Anyone interested in early sound recordings can find a treasure trove at the Library of Congress website.

“In the Baggage Coach Ahead” is a great example of the sentimental ballads that became popular in the United States during the 1890s. The classic ballads were maudlin tearjerkers, narrative tales of lost love or dead mothers designed to pull at the heartstrings. They featured snappy melodies that lodged themselves in the heads of anyone within earshot. New York sheet music publishers churned them out by the score, hoping that a few would prove popular with theater audiences and the legions of young women who played the latest hits at the family piano. The assembly-line composition process marked the industrialization of American popular music.

Listen to “In the Baggage Coach Ahead”

“In the Baggage Coach Ahead” from 1896 hits all the requisite stops. The song takes place on the sleeping car on a train, where an inconsolable baby cries in its father’s arms. Other passengers demand silence, complaining that they cannot sleep. One woman then suggests that the father take the baby to its mother, a request that set up the song’s kicker. “I wish I could,” the father replies, “but she’s dead in the coach ahead.”

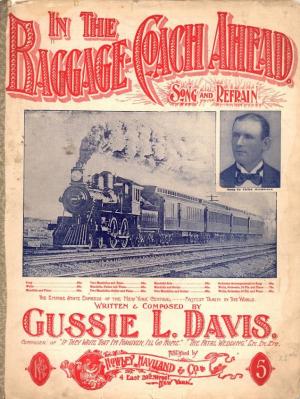

The song was the most popular composition of Gussie L. Davis, a pioneer in breaking down segregation in the music business. He was one of a very few African American songwriters who successfully published sentimental ballads during the decade. Most black writers were either barred from the industry or constrained to writing comic minstrel songs about black inferiority.

The song was the most popular composition of Gussie L. Davis, a pioneer in breaking down segregation in the music business. He was one of a very few African American songwriters who successfully published sentimental ballads during the decade. Most black writers were either barred from the industry or constrained to writing comic minstrel songs about black inferiority.

The performer, Vernon Dalhart, was a struggling opera singer who moved from Texas to New York around 1911. He eventually became a popular recording artist for the Edison phonograph company, waxing everything from light opera and minstrel songs to popular hits of the day.  In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with “The Prisoner’s Song,” often touted as the first country record to sell a million copies.

In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with “The Prisoner’s Song,” often touted as the first country record to sell a million copies.

Sentimental ballads such as “In the Baggage Coach Ahead” were popular, in part, because they could help Americans grapple with the dramatic social changes they were experiencing. Urbanization, industrialization, immigration, the expansion of railroad travel, and the availability of thousands of new consumer goods (including phonographs and commercial theater) brought increasing contact with people, products, and ideas from elsewhere. Sentimental ballads helped negotiate the intersection of public and private spheres. Davis’ last verse finds all the mothers and wives on the train helping the lone father sooth his crying child. It concludes, “Every one had a story to tell in their home of the baggage coach ahead.” Mothers saved the day and helped transform a public tragedy into a private morality lesson when witnesses shared the story with their loved ones back home.

Embracing “In the Baggage Coach Ahead” and its kin meant not having to choose between public and private allegiances. Sentimental ballads were commercial leisure that celebrated private domesticity. Listeners could identify with both by singing along with the odes to private virtue echoing from the public stage.

Karl H. Miller’s “Sounds of the Past #1” on Not Even Past

Sheet music cover: Historic American Sheet Music collection, Duke University Libraries Digital Collections

Portraits of Davis and Dalhart via Wikimedia Commons