By Karl Hagstrom Miller

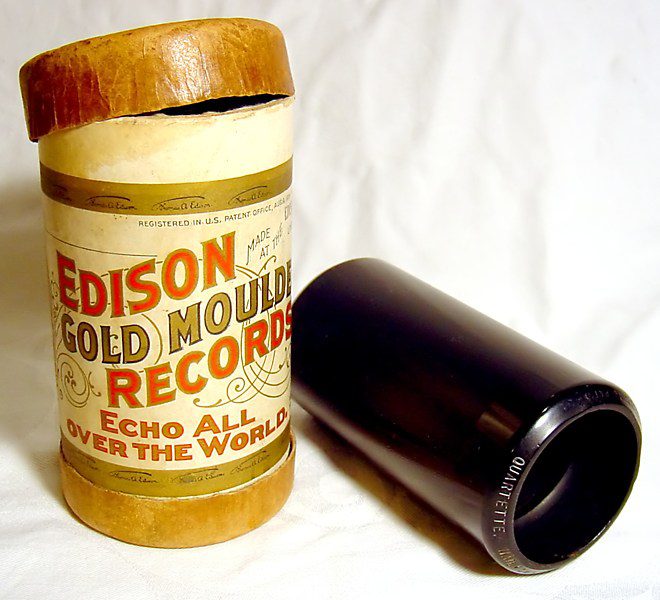

Interested in popular music and the music industry in the early twentieth century? The Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California at Santa Barbara has built perhaps the most useful archive on the planet for you.

Their website features a growing mountain of streaming and downloadable songs that were originally released on fragile cylinder recordings. To publicize the site and demonstrate its richness for both scholarship and teaching, this is the first in a series of posts that will feature cylinders I find particularly interesting or noteworthy.

Their website features a growing mountain of streaming and downloadable songs that were originally released on fragile cylinder recordings. To publicize the site and demonstrate its richness for both scholarship and teaching, this is the first in a series of posts that will feature cylinders I find particularly interesting or noteworthy.

First up is an early recording of one of the important ancestors of hillbilly music and humor.

LISTEN: Len Spencer, “The Arkansas Traveler,” Edison Ambersol 181 [1909]

“The Arkansas Traveler” was a fiddle tune and comedy skit that has been traced back to the 1840s. The tune itself long ago entered the traditional fiddle repertoire. It is one of the standards that beginners learn, virtuosi use to impress the judges at fiddle contests, and many kids know through its modern lyrics about smashing up a baby bumblebee. What is less well known is that the tune was part of an elaborate and ubiquitous comedy routine that addressed tensions between city and country.

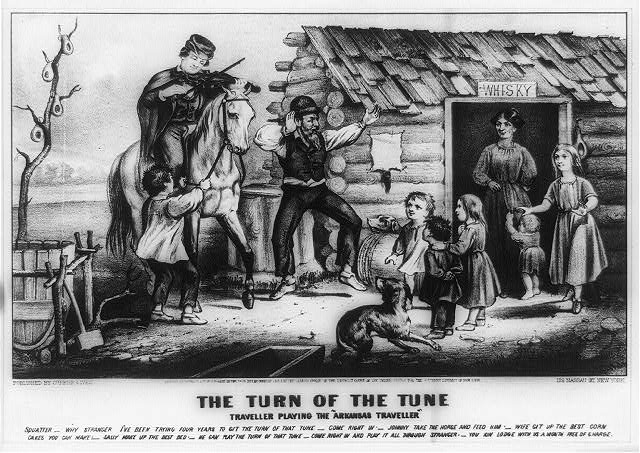

The skit portrayed a traveler (usually from the city or the East) coming across a squatter in rural Arkansas. As the squatter repeatedly saws the first strain of the tune on his fiddle, the two engage in pun-riddled banter. “Where does this road go?” the traveler asks. “It don’t go nowhere. Stays right where it is,” comes the reply. Tension grows as the traveler’s questions become more antagonistic and the squatter continues to dissemble. It is finally eased when the traveler grabs the fiddle and finishes the tune that the squatter had started. Laughter ensues, and the squatter welcomes the traveler to stay the night.

The humor of “The Arkansas Traveler” cut two ways. The rural fiddler’s apparent inability to comprehend the traveler’s questions pegged him as comically unsophisticated, reinforcing urban fantasies about the rural South. Yet it is easy to see the squatter’s naiveté as an act. He feigns ignorance in order to deflect the city’s slicker’s condescension, deflate his pretensions, and get him to leave. The traveler looks down on the backwoods primitive without realizing that the joke is on him.

Yet ultimately, “The Arkansas Traveler” tells a story of commonality rather than difference. In the skit, the tensions between the urban and rural characters dissolved as the two discover that they know the same music. The white hayseed and city slicker were not so different after all. White rural listeners thus could imagine holding their own in cities populated by the likes of the gullible yet ultimately endearing traveler, and their urban counterparts could identify with the fiddler, who may have expressed shared contempt for urban pretensions and represented the simplicity and straight-talk of their own real or imagined rural heritage.

“The Arkansas Traveler” provided the template for hillbilly humor from Fiddlin’ John Carson in the 1920s through the popular 1960s television show “Hee Haw” and Jeff Foxworthy’s “You might be a redneck if…” bit in the 21st century. It also demonstrated the market value of simultaneously promoting poor, white, rural southerners as both unprepared for participation in civilized society and the smartest ones in the room.

More NEP articles on the US South:

Civil War Savannah by Jacqueline Jones

Classic Books on the Civil War by George Forgie

Let the Enslaved Testify by Daina Berry

Photo credits:

Edison Gold Moulded Cylinder Record, ca. 1904 Released under the GNU Free documentation License

“The Turn of the Tune,” by John Cameron, Currier and Ives, c1870, CC ATribution Share-Alike 3.0