This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

Today, when a book is outdated or simply no longer wanted, it heads to a secondhand bookstore, a friend, or sometimes, a dumpster. In the early modern period, however, the leaves of unwanted books frequently became ripe candidates for recycling. (A leaf is what you turn in a codex-form book; each has two sides—two pages.) These leaves, determined to be “waste,” were used in the construction of new bookbindings.1 Such waste frequently turns up in the Harry Ransom Center’s collection. A third edition of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1628), for example, is bound with printed waste from the Apocrypha in unidentified small-format edition of the King James Bible translation. In another instance, a Book of Common Prayer (1549) utilizes parts of a thirteenth-century manuscript as pastedowns, glued to the inside of the book’s front and back covers.2 In some cases, waste is the only material evidence of a text that survives today, and thus serves as a mechanism of preservation. As Adam Smyth writes, “Often, an institution’s response to printed waste—to remove or maintain? to catalog or ignore?—is a useful indicator of the waste text’s cultural standing at that moment.”3

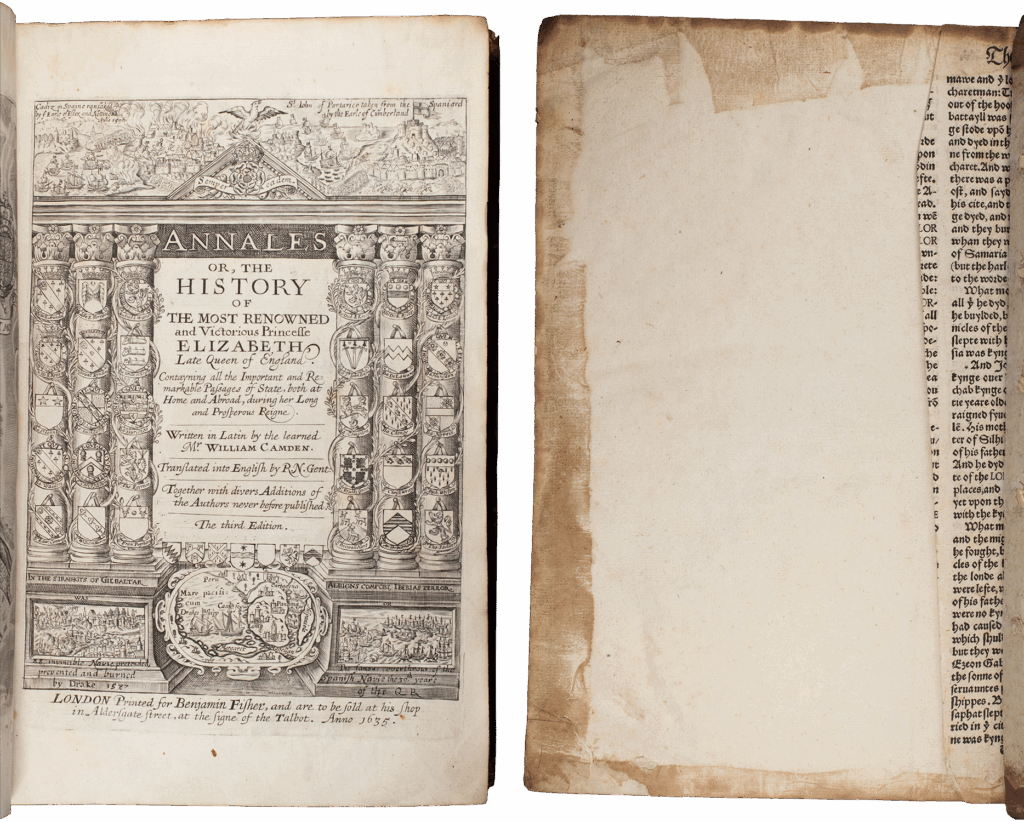

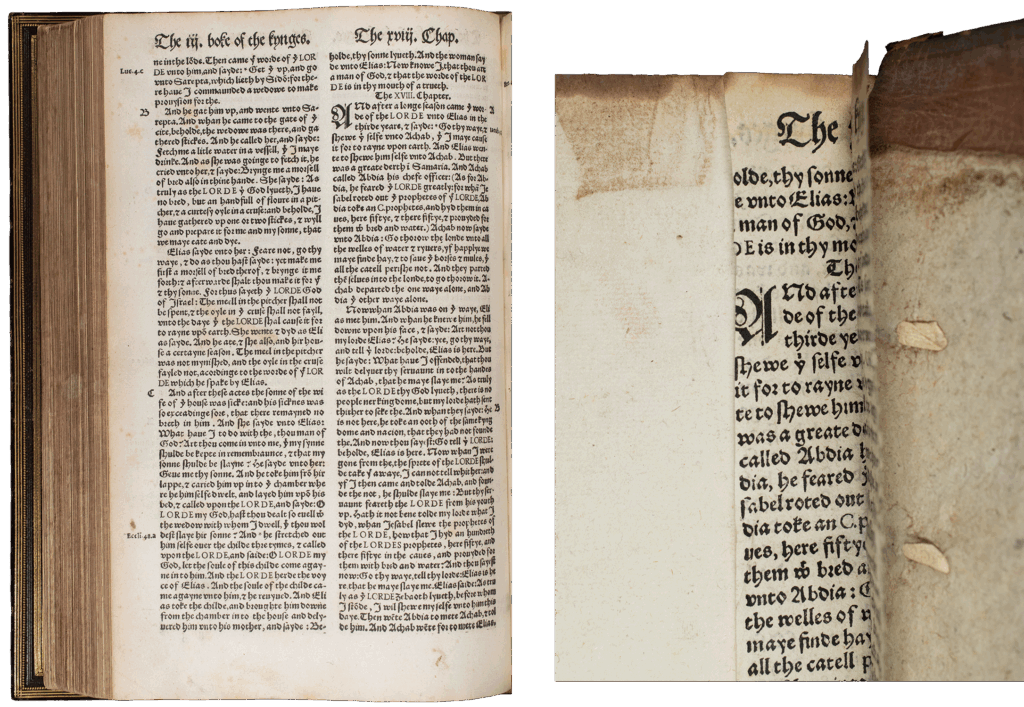

The Ransom Center recently acquired an early history of Queen Elizabeth I, a third printing of the Annales by William Camden (1635). The Center did not have a copy of this exact edition, so the volume helpfully filled a gap, but it was primarily attractive because it uses scraps from a Coverdale Bible (1535)—the first full bible printed in the English language—as binding waste, parts of leaves from III Kings (I Kings in most Protestant bibles). While the Center has long held copies of the landmark book, one receives a particular history of the early modern English bible from the fragments; preserved in the Camden, they become a kind of sedimentary record from a century earlier. Around 1635, an old Coverdale could apparently just be seen as waste. Today, though, any part of a copy would be attractive to collectors. In 1973, a Coverdale Bible missing 24 leaves sold for $50,000; today this translates to roughly $353,000 (there are no known complete copies).4 At the time of writing, AbeBooks lists another copy for a cool $1.5 million, describing the book as “the finest known copy in private hands.”5 There’s also a healthy market for individual leaves. In 2022, one Coverdale leaf sold for $780. To compare, a complete 1635 Camden usually sells for around $1,000.6

Given the religiosity of early modern England, it might seem sacrilegious that someone would slice up a sacred text like the bible. The re-use of religious texts in new books, though, has a long history.7 And when it comes to bibles in particular, it is important to remember that the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were an era of consistent and very public changes in what the “correct” bible should be. One that was popular and expensive in 1535 did not necessarily retain its value in 1635. Even in its own century, the Coverdale quickly gave way to the new-and-improved Matthew, Taverner, Great, Geneva, and Bishops’ Bible translations.8 In 1611, the King James became the official version in parishes and quickly found its way into households across England. This was the case in 1635, when the third edition of Annales was published. Despite Queen Elizabeth I’s famous statement that, “There is only one Christ, Jesus, one faith. All else is a dispute over trifles,”9 bible translations could be hotly contested, depending on which monarch was on the throne and which factions had influence. Religious and bibliographic turmoil often go hand in hand.10 The fact that a Coverdale was used as part of a binding speaks, perhaps more than anything else, to the ubiquity of outmoded bibles by 1635. The fragments in the Camden almost certainly came from a copy of the book that had circulated—and probably sustained significant damage—and not from unbound sheets that had been languishing in a warehouse for 100 years. This damaged-yet-durable quality of early modern bible leaves made them ideal for strengthening new books.

The third edition of Annales was published only seven years before the English Civil War began in 1642, during a period when tensions within English Protestantism were growing. Given the morphing religious and political climate, it is tempting to read the relationship between biblical waste and its host text in a poetic or reciprocal manner, to say that the two texts—by their mere physical proximity—must be in conversation with one another, whether synergistically or antagonistically. As Smyth writes, “Waste thus complicates or thickens the historicism of the text, since to read waste is to be aware of multiple temporalities.”11 III Kings is about Davidic succession. At one point, David’s attendants try and find a virgin to look after him; Queen Elizabeth was commonly known as the “Virgin Queen.” III Kings is also a history and depicts Solomon building up a navy; Queen Elizabeth crucially expanded Britain’s naval and thus colonial power. Stories such as these appear frequently in the Bible, however, and there is zero reason to think that the binder intended a meaningful juxtaposition, especially given that the Coverdale components are scraps with incomplete sentences. Nonetheless, the two texts’ proximity can serve as a snapshot of English culture at the moment they came together. Camden’s retrospective history of Elizabeth offered nostalgia in a period of increasing turmoil under Charles I, and the Coverdale Bible was not in popular use. Both were facts around 1635.

So, when did a first-edition Coverdale make the transition from plausible binding support to collector’s item? “Protestant revivalism from the 1780s, followed by Catholic renewal from the 1830s, combined to give a new religious aesthetic to Christian practice in Britain,” one where objects such as bibles become renewed sites of devotional sentimentality.12 The British and Foreign Bible Society had been founded in 1804 to ensure that every household was able to procure a bible.13 On the one hand, this meant that bibles became more commonplace. On the other, more attention to English bibles in general made some editions special, helping turn them into monuments of the English Reformation. Even collectors more focused on literature, such as the American banker Carl H. Pforzheimer (1879-1957), came to see bibles as essential to a high-quality collection. The Ransom Center acquired its second 1535 Coverdale when Pforzheimer’s pre-1701 English books and manuscripts arrived in 1986. With the Camden, part of a third has joined the collection.

Kōan Brink is the Graduate Research Assistant for Early Book and Manuscripts at the Harry Ransom Center and a doctoral student in the Department of English at UT Austin. Their research focuses on early modern England— particularly poetry—religious texts, bibliography, and the history of the book.

1 Adam Smyth, “Printed Waste: ‘Tatters Allegoricall’,” in Material Texts in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 137.

2 Harry Ransom Center, PR 2223 A1 1628 and -q- BX 5145 A2 1549c.

3 Smyth, 152.

4 Measuring Worth, accessed September 28, 2025, https://measuringworth.com.

6 “Rare Book Transaction History Search Results,” Rare Book Hub, accessed October 10, 2025. (Access requires subscription.)

7 Anna Reynolds, “‘Such Dispersive Scattredness’: Early Modern Encounters with Binding Waste,” Journal of the Northern Renaissance 8 (2017).

8 John N. King and Aaron T. Pratt, “The Materiality of English Printed Bibles from the Tyndale New Testament to the King James Bible,” in The King James Bible after 400 Years (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 74.

9 “Elizabeth I,” Newberry Library, accessed September 24, 2025.

10 Reynolds.

11 Smyth, 153.

13 Ibid.