like Mather and Sewall thought that end of times was near, provided that all Jews were converted. Since Indians were the lost tribes of Israel, their conversion would hasten the apocalypse. In Sewall and Mather’s rendition, “America” would be the place of the millennium, not the rearguard of Satan from where the armies of Gog and Magog would attack the elect–as suggested by previous Puritans divines. This chiliastic vision had prompted Cromwell in 1650 to send a massive armada to conquer the Spanish American empire. Cromwell expected oppressed Black slaves, maroons, and Indians to join the English in a liberating crusade against the cruel “Spanish.”

To their surprise, the “tawny” masses turned against the English, routing Cromwell armadas in several humiliating defeats. It turns out, “they” were the “Spanish.” This Western Design however left the English in control of tiny Jamaica, a smuggling entrepot perfectly positioned to secure access to Spanish silver, which became the engine of Boston’s commercial prosperity. Gruesz argues that Mather and Sewall sought a less violent assault on the evil Catholic empire, this one spearheaded by cheaply printed catechisms.

Drawing on a careful reading of Mather’s diaries, letters, and autobiographies, Gruesz masterfully reconstructs Mather’s household and millennial dreams. There is a disconnect between Mather’s grandiose geopolitical crusading aspirations and the scale of his output, one miserly, badly printed catechism. The tiny size of the catechism might have served to help smuggle Calvinist dogma into the Spanish Caribbean. Yet it was a cheap, hastily printed document full of grammatical, orthographic, and syntaxial errors. Like Cromwell, Mather was deeply condescending to his audience of “Spanish-Indian-Negros.” Given this basic fact, it seems to me that we could more productively focus on Cromwell’s and Mather’s condescension and what exactly it prefigures. It was not “mosquitoes,” John Robert McNeill notwithstanding, that ultimately defeated the British in Cartagena in the War of Jenkins Ear or in Cuba and the Philippines in the Seven Years’ War or in Buenos Aires in the failed attacks of 1806 and 1808. Every time the British sent armadas to Spanish colonies to help set “Indians and Negros” free (to become consumers and pliant labor), the British were routed by “Indian,” “Negro,” and “casta” armed militias.

There is a dimension of Latinidad in this book that invites further exploration: Mather’s Indians and Negros were “Spanish” because they were foreigners. This is what made them “Latinos.” The English, including Mather, never considered those that they called “mongrels” as part of a political nation. In this, they differed from the “Spaniards.” “Tawnies” were foreigners. Identity in English America was not religious but always ethnic. Portuguese conversos in Boston could be English. Blacks and Indians never. Free Blacks remained Africans, whether in late 17th-century Cambridge or in 19th-century Boston. Black churches, clubs, and athenaeums remained “African” until the New Negro movement. What happened to “Africans” happened to “Latinos” too. It took centuries until the landmark 1954 Hernández v. Texas case for Mexicanos (Tejanos born in the U.S.) to gain some rights of citizenship. They finally became hyphenated Mexican-Americans almost 90 years after Reconstruction. This heavy colonial legacy is what begat “Latinos.” This is what keeps one million “Latinx” English native speakers, early childhood arrivals to the U.S., as foreigners. And it applies even to individuals born in this country. Throughout his twelve years of elementary, middle and high school education, my U.S.-born son has had to prove every year to both Federal and State governments that he is in fact a full American. He was classified in kindergarten as an “English Learner” because of his bilingual background. It is difficult to escape the obvious conclusion: that he is being socialized by the wider system to believe that he is somehow deficient. He is, therefore, a full-fledged Latino.

Kirsten Silva Gruesz has produced a masterful study that should be widely read. But there are more questions to be asked of this text and the attitudes that gave birth to it.

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra is the Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin and the Director of the Institute of Historical Studies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.