by Stephen Panico

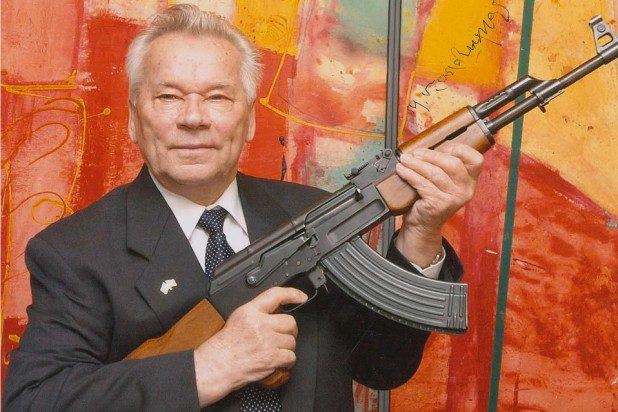

It is a curious device. Standing on a pedestal surrounded by a crude plaster diorama of a workshop is a medley of parts fashioned into a strange upright apparatus. There is a small collection of wooden poles and netting at the back, connected to a base of long spindled metal that seems it would collapse with even the most rudimentary use. This, in turn is welded to a cylindrical front piece that appears to have rake tines jutting forth from it. The entire contraption is connected to a set of wheels that look borrowed from a child’s bicycle. Indeed, it looks like a child’s idea of a lawn mower, improved in ways that altered its appearance but with dubious affect on its function. This device, according to the placard that accompanies it in the museum near Izhevsk, Russia, is a lawn mower. Surrounding it are hundreds of AK-47 assault rifles. The museum is devoted to the inventor of both, Mikhail Kalashnikov, who died on December 23, 2013 at age 94. The primary feature of the museum is most certainly the myriad variations of Kalashnikov’s rifle. Wood and stamped steel along with individual placards describe how this or that minor feature offered diversity to a weapon that, in the modern world, is just about the most diverse around. There are of course many images of Kalashnikov himself. Holding the weapon. Personally presenting variants to front-line soldiers and guards who have performed admirably. Wearing full general regalia and beaming. The juxtaposition of this man, the expert weaponsmith, alongside some of his dramatically lesser known inventions is stark. The man who built the rifle that has been used to take more human lives than any other in history was a tinkerer who liked to improve things, even if it made them appear rough or rudimentary to an outside observer.

Basic research into the origins of the design of the Kalashnikov rifle yields a popular story, oft-retold in Russian press releases when describing the most well-known name in military small arms worldwide. Young Mikhail, facing the Germans as a tank commander in WWII, caught shrapnel to his head in a one-sided battle with the Wehrmacht. When he woke up in the hospital he questioned why, when he and his comrades were competing for the use of one tired Mosin-Nagant bolt action rifle, his German foes were each armed with automatic weapons? His mind immediately began to work out a way to arm the Red Army with a weapon that would serve as a force-multiplier, making it much more difficult for a foreign body to invade with the ease of the initial Nazi blitzkrieg.

He built his weapon relatively quickly, but it was tested in the sour battles of the Cold War Era rather than in the crucible of the Second World War. Mikhail was still pleased. His weapon, he felt, would be a deterrent that would allow the Soviet Union to protect its basic infantrymen, allowing them to be the best armed fighting force in the world. The proxy battles of the Cold War would eliminate this dream in short order. Though there was initial reluctance to share the design, Soviet satellite states and, shortly thereafter, Communist allies were all armed with the AK-47. More importantly, they were armed with the ability to mass-produce the weapon, often funded directly by the USSR and supplied with the factory materials necessary for initial production. As those relationships also began to break down, Kalashnikov had to watch as his rifle, designed as a means of shielding Russian soldiers from harm, was used against them time and again.

A Colombian police officer guards Chinese-made AK-47 replicas seized on Nov. 18, 2009 (Image courtesy of NPR)

This was not the only way in which Kalashnikov’s beloved motherland slighted the inventor of its primary weapons platform. Though Kalashnikov designed and built the AK-47 largely on his own he never held any rights to the weapon. This was not a particularly large issue at the time of invention as he was given a relatively generous stipend and housing near his arms factory. As time went on, and particularly with the dissolution of the USSR, such support became much less substantial. Kalashnikov was able to weather this as well, though not without some feelings of resentment. The situation came to a head when the Yeltsin government, in a token show of praise, sent Kalashnikov a rusted pistol as a means of recognition. It was a slight that would color his view of the new Russian Federation for the rest of his life, as a regime that spawned little but economic corruption and hooliganism among Russia’s youth.

In 2003, Kalashnikov partnered with a British firm to lend his name to a collection of “manly” products ranging from umbrellas to pen knives. Of course, there was also a Kalashnikov vodka. It bore both his name and his image, and advertisements featured the proud general in full military regalia encouraging the buzz-seeking masses to drink up. These marketing contracts supplemented his stipend enough to allow him to continue living out the rest of his days in his modest housing near Izhevsk.

In his latter years Kalashnikov still very much liked to tinker, and to reflect on his most popular invention. Though he denied any responsibility for what he described as the misuse of his weapon, he did come to express some regret for what it had become: a symbol and weapon of choice for terrorists and revolutionary groups the world over. In a popular interview with The Guardian, Kalashnikov stated, “I would prefer to have invented a machine that people could use and that would help farmers with their work – for example a lawnmower.” His death deprived the world of the production of the Kalashnikov lawn mower. The inventor with an equal passion for his homeland and for mechanical tinkering will be forever inextricably linked with the rifle that bears his name.

Photo Credits:

Mikhail Kalashnikov as a young man (Image courtesy of Recoil)

A Colombian police officer guards Chinese-made AK-47 replicas seized on Nov. 18, 2009 (Image courtesy of NPR)

Kalashnikov posing with his invention, the AK-47 (Image courtesy of Recoil)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

***

Stephen Panico is a December 2011 graduate of The University of Texas at Austin with a degree Plan II Honors and History. He is currently Marketing Specialist at Austin tech company Apptive and plans to pursue his MBA in the near future.

Further Reading: