by Marc Palen

As we remember the tenth anniversary of the 9-11 attacks, we should also not forget that this year marks the 150th anniversary of the beginning of another tragic episode: this country’s Civil War that left more than 600,000 dead in its wake.

A torrent of controversy has in fact arisen alongside the Civil War’s sesquicentennial, the most prevalent being debates over the war’s causation.  Perhaps it is to be expected. Ever since the conflict’s inception, scholars have hotly debated whether, for example, the crisis was precipitated by Southern economic backwardness or Northern economic nationalism; the institution of slavery itself or its possible territorial expansion; a conspiracy of the “Slave Power” or a conspiracy of Northern manufacturers seeking to exploit the agrarian South.

Perhaps it is to be expected. Ever since the conflict’s inception, scholars have hotly debated whether, for example, the crisis was precipitated by Southern economic backwardness or Northern economic nationalism; the institution of slavery itself or its possible territorial expansion; a conspiracy of the “Slave Power” or a conspiracy of Northern manufacturers seeking to exploit the agrarian South.

Earlier this year, Time ran a story on the prevailing view of the Civil War’s causation among leading academics. In it, James McPherson stated that “everything stemmed from the slavery issue,” and David Blight finished off the article with the conclusion that “slavery was the cause of the war.” Similar unicausal sentiments have since popped up elsewhere. With such strong declarations coming from such preeminent scholars of the subject and the era, it would appear that the debate has been settled.

Well, not quite. While this line of argument has certainly become the mainstream, in recent years the Civil War’s economic complexities have garnered renewed scholarly attention. Economic issues may not have outweighed the broader issue of slavery as the primary causal factor of secession and war, but, scholars have recently sought to show how the oft-overlooked international political economy influenced other causes, including slavery.

Complexity is Not a Lost Cause

Stemming from the common trend toward boiling down such a complex story, the age-old tariff argument has once again arisen. This, in large part, is thanks to the heavy-handed treatment of the subject by James W. Loewen, author of the popular Lies my Teacher Told Me. In a widely read February Washington Post piece entitled “Five Myths About why the South Seceded,” he has provocatively suggested that “tariffs were not an issue in 1860, and Southern states said nothing about them.” In response to such a bold claim, policy historian Phil Magness has offered a nuanced rejoinder, taking interested readers through the contentious tariff issue in the years leading to Southern secession, focusing in particular upon the very real debate over the tariff in 1860 as the high Morrill Tariff bill haltingly made its way through Congress. He reminds us that the tariff was indeed a prominent issue on the eve of the Civil War.

Magness is not alone in recovering the economic remnants of Civil War history. Marc Egnal has made a particularly loud splash with Clash of Extremes: The Economic Origins of the Civil War (2009). In it, he preemptively refutes Loewen’s statement, suggesting instead that in the 1860 election the tariff was “the most important economic issue.” More importantly, he argues that slavery alone as a moral issue “didn’t explain why the sections clashed,” and that the oversimplified “slavery” mantra was therefore “fraught with problems.” By concluding that “economics more than high moral concerns produced the Civil War,” he revives and updates the interpretation first put forth by Charles and Mary Beard that the war was at heart an economic and ideological conflict between the growing protectionist Northeastern manufacturing section and the free-trading agrarians of the South. Egnal suggests that this sectional divide was made larger as the Western states—for so long siding with the South on most political matters—began developing their own infant industrial manufactures and found their interests aligning more and more with the North. The rise of the “Great Lakes economy” became further entwined with Northern markets alongside the rapid development of rail lines and canals. Egnal does not deny that the Republican Party contained strong antislavery roots, but he does suggest that such sentiment was overshadowed by the party’s adherence to the Homestead Act, internal improvements, and economic nationalism.

Magness is not alone in recovering the economic remnants of Civil War history. Marc Egnal has made a particularly loud splash with Clash of Extremes: The Economic Origins of the Civil War (2009). In it, he preemptively refutes Loewen’s statement, suggesting instead that in the 1860 election the tariff was “the most important economic issue.” More importantly, he argues that slavery alone as a moral issue “didn’t explain why the sections clashed,” and that the oversimplified “slavery” mantra was therefore “fraught with problems.” By concluding that “economics more than high moral concerns produced the Civil War,” he revives and updates the interpretation first put forth by Charles and Mary Beard that the war was at heart an economic and ideological conflict between the growing protectionist Northeastern manufacturing section and the free-trading agrarians of the South. Egnal suggests that this sectional divide was made larger as the Western states—for so long siding with the South on most political matters—began developing their own infant industrial manufactures and found their interests aligning more and more with the North. The rise of the “Great Lakes economy” became further entwined with Northern markets alongside the rapid development of rail lines and canals. Egnal does not deny that the Republican Party contained strong antislavery roots, but he does suggest that such sentiment was overshadowed by the party’s adherence to the Homestead Act, internal improvements, and economic nationalism.

Egnal’s interpretation has in turn led to a heated debate between himself and John Ashworth on H-CivWar, among others. With Ashworth calling conservative historian Charles Beard a “vulgar Marxist,” and charging Egnal as being “self contradictory” and suggesting that he minimizes the role of the millions of blacks at the war’s outbreak, both sides of the debate are worth reading.

Books on the Civil War’s political economic complexity continue to proliferate. In similar economically oriented fashion, John Majewski’s Modernizing a Slave Economy: The Economic Vision of the Confederate Nation (2009) stresses the importance of the South’s burgeoning manufacturing sector, the development of state-sponsored internal improvements and centralized economic regulations, and the corresponding growth of protectionist sentiment, demonstrating that the Confederacy was by no means united behind the twin banners of states’ rights and free trade. My own forthcoming work in the Journal of the Civil War Era in turn examines the Morrill Tariff’s transatlantic traction, particularly how it both garnered anti-Union sentiment and Confederate sympathy within free-trading Great Britain. Nicholas and Peter Onuf in Nations, Markets, and War: Modern History and the American Civil War (2006) also spend some time on exploring the Civil War’s economic intellectual roots, and Brian Schoen’s The Fragile Fabric of Union: Cotton, Federal Politics, and the Global Origins of the Civil War (2009) does a particularly fine job of reexamining the international political economy and Southern political thought from the 1780s to the conflict’s onset.

None of these historians discounts the importance of slavery, but they each demonstrate that such a stand-alone descriptor proves inadequate. The influence of slave uprisings, abolitionism, and free soil certainly deserves center stage, but the above projects should remind historians not to lose sight of the international political economic backdrop along the way. Remembering the Civil War’s complexities is not a lost cause.

You may also like:

Jacqueline Jones on Civil War Savannah

George Forgie on Civil War classics

Daina Berry on former-slave narratives

Photo Credits

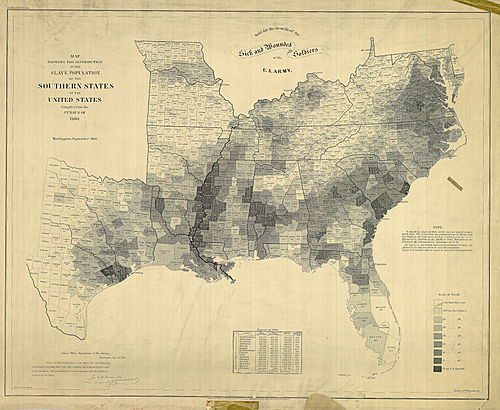

Map of percentage of slaves in the population in each county in the slave-holding states of the United States in 1860. By United States Coast Guard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Richmond Virginia, Woolen Factories and Pontoon Bridge, Civil War Photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress