I was on a train listening to the podcast The Road to Now and I couldn’t stop laughing. The hosts joked about 19th-century drunken slogans, American daredevil Sam Patch, a feud fought by jumping off Passaic Falls, and a ship with an effigy of Andrew Jackson sent over a waterfall. [1] As I stifled my laughter, it became clear that there was much more to the story. The podcasters explained Patch’s bizarre journey to becoming one of the United States’ first ‘common man’ celebrities during the onset of the Industrial Age, a narrative also explored in Leaps of Fame: The Rise of Sam Patch and a Changing Industrial Landscape.

To better understand Sam Patch’s life in the context of 19th century working-class culture, I set out to make a ClioVis timeline. ClioVis is an interactive timeline software that allows you to chart, and emphasize connections between, historical concepts, events, and themes. My project incorporates The Road to Now’s podcast episode on Patch, allowing users to hear audio clippings of the podcast. Additionally, I relied heavily on Paul E. Johnson’s research in his excellent book Sam Patch: The Famous Jumper. Not many records exist on Sam Patch, especially preceding his fame, and Johnson’s book is the product of extensive research.

Patch life’s offers a fascinating window into a crucial moment in US history as industrial change transformed literal and cultural landscapes. Born around the turn of the 19th century, Patch spent his youth navigating a shifting landscape of worker identity in New England. He worked as a skilled laborer in various textile mills and, in Paterson, New Jersey, even joined the Paterson Association of Spinners.[2] Outside of work, he quickly began mastering the art of jumping from high places.[3] Thousands of people gathered to watch Patch’s leaps, but his story goes beyond showmanship. Studying his life as a performer reveals how class-status determined access to natural spaces and illuminates the rise of the American daredevil celebrity.

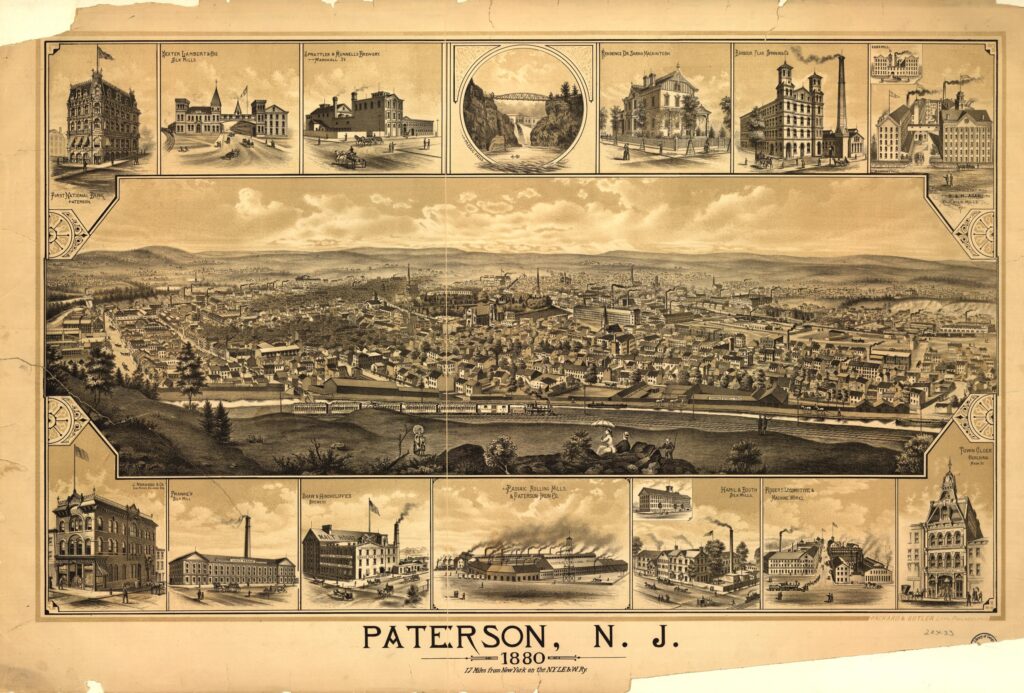

The United States’ emerging Industrial Revolution provided the backdrop to Sam Patch’s life. At the time of Patch’s birth, the United States’ first water-powered mills were not even a decade old. In Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Samuel Slater opened the country’s first water-powered textile mill in 1793.[4] This style of mill would eventually transform New England’s waterways as entrepreneurs sought to harness the power of water for industrial production. In Paterson, New Jersey, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.) built an industrial city that Alexander Hamilton hoped would define the United States’ industrial landscape. Paterson Mill—eventually water-powered—opened in 1794.[5]

Patch worked in both of these industrial centers before becoming a daredevil. In Pawtucket, Patch found joy and escape by jumping in the Blackstone River with other children, where he began learning the art of high dives. In 1824, Pawtucket was the site of the nation’s first factory strike. Limited evidence makes it difficult to know if Patch took part in the strike. Regardless, he witnessed the formidable power of Pawtucket’s mill owners who colluded in setting working conditions to limit competition and maximize profits.[6] His time in Rhode Island helped form his sympathies for New England’s working-class.

In 1826, Patch moved to Paterson, New Jersey where he would perform a jump designed to antagonize local businessman Timothy Crane over his use of public land. Patch and his fellow spinners frequently enjoyed the Passaic River recreational area. In contrast, Crane built a park called “Forest Garden” which featured a curated selection of plants for the enjoyment of the city’s elite. For a fee, people could enter Crane’s new park which used to be the site of a public playground.[7] In September 1829, Crane promoted the installation of a bridge across Passaic Falls to his new park. Patch intentionally chose to organize a leap to coincide with the unveiling of this bridge. Crane, hearing of these plans, worked with the police to lock Patch in a basement with Patch’s other favorite pastime: the copious consumption of alcohol. Despite this effort, Patch found a way to freedom and jumped from Passaic Falls right as Crane placed the bridge.[8] As planned, Patch stole the large crowd’s attention. Perhaps unintentionally, Patch also started his path toward becoming the United States’ first famous stuntman.

By jumping at the same time as Crane’s bridge unveiling, Patch staged a public show of resistance to Crane’s attempt to privatize land and regulate the recreational use of natural spaces. We may understand Patch’s jump as highlighting two important concerns that came to define his career as a showman: the public use of natural spaces and his sympathy with New England’s working-class. Patch brought entertainment to public audiences and championed the use of natural spaces for common enjoyment. Crane, on the other hand, created his “Forest Garden” in an attempt to make recreational areas more exclusive.

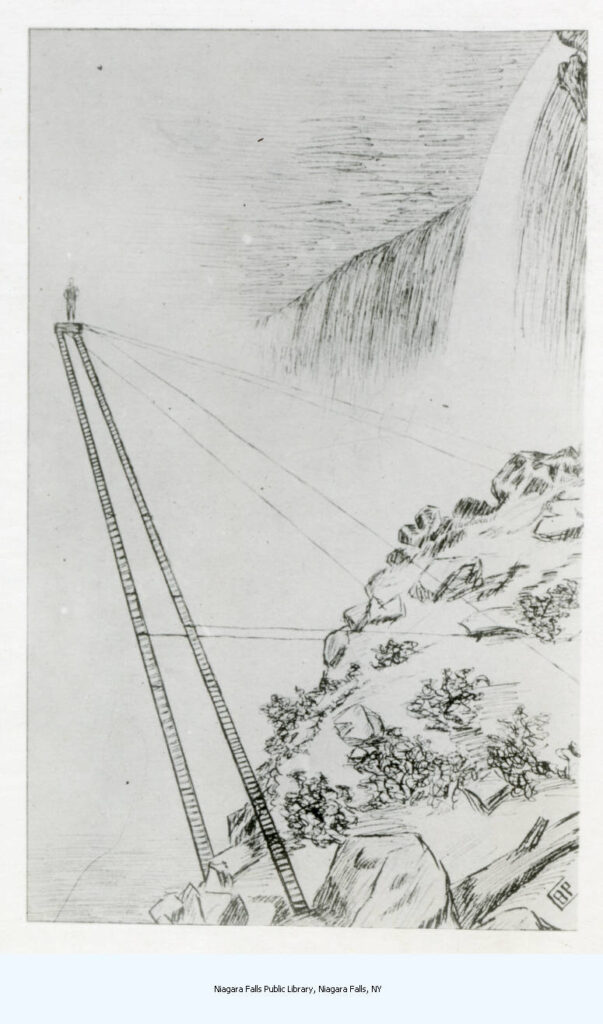

By fall 1829, Patch had become famous and regularly attracted audiences of thousands. Invited to an event celebrating ‘the Niagara Frontier,’ Patch headed to the falls in early October. He planned to jump his highest jump yet off of a platform on Goat Island—a site in between the United States and Canadian Falls. Patch arrived late which led the organizers to delay his jump by a day. When the date came, he had a drink and prepared to throw himself from the prepared platform. As per his routine, Patch wore his Paterson Association of Spinners uniform during his jump.[9] He leapt from the platform and gracefully landed in the pool below. His audience cheered as he emerged from the water. Patch went on to do another jump at the falls just 10 days later. These events further strengthened Patch’s fame.

As Historian Paul E. Johnson argues, Patch was one of the first ‘common men’ to reach celebrity status without significant wealth or ties to positions of great authority. In his words, Patch “wanted to be famous and he succeeded”, a fear that was far from common at the time.[10] In this way, he represented many aspects of the Jacksonian Era. His rise to fame mirrored the ideals that President Andrew Jackson and the Democrats promoted—an image of opportunity and success available to supposedly “ordinary” white male Americans.

My ClioVis timeline expands on Sam Patch’s story while better situating it within the context of the early 19th century. Using the ‘categories’ feature, I organized my timeline into cultural history, labor history, and the events of Patch’s life. The software also allows me to incorporate images, audio clippings, and ‘connections’ to strengthen my argument. These features enabled me to create a complex chronology of Patch’s life.

Sam Patch ended his career with a fatal jump into the Genesee River in 1829—yet, his legacy lives on. Following his death, Patch’s name entered into the colloquial lexicon. “What the Sam Patch,” “Where the Sam Patch,” and “Some things can be done as well as others” all became common sayings.[11] President Jackson named one of his horses Sam Patch, and the actual Patch became a character in countless theatrical productions and literary works across the world.[12] Today, Patch’s life offers us a platform to jump off for a deeper understanding how the Industrial Revolution changed natural and cultural landscapes in New England. His story provides insight into how capitalists and workers varied in their approaches toward using public land. Finally, examining Patch’s rise to fame tells us something about how Patch and the Jacksonian Era ushered in new ideas of the ‘American celebrity.’ Patch claimed physical space—through his jumps and their audiences—for the working-class on public land and in peoples’ minds as a ‘common man’ celebrity.

Aidan Dresang is an undergraduate history major studying to become a public high school history teacher. He is interested in environmental history and resistance movements. As a future history teacher, Aidan hopes to teach history critically and bridge the community-classroom divide. He is currently a ClioVis intern.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Banner photo by Anthony Rodriguez.

[1] Rivers Langley, Narado Moore, and Ben Sawyer, “Sam Patch: America’s First Daredevil,” The Road to Now, accessed July 15, 2024, https://open.spotify.com/episode/3qHTRGbVgsrML2z5nYmtAL?si=c6bbc181cf284adb.

[2] ‘Spinners’ refers to workers who made thread, often using the ‘spinning jenny.’ The adoption of power looms in textile production mills often led to the displacement of skilled textile workers (spinners).

[3] Paul E. Johnson, Sam Patch, the Famous Jumper, 1st ed (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2003).

[4] National Park Service, “Slater Mill,” National Park Service, July 13, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/blrv/learn/historyculture/slatermill.htm.

[5] National Park Service, “The Birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution,” National Park Service, January 12, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/pagr/learn/historyculture/the-birthplace-of-the-american-industrial-revolution.htm.

[6] Gary Kulik, “Pawtucket Village and the Strike of 1824: The Origins of Class Conflict in Rhode Island,” Radical History Review 1978, no. 17 (May 1, 1978): 5–38, https://doi.org/10.1215/01636545-1978-17-5.

[7] Paul E. Johnson, Sam Patch, the Famous Jumper, 1st ed (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2003), 48.

[8] Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck, “The Real Simon Pure Sam Patch,” Rochester History, 1991.

[9] Janet M. Davis, “Proletarian Daredevil,” ed. Paul E. Johnson, Reviews in American History 32, no. 2 (2004): 176–83.

[10] Johnson, Sam Patch, the Famous Jumper, 164.

[12] Langley, Moore, and Sawyer, “Sam Patch: America’s First Daredevil.”